“If Baby J should be ill, or you yourself sick, then there is no one there who would care for you,” he said in the last days of August, while he planned and packed his clothes for the journey.

“There’s no one here in Meopham who would care for me,” she said inaccurately.

“Your whole family is here, cousins, sisters, aunts and your mother.”

“I can’t see Gertrude wasting much time on my comfort!”

John nodded. “Maybe not. But she would do her duty by you. She would make sure that you had a fire and water and food. Whereas at Hatfield I know no one but the workmen. Not even the house staff are fully at work yet. The place is still half-built.”

“They must be finished soon!”

John was incapable of explaining the scale of the project. “It looks as if they could build for a dozen years and never be done!” he said. “They have the roof on now, at least, and the walls complete. But all the inside fittings, the floors, the windows, there is all that to do. And the paneling is yet to come; there are hundreds of carpenters and woodcarvers on site! I tell you, Elizabeth, he is building a little town there, in the middle of a hundred meadows. And I must plant the meadows and turn them into a great garden!”

“Don’t sound so overawed!” Elizabeth said affectionately. “You know you are as excited as a child!”

John smiled, acknowledging the truth. “But I fear for him,” he confided. “It is a great task he has taken on. I can’t see how he can bear the cost of it. And he is buying property in London too, and then selling it on. I fear he will overstretch himself and if he gets into debt-” He broke off. Not even to Elizabeth would he trust the details of Cecil’s business arrangements, the bribes routinely taken, the Treasury money diverted, the men bankrupted by the king one day on charges of treason or offenses against the Crown whose estates were bought up by his first minister at knockdown prices the next.

“They say he is an engrosser,” Elizabeth remarked. “Not a wood or a common is safe from his fences. He takes it all to himself.”

“It is his own,” John said stoutly. “He takes what is his by right. Only the king is above him, and God above him.”

Elizabeth gave him a skeptical look but kept her thoughts to herself. She was too much like her father – a clergyman of stoutly independent Protestantism – to accept John’s spiritual hierarchy which led from God in heaven down to the poorest pauper with each man in his place, and the king and the earl a small step down from the angels.

“I fear for myself too,” John said. “He has given me a purse of gold and ordered me to buy and buy. I am afraid of being cheated, and I am afraid of shipping these plants so far. He wants a garden all at once, so I should buy plants as large and fruitful as I can get. But I am sure that little sturdy ones might travel better!”

“There’s no one in the kingdom better able than you,” Elizabeth said encouragingly. “And he knows it. I just wish I might come with you. Are you not afraid to go alone?”

John shook his head. “I’ve longed to travel ever since I was a boy,” he said. “And my work for my lord has tempted me every time I go down to the docks and speak to the men who have sailed far overseas. The things they have seen! And they can bring back only the tiniest part of it. If I might go to India with them or even Turkey, just think what rarities I might bring home.”

She watched him, frowning slightly. “You would not want to go so far, surely?”

John put his arm around her waist to reassure her, but could not bring himself to lie. “We are a nation of travelers,” he said. “The finest of the lords, my lord’s friends, are all men who seek their fortunes over the seas, who see the seas as their highway. My lord himself invests in every other voyage out of London. We are too great a nation with too many people to be kept to the one island.”

Elizabeth was a woman from a village that counted the men who were lost to the sea, and tried to keep them on the land. “You don’t think of leaving England?”

“Oh, no,” John said. “But I don’t fear to travel.”

“I don’t know how you can bear to leave us for so long!” she complained. “And Baby J will be so changed by the time you come back.”

John nodded. “You must note down every new thing he says so that you can remember to tell me when I return,” he said. “And let him plant those cuttings I brought for him. They are his lordship’s favorite pinks, and they smell very sweet. They should grow well here. Let him dig the hole himself and set them in; I showed him how to do it this afternoon.”

“I know.” Elizabeth had watched from the window as her husband and her quick dark-eyed dark-haired son had kneeled side by side by the little plot of earth and dug together, John straining to understand the rapid babble of baby talk, Baby J looking up into his father’s face and repeating the sound until between guesswork and faith they could understand each other.

“Dig!” Baby J insisted, thrusting a little trowel into the earth.

“Dig,” his father agreed. “And now we put these little fellows into their beds.”

“Dig!” Baby J insisted again.

“Not here!” John said warningly. “They need to rest quiet here so that they can grow and make pretty flowers for Mama!”

“Dig! J want dig!”

“Not dig!” John replied, descending rapidly to equal stubbornness.

“Dig!”

“No!”

“Dig!”

“No! Elizabeth! Come and take your son out of this! He is going to destroy these before they even know they’ve been transplanted!”

She had come from the house and swept Baby J up, and taken him down to the end of the garden to pet Daddy’s horse.

“I don’t know that he will make a gardener,” she warned. “You should not count on it.”

“He understands the importance of deep digging,” John said firmly. “Everything else will follow.”

August 1610

John set sail in September, and experienced a rough and frightening crossing after waiting for four dull days off Gravesend for a southerly wind. He landed in Flushing and hired a large flat-bottomed canal boat so that he could stop at every farm and enquire what they had to sell, all the way down the canal to Delft. To his relief the canal boatman spoke English even though his accent was as strong as any Cornishman’s. The boat was drawn by an amiable sleepy horse which wandered along the tow path and grazed on the lush banks during John’s frequent halts. He found farmers of flowers whose whole trade consisted of nothing but the famous tulips, and whose whole fortune rested on being able to produce and then reproduce the new colors of blooms. There were farms like John had never seen before. Row upon row of floppy-leaved stalks were tended by women wearing huge wooden clogs against the rich sandy soil, and big white hats against the sun, working their way down the rows with an implement like a wooden spoon, gently lifting the smooth round bulbs from the ground and laying them softly down, and the cart coming along behind to gather them all up.

John watched them. Each set of leaves which had grown from one bulb now had a cluster of three, perhaps even four, bulbs at the end of their white stems. Most of them even carried fat buds at the head where the petals had been and when the women spotted them, and they never missed one however long he watched, they cut them off and popped them in their apron pockets. Where one valuable bulb had been set in the ground and flowered there were now four, and maybe three dozen seeds as well. A man could quadruple his investment in one year for no more labor than keeping the field free of weeds and digging up his capital in the autumn.

“Profitable business,” John remarked enviously under his breath, thinking of the price he paid for tulips in England.

At every canalside market town he had the boatman tie up and wait for him on board, sometimes for hours, sometimes for days, as he wandered around the market gardens and picked out a well-shaped tree, a sack of common bulbs, a purse full of seeds. Wherever he could, he bought in bulk, haunted by the thought of the rich green commonland and meadows around Hatfield waiting for forests and plantations and mazes and orchards. Wherever he could find someone who could speak English and had the appearance of an honorable man, he made a contract with him to send on more plants to England as they matured.

“A great planting scheme,” one of the Dutch farmers commented.

John smiled but his forehead was creased with worry. “The greatest,” he said.

Despite his rooted belief that Englishmen were the best of the world, and England undeniably the best country, John could not help but be impressed with the labor these people had put into their land. Each canal bank was maintained as smartly as each town doorstep. They took a pleasure and a pride in things being just so. And their rewards were towns which exuded wealth and a land which was interlaced with an efficient transport system that put the potholed roads of England to shame.

The dykes that held back the shifting sands and the high waves of the North Sea were a wonder to John, who had seen the feckless neglect of the marshes and waterlogged estuaries of the Fens and East Anglia. He had not thought it was possible to do anything with land soured by salt, but he saw the Dutch farmers had learned the way of it and were making use of land that an Englishman would call waste ground and abandon as hopeless. John thought of the harbors and inlets and boggy places all around the coast, even in land-hungry Kent and Essex, and how in England they were left to lie fallow, steeped in salt, whereas in Holland they were banked off from the sea and growing green.

He could not help but admire their labor and their skill, and he could not help but envy the Dutch prosperity. There was no hunger in the Holland Provinces, and basic fare was rich and good. They ate cheese on buttered bread, a double helping of richness and fat, and did not think twice about it. Their cows grazed knee-deep in lush wet pastureland and gave abundant milk. They were a people who saw themselves as divinely rewarded for their struggle against the papist Spanish, and John, idling down the narrow canals, looking left and right for plants and flowers tucked away in the moist grasses, had to agree that the Protestant God was a generous one to this, His favored people.

When they reached The Hague, Tradescant sent the loaded barge back with instructions to ship all the plants directly to England. He stood on the stone wharf and watched the swaying heads of trees glide slowly away. Some of the cherry trees were bearing fruit and he saw, with irritation, that once they were beyond hailing distance the bargee picked a handful and ate them, spitting the stones carelessly into the glassy water of the canal.

In Flanders he bought vines, and watched them pruned of their yellow leaves and thick black grapes in preparation for their journey. He ordered their roots to be wrapped in damp sacking and plunged into old wine casks for their voyage home. He sent a message ahead of them, in the careful script which Elizabeth had taught him, so that a gardener from Hatfield would meet them with a cart on the dockside, to take them back and heel them in the same day, without fail, making sure to water them religiously at dawn every day until Tradescant came home.

The Prince of Orange’s gardener admitted Tradescant to the beautiful garden behind the palace of The Hague and showed him around. It was a garden in the grand European style, with large stone colonnades and broad sweeping walks. Tradescant spoke to him of his work at Theobalds, planting between the box hedges and replacing the colored stones of the knot garden with lavender. The gardener nodded with enthusiasm and showed Tradescant his version of the changing style in a little garden at the side of the palace where he had used tidily pruned lavender for the hedges themselves. They made a softer pattern and had more variation of color than the usual box hedge. They did not harbor insects and when a woman passed by, her skirts brushed against the leaves and released a cloud of perfume. When he left, Tradescant had a trayful of rooted cuttings and a letter of introduction to the great physic garden at Leiden.

He traveled overland to Rotterdam, uncomfortable on a big broad-backed horse, all the way seeking out English-speaking farmers who could tell him about the growing of their precious tulips. In the darkened cellars of ale houses, drinking a rich sweet beer which was new to John, called “thick beer,” they swore that the new colors entered into the heart of the flowers by slicing into the very heart of the bulb.

“Does it not weaken them?” John asked.

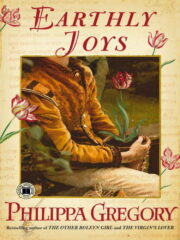

"Earthly Joys" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Earthly Joys". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Earthly Joys" друзьям в соцсетях.