“Good God!” said her ladyship faintly. A flash of anger came into her eyes. “How dare you come to me?” she said. “I vow it passes all bounds! I shall certainly not direct you where you may find him, and I marvel that you should expect it of me.”

Mrs. Challoner took a firm hold on her reticule, and said with determination: “Either the Duke or her grace the Duchess I must see and will see.”

Lady Fanny’s bosom swelled. “You shall never carry your horrid tales to the Duchess, I promise you. I make no doubt at all it’s a pack of lies, but if you think to make mischief with my sister, let me tell you that I’ll not permit it”

“And let me assure you, ma’am, that if you try to prevent me seeing the Duke you will be monstrous sorry for it. Your ladyship need not suppose that I shall keep my mouth shut. If I do not obtain his grace’s direction from you I’ll make an open scandal of it, and so I warn you!”

Lady Fanny curled her lip disdainfully. “Pray do so, my good woman. Really, I find you absurd. Even were his grace ten years younger, I for one should never believe such a nonsensical story.”

Mrs. Challoner felt more than ever that she had strayed into a madhouse. “What has his grace’s age to do with it?” she said, greatly perplexed.

“Everything, I imagine,” replied Lady Fanny dryly.

“It has nothing at all to do with it!” said Mrs. Challoner, growing more and more heated. “You may think to fob me off, ma’am, but I appeal to you as a mother. Yes, your la’ship may well start. It is as a mother, a mother of a daughter that I stand here to-day.”

“Oh, I don’t believe it!” cried Fanny. “Where are my lavender-drops? My poor, poor Léonie! Say what you have to: I shall not credit one word of it. And if you think to foist your odious daughter on to Avon, you make a great mistake! You should have thought of it before. I suppose the girl must be at least fifteen years of age.”

Mrs. Challoner blinked at her. “Fifteen years, ma’am? She’s twenty! And as for foisting her on to the Duke, if he has a shred of proper feeling he will make the best of it — though I am far from admitting her to be unworthy of the very highest honours — and accept her as a daughter (and, indeed, she is a sweet, dutiful girl, ma’am, and reared in a most select seminary) without any demur.”

“My good woman,” said Fanny pityingly, “if you imagine that Avon will do anything of the kind you must be a great fool. He has no proper feelings, as you choose to term them, at all, and if he paid for the girl’s education (which I presume he must have done) I am amazed at it, and you may consider yourself fortunate.”

“Paid for her education?” gasped Mrs. Challoner. “He’s never set eyes on her! What in the name of Heaven is your la’ship’s meaning?”

Fanny looked at her narrowly for a moment. Mrs. Challoner’s bewilderment was writ large on her face. Fanny pointed to a chair. “Be seated, if you please,” she said. Mrs. Challoner sat down thankfully. “And now perhaps you will tell me in plain words what it is you want,” her ladyship continued. “Is this girl Avon’s child, or is she not?”

Mrs. Challoner took nearly a full minute to grasp the meaning of this question. When she had realized its import she bounced out of her chair again, and cried: “No, ma’am, she is not! And I’ll thank your la’ship to remember that I’m a respectable woman even if I wasn’t thought good enough for Mr. Challoner. He married me for all he came of such high and mighty folk, and I’ll see to it that his grace of Avon’s precious son marries my poor girl!”

Lady Fanny’s rigidity left her. “Vidal!” she said with a gasp of relief. “Good God, is that all?”

Mrs. Challoner was still fuming with indignation. She glared at Fanny, and said angrily: “All, ma’am? All? Do you call it nothing that your wicked nephew has abducted my daughter?”

Fanny waved her back to her chair. “You have all my sympathies, ma’am, I assure you. But your errand to my brother is quite useless. He will certainly not be moved to urge his son to marry your daughter.”

“Will he not then?” cried Mrs. Challoner. “I fancy he will be glad to buy my silence so cheaply.”

Fanny smiled. “I must point out to you, my good woman, that it is your daughter and not my nephew that would be hurt by this story becoming known. You used the word ‘abduct’; I know a vast deal to Vidal’s discredit, but I never yet heard that he was in the habit of carrying off unwilling females. I presume your daughter knew what she was about, and I can only advise you, for your own sake, to bear a still tongue in your head.”

This unexpected attitude on the part of her ladyship compelled Mrs. Challoner to play her trump card earlier than she had intended. “Indeed, my lady? You are very much in the wrong, let me tell you, and if you imagine my daughter is without powerful relatives, I can speedily undeceive you. Mary’s grandpapa is none other than a general in the army, and a baronet. He is Sir Giles Challoner, and he will know how to protect my poor girl’s honour.”

Fanny raised her brows superciliously, but this piece of information had startled her. “I hope Sir Giles is proud of his grandchild,” she said languidly.

Mrs. Challoner, a spot of colour on either cheek-bone, hunted with trembling fingers in her reticule. She pulled out Mary’s letter, and threw it down on the table before her ladyship. “Read that, ma’am!” she said in tragic accents.

Lady Fanny picked the letter up, and calmly perused it. She then laid it down again. “I have not a notion what it is about,” she remarked. “Pray who may ‘Sophia’ be?”

“My younger daughter, ma’am. His lordship designed to run off with her, for he dotes madly on her. He sent her word to be ready to elope with him two nights ago, and Mary opened the letter. She is none of your frippery good-for-nothing misses, my lady, but an honest girl, and quite her grandpapa’s favourite. She meant, as you have seen, to save her sister from ruin. Ma’am, she has been gone two days, and I say that the Marquis has abducted her, for I know Mary, and I’ll be bound she never went with him willingly.”

Lady Fanny heard her in dismayed silence. The affair seemed certainly very serious. Sir Giles Challoner was known to her, and she felt sure that if this girl were in truth his grandchild he would not permit her abduction to pass unnoticed. A quite appalling scandal (if it did not turn out to be worse than a mere scandal) seemed to be brewing, and however waspishly Lady Fanny might have predicted that her nephew would in the end create such a scandal, she was not the woman to sit by and do nothing to prevent it. She had a soft corner for Vidal, and a very real affection for his mother. She had also her fair share of family pride, and her first thought was to apprise Avon instantly of this disastrous occurrence. Then her heart failed her. This was no tale to pour into Avon’s ears, at the very moment when his son had been obliged to leave the country for yet another offence. She had no clear idea of what the outcome of it all would be, or whether it would be possible to hush the matter up, but she determined to send word to Léonie.

She cast an appraising glance at Mrs. Challoner. She was a shrewd woman, and Mrs. Challoner would have been startled had she known how much that she had kept to herself Lady Fanny had guessed.

“I’ll do what I can for you,” Fanny said abruptly. “But you will do well to say nothing of this disagreeable matter to anyone. I shall repeat your very extraordinary story to my sister-in-law. Let me point out to you, ma’am, that if you raise a scandal you will lose the object you have in view. Once your daughter’s name is being bandied from lip to lip I can assure you my nephew won’t marry her. As to scandals, ma’am, I leave it to you to decide who will be most hurt by one.”

Mrs. Challoner hardly knew what to reply. Lady Fanny’s manner awed her; she was uncertain of her ground, for she had expected Lady Fanny to be horrified and alarmed. But Lady Fanny was so calm, so delicately scornful that she began to wonder whether she would be able to frighten the Alastairs with the threat of exposure after all. She wished she had her brother by, to advise her. She said rather pugnaciously: “And if I do keep silent? What then?”

Lady Fanny lifted her eyebrows. “I cannot take it upon myself to answer for my brother. I have informed you that I will tell my sister-in-law your story. If you will have the goodness to leave your address, no doubt the Duchess — or the Duke — will visit you.” She stretched out her hand towards a little silver bell, and rang it. “I can only assure you, ma’am, that if wrong has been done his grace will certainly arrange matters honourably. Permit me to bid you good-day.” She nodded dismissal, and Mrs. Challoner found herself rising instinctively from her seat.

The footman was holding the door for her to pass through. She said: “If I do not hear within a day, I shall act as I think best, my lady.”

“There is not the smallest chance that you will hear within the day,” said her ladyship coldly. “My sister is at the moment quite remote from London. You might perhaps hear in three or four days.”

“Well ...” Mrs. Challoner stood hesitating. The interview had not been conducted as she had planned. “I shall wait on you again the day after to-morrow, ma’am. And you need not think I’m to be fobbed off.” She moved towards the door, but paused before she had reached it, and remembered to give Lady Fanny her direction. She then curtsied and withdrew, feeling a little discomfited and considerably annoyed.

Had she been able to transport herself back into the house five minutes later she would have been somewhat comforted. No sooner had the front door closed behind her than Lady Fanny flew up out of her chair, violently rang her hand-bell, and, upon the footman’s return, sent him to find Mr. John Marling at once.

Mr. Marling entered the room presently to find his mamma in a distracted mood.

“Good heavens, John, what an age you have been!” she cried. “Pray shut the door! The most dreadful thing has happened, and you must go immediately to Bedford.”

Mr. Marling replied reasonably: “I fear it will be most inconvenient for me to leave London to-day, mamma, as I am invited by Mr. Hope to accompany him to a meeting of the Royal Society. I understand there will be a discussion on the Phlogistic Theory, in which I am interested.”

Lady Fanny stamped her foot. “Pray what is the use of a stupid theory when Vidal is about to shame us all with a dreadful scandal? You can’t go to any society! You must go to Bedford.”

“When you ask, mamma, what is the use of the Phlogistic Theory, and apparently compare it with Vidal’s exploits, I can only reply that the comparison is ridiculous, and renders the behaviour of my cousin completely insignificant,” said Mr. Marling with heavy sarcasm.

“I do not want to hear another word about your tiresome theory,” declared her ladyship. “When our name is dragged in the mud we shall see whether Vidal’s conduct is insignificant or no.”

“I am thankful to say, ma’am, that my name is not Alastair. What has Vidal done now?”

“The most appalling thing! I must write at once to your aunt. I always said he would go too far one of these days. Poor, poor Léonie! I vow my heart quite aches for her.”

Mr. Marling watched her seat herself at her writing-table, and once more inquired: “What has Vidal done now?”

“He has abducted an innocent girl — not that I believe a word of it, for the mother’s a harpy, and I’ve little doubt the girl went with him willingly enough. If she didn’t, I shudder to think what may happen.”

“If you could contrive to be more coherent, mamma, I might understand better.”

Lady Fanny’s quill spluttered across the paper. “You will never understand anything except your odious theories, John,” she said crossly, but she paused in her letter-writing, and gave him a vivid and animated account of her interview with Mrs. Challoner.

At the end of it, Mr. Marling said in a disgusted voice: “Vidal is shameless. He had better marry this young female and live abroad. I quite despair of him, and I feel sure that while he is allowed to run wild in England we shall none of us know a moment’s peace.”

“Marry her? And pray what do you suppose Avon would have to say to that? We can only hope and trust that something may yet be done.”

“I had better journey to Newmarket, I suppose, and inform my uncle,” said Mr. Marling gloomily.

“Oh John, don’t be so provoking!” cried his mother. “Léonie would never forgive me if I let this come to Avon’s ears. You must fetch her from the Vanes at once, and we will lay our heads together.”

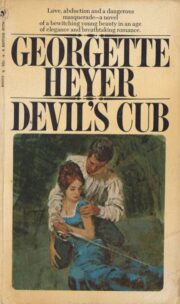

"Devil’s Cub" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Devil’s Cub". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Devil’s Cub" друзьям в соцсетях.