John looked forward. It was true. The causeway was half underwater; he would be lucky, with his weak knee, to get to the other side. The lieutenant grabbed his arm. “Come on!”

The two men, clinging to each other for balance, pushed their way through the water to the other side, their feet unsteady on the wet wooden track. Every now and then a deeper wave threatened to wash them into the sea altogether. Once John lost his footing and only the other man’s grip saved him. They tumbled together onto the marshy wetland on the other side and ran toward where the Triumph’s landing craft were plying from the boggy shore to the ship.

John flung himself on board one of the craft and looked back as the boat took him from shore. It was impossible to tell friend from enemy; they were alike mud-smeared, knee-deep in water, stabbing and clawing for their own safety as the high dirty waves rolled in. The landing craft crashed abruptly against the side of the Triumph and John reached up to grip the nets hung over the side of the ship. The pressure of the men behind him pushed him up, his weaker leg scrabbling for a foothold but his arms heaving him upward. He fell over the ship’s side and lay on the deck, panting and sobbing, acutely aware of the blissful hardness of the holystoned wood of the deck under his cheek.

After a moment he pulled himself to his feet and went to where his lord was looking out to the island.

It was a massacre. Almost all the English soldiers behind John had been caught between the sea and the French. They had plunged off the causeway, or tried to escape by running through the treacherous marsh. The cries of the drowning men were like seagulls on a nesting site – loud, demanding, inhuman. Those bobbing in the water or trying to crawl back on to the causeway died quickly, under the French pikes. The French army, who were left dryshod on land before the causeway, had the leisure to reload and to fire easily and accurately into the marshes and the sea, where a few men were striking out for the ship. The front ranks, who had done deadly work off the submerged causeway, were falling back before the sea and stabbing at the bodies of Englishmen who were rolling and tumbling in the incoming waves.

The captain of the Triumph came to Buckingham as he stared, blank with horror, at his army drowning in blood and brine. “Shall we set sail?”

Buckingham did not hear him.

The captain turned to John. “Do we sail?”

John glanced around. He felt as if everything were underwater, as if he were underwater with the other Englishmen. He could hardly hear the captain speak, the man seemed to swim toward him and recede. He tightened his grip on the balustrade.

“Is another ship behind us to take off survivors?” he asked. His lips were numb and his voice was very faint.

“What survivors?” the captain demanded.

John looked again. His had been the last landing craft; the men left behind were rolling in the waves, drowned, or shot, or stabbed.

“Set sail,” John said. “And get my lord away from here.”

Not until the whole fleet was released from the grip of the treacherous mud and waves and was at sea did they count their losses and realize what the battle had cost them. Forty-nine English standards were missing, and four thousand English men and boys, unwillingly conscripted, were dead.

Buckingham kept to his cabin on the voyage home. It was said that he was sick, as so many of the men were sick. The whole of the Triumph was stinking with the smell of suppurating wounds, and loud with the groans of injured men. Buckingham’s personal servant took jail fever and weakened and died, and then the Lord High Admiral was left completely alone.

John Tradescant went down to the galley, where one cook was stirring a saucepan of stock over the fire. “Where is everyone?”

“You should know,” the man said sourly. “You were there as well as I. Drowned in the marshes, or skewered on a French pike.”

“I meant, where are the other cooks, and the servers?”

“Sick,” the man answered shortly.

“Put me up a tray for the Lord High Admiral,” John said.

“Where’s his cupbearer?”

“Dead.”

“And his server?”

“Jail fever.”

The cook nodded and laid a tray with a bowl of the stock, some stale bread and a small glass of wine.

“Is that all?” John asked.

The man met his eyes. “If he wants more he had better revictual the ship. It’s more than the rest of us will get. And most of his army is face down in the marshes eating mud and drinking brine.”

John flinched from the bitterness in the man’s face. “It wasn’t all his fault,” he said.

“Whose then?”

“He should have been reinforced; we should have sailed with better supplies.”

“We had a six-horse carriage and a harp,” the cook said spitefully. “What more did we need?”

John spoke gently. “Beware, my friend,” he said. “You are very near to treason.”

The man laughed mirthlessly. “If the Lord High Admiral has me executed before the mast there will be no dinner for those that can eat,” he said. “And I would thank him for the release. I lost my brother in Isle of Rue, I am sailing home to tell his wife that she has no husband, and to tell my mother that she has only one son. The Lord High Admiral can spare me that and I would thank him.”

“What did you call it?” John asked suddenly.

“What?”

“The island.”

The cook shrugged. “It’s what they all call it now. Not the Isle of Rhé; the Isle of Rue, because we rue the day we ever sailed with him, and he should rue the day he commanded us. And like the herb rue his service has a poisonous and bitter taste that you don’t forget.”

John took up the tray and went to Buckingham’s cabin without another word.

He was lying on his bunk on his back, one arm across his eyes, his pomander swinging from his fingers. He did not turn his head when Tradescant came in.

“I told you I want nothing,” he said.

“Matthew is sick,” John said steadily. “And I have brought you some broth.”

Buckingham did not even turn his head to look at him. “John, I want nothing, I said.”

John came a little closer and set the tray on a table by the bed. “You must eat something,” he urged, as gentle as a nurse with a child. “See? I have brought you a little wine.”

“If I drank a barrel I would not be drunk enough to forget.”

“I know,” John said steadily.

“Where are my officers?”

“Resting,” John said. He did not say the truth, that more than half of them were dead and the rest sick.

“And how are my men?”

“Low-spirited.”

“Do they blame me?”

“Of course not!” John lied. “It is the fortune of war, my lord. Everyone knows a battle can go either way. If we had been reinforced…”

Buckingham raised himself on an elbow. “Yes,” he said with sudden vivacity. “I keep doing that too. I keep saying: if we had been reinforced, or if the wind had not gotten up that night in September, or if I had accepted Torres’s terms of surrender the night that I had them, or if the Rochellois had fought for us… if the ladders had been longer or the causeway wider… I go back and back and back to the summer, trying to see where it went wrong. Where I went wrong.”

“You didn’t go wrong,” John said gently. He sat, unbidden, on the edge of Buckingham’s bed and passed him the glass of wine. “You did the best you could, every day you did your best. Remember that first landing when you were rowed up and down through the landing craft and the French turned and fled?”

Buckingham smiled, as an old man will smile at a childhood memory. “Yes. That was a day!”

“And when we pushed them back and back and back into the citadel?”

“Yes.”

John passed him the bowl of soup and the spoon. Buckingham’s hand trembled so much that he could not lift it to his mouth. John took it and spooned it for him. Buckingham opened his mouth like an obedient child, John was reminded of J as a baby tucked into his arm, seated on his lap, feeding from a bowl of gruel.

“You will be glad to see your wife again,” he said. “At least we have come safe home.”

“Kate would be glad to see me,” Buckingham said. “Even if I had been defeated twenty times over.”

Almost all the soup had gone. John broke up the dried bread into pieces, squashed them into the dregs and then spooned them into his master’s mouth. Some color had come into the duke’s face but his eyes were still dark-ringed and languid.

“I wish we could go on sailing and never get home at all,” he said slowly. “I don’t want to get home.”

John thought of the little fire in the galley and the shortage of food, of the smell of the injured men and the continual splash of bodies over the side in one makeshift funeral after another.

“We will make port in November, and you will be with your children for Christmas.”

Buckingham turned his face to the wall. “There will be many children without fathers this Christmas,” he said. “They will be cursing my name in cold beds up and down the land.”

John put the tray to one side and put his hand on the younger man’s shoulder. “These are the pains of high office,” he said steadily. “And you have enjoyed the pleasures.”

Buckingham hesitated, and then nodded. “Yes, I have. You are right to remind me. I have had great wealth showered on me and mine.”

There was a little silence. “And you?” Buckingham asked. “Will your wife and son welcome you with open arms?”

“She was angry when I left,” John said. “But I will be forgiven. She likes me to be home, working in your garden. She has never liked me traveling.”

“And you have brought a plant back with you?” Buckingham asked sleepily, like a child being entertained at bedtime.

“Two,” John said. “One is a sort of gillyflower and the other a wormwood, I think. And I have the seeds of a very scarlet poppy which may take for me.”

Buckingham nodded. “It’s odd to think of the island without us, just as it was when we arrived,” he said. “D’you remember those great fields of scarlet poppies?”

John closed his eyes briefly, remembering the bobbing heads of papery red flowers which made a haze of scarlet over the land. “Yes. A bright brave flower, like hopeful troops.”

“Don’t go,” Buckingham said. “Stay with me.”

John went to sit in the chair but Buckingham, without looking, put out his hand and pulled John down to the pillow beside him. John lay on his back, put his hands behind his head and watched the gilded ceiling rise and fall as the Triumph made her way through the waves.

“I am cold in my heart,” Buckingham said softly. “Icy. Is my heart broken, d’you think, John?”

Without thinking what he was doing, John reached out and gathered Buckingham so that the dark tumbled head rested on his shoulder. “No,” he said gently. “It will mend.”

Buckingham turned in his embrace and put his arms around him. “Sleep with me tonight,” he said. “I have been as lonely as a king.”

John moved a little closer and Buckingham settled himself for sleep. “I’ll stay,” John said softly. “Whatever you want.”

The horn lantern swung on its hook, throwing gentle shadows across the gilded ceiling as the boat heaved and dropped in gentle waters. There was no sound from the deck above them. The night watch was quiet, in mourning. John had a sudden strange fancy that they had all died on the Isle of Rue and that this was some afterlife, on Charon’s boat, and that he would travel forever, his arms around his master, carried by a dark tide into nothingness.

Sometime after midnight John stirred, thought for a moment he was at home and Elizabeth was in his arms, and then remembered where he was.

Buckingham slowly opened his eyes. “Oh, John,” he sighed. “I did not think I would ever sleep again.”

“Shall I go now?” Tradescant asked.

Buckingham smiled and closed his eyes again. “Stay,” he said. His face, gilded by the lamplight, was almost too beautiful to bear. The clear perfect profile and the sleepy languorous eyes, the warm mouth and the new sorrowful line between the arched brows. John put a hand out and touched it, as if a caress might melt that mark away. Buckingham took the hand and pressed it to his cheek, and then drew John down to the pillows. Gently, Buckingham raised himself up above him and slid warm hands underneath John’s shirt, untied the laces on his breeches. John lay, beyond thought, beyond awareness, unmoving beneath the touch of Buckingham’s hands.

Buckingham stroked him, sensually, smoothly, from throat to waist and then laid his cold, stone-cold face against John’s warm chest. His hand caressed John’s cock, stroked it with smooth confidence. John felt desire, unbidden, unexpected, rise up in him like the misplaced desire of a dream.

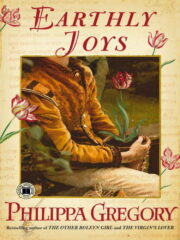

"Earthly Joys" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Earthly Joys". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Earthly Joys" друзьям в соцсетях.