“I’ll wait down here with you if I may,” John said. He looked around the shop, which was lined with small drawers, none of them marked. “It’s like a treasure chest.”

“John told me that the Duke of Buckingham has a room like this, but he stores curiosities,” she said. With a shock John realized that she did not call his son J, but John.

“Yes,” he said. “My lord has some very beautiful and curious things.”

“And you arrange them and collect them for him?”

“Yes.”

“You must have seen many marvels,” she said seriously.

John smiled at her. “And many falsehoods. Foolish forgeries cobbled together to try to catch the unwary.”

“All treasure is a trap for the unwary,” she observed.

“Indeed,” John said, disliking the tone of piety. “I shall buy something from you to take home to my wife. Do you have some pretty ribbons or lace for her to trim a collar?”

Jane bent below the counter and slid out a tray. She spread a little black velvet cloth so the lace was shown to its best advantage and laid out one piece, and then another, for him to see.

“And ribbons,” she said. They came from a dozen little drawers, arranged by color. She spread them before him, the cheap scratchy thin ones, and the lustrous silkier lengths.

“Are they not a trap to catch the unwary?” John asked, watching her absorbed face as she smoothed the lengths of ribbon before him, and folded them so that he could admire their shine.

She met his smile without embarrassment. “They are the hard work of good women,” she said. “They work to put bread in their mouths and we pay them a fair price and sell at a good profit. It is not just what you earn, but how you spend your money, that is judged on the great day. In this house we buy and sell fairly and nothing is wasted.”

“I’ll take that lace,” John decided. “Enough to make a collar.”

She nodded and cut him the measure he needed. “A shilling,” she said. “But you may have it for tenpence.”

“I’ll pay the full shilling,” he said. “For the good women.”

She gave a sudden, delicious gurgle of laughter, her whole face lighting up and her eyes dancing. “I’ll see that they get it,” she said.

She took his coin and put it away in a strongbox under the desk, entered the purchase in a ledger, and then wrapped the scrap of lace very carefully and tied it with a piece of wool. John stowed it in the deep pocket of his coat.

“Here’s Father,” Jane said.

John turned to greet the man. He looked incongruously more like a farmer than a seller of cloth and haberdashery. He was broad-shouldered and red-faced, well-dressed in sober black and gray and with a small lace collar. He held his hat in his hand and put out his other hand to John for a firm handshake.

“I am glad to meet you at last,” he said. “We have heard nothing from John but about his father’s travels since he first came here, and we prayed for you while you were in such peril off France.”

“I thank you,” John said, surprised.

“Daily, and by name,” Josiah Hurte went on. “He is a mighty all-wise, all-powerful God; but there is no harm in reminding him.”

John had to suppress a smile. “I suppose not.”

Josiah Hurte looked at his daughter. “Any sales?”

“Just a piece of lace to Mr. Tradescant, here.”

His tradesman’s instinct warred with his desire to be generous to John’s father. The desire for a small profit won. “Times are very hard for us,” he said simply.

John looked around the well-stocked shop.

“It doesn’t show yet,” Josiah said, following his gaze, “but every month things are getting tighter. We have a constant stream of requisitions from the king, fines for this, new taxes for that. And goods which were free to buy and sell suddenly become farmed out to courtiers as monopolies and we have to pay a fee to the monopoly holder. The king demands a free gift from his subjects and the vicar or the churchwardens come round to my shop, look at the outside, decide on their own what I can afford, and I face prison if I refuse.”

“The king has great expenses,” John said pacifically.

“My wife and my friends would spend all my money too if I let them,” the Puritan said shortly. “So I don’t let them.”

John said nothing.

“Forgive me,” the man said suddenly. “My daughter swore me to silence on this matter and I broach it the moment I am in the door!”

John could not resist a laugh. “My son too!”

“They feared we would quarrel but I would never come to blows over politics.”

“I have seen enough of warfare this year,” John agreed.

“It is a criminal shame, though,” Josiah continued, leading the way up the stairs from the shop. “My guild can no longer control the trade because the court favorites now run the market in thread and lace and silk, and so my apprentices are no longer guaranteed their work or their wages; other men come into the trade and force prices and wages down and up at their whim. I wish you would tell the duke that if the poor are to be fed and the widows and children safeguarded, we need a powerful guild and a steady trade. We cannot have changes every time a courtier needs a new place.”

“He does not take my advice,” John replied. “Indeed, I think he leaves the business of the city and trade to others.”

“Then he should not have taken the monopoly for gold and silver thread into his keeping,” the mercer said triumphantly. “If he cares nothing for trade then he should not engross it. He will ruin the trade and ruin himself, and ruin me.”

John nodded, uncertain how to answer, but his host slapped the side of his head with a broad palm. “Again!” he cried. “And promised Jane I would not. Not another word, Mr. Tradescant. So take a glass of wine with me?”

“Willingly.”

Dinner was a respectable affair preceded by a lengthy grace, but Mrs. Hurte laid a good table and her husband was generous with small ale and had a good wine. J sat beside Jane and spent the meal regarding her with a steady admiring gaze. John watched his son with a wry amusement.

The Hurtes were a pleasant straightforward couple. Mrs. Hurte presided over the puddings at her end of the table and Josiah Hurte carved the beef at his end. Between them sat their guests and Jane, and two apprentices.

“We dine in the old way,” Mr. Hurte confirmed, seeing John looking down the table. “I believe a man who takes an apprentice boy should bring him up as his own. He should feed his body as well as his mind.”

John nodded. “I have only ever had my son work for me,” he said. “My other gardeners are hired by my master.”

“Is the duke at New Hall now?” Mrs. Hurte asked.

Even in this quiet parlor the mention of his name hurt John like a twinge of pain from an unhealed wound.

“No, he is at court,” he said shortly. J directed a glance of unspoken appeal at him and Jane looked anxious.

“They are having great revelry this Christmas, now that the duke is safely returned,” Mrs. Hurte observed.

“I daresay,” said John.

“Shall you see him at Whitehall before you return to New Hall?”

“No,” John said. He had a pain now, as sharp as indigestion, under his ribs. He pushed his plate away, sated with grief. “I may not go to him unless he sends for me.”

He realized that the young woman, Jane Hurte, was looking at him and her face was full of sympathy, as if she understood a little of what he was feeling. “It must be a hard task to serve a great lord,” she said gently. “He must come and go like a planet in the sky and all you can do is watch and wait for him to come again.”

Her father bent his head and said softly: “I pray that we may all serve a greater master. Amen.”

But Jane did not take her eyes from John and her smile was steady.

“It is hard.” His voice was full of pain, even in his own ears. “But I have made my choice and I must serve him.”

“Keep us all in service to the Lord our God,” Josiah Hurte prayed again, and this time Jane Hurte, still watching John’s strained face, said: “Amen.”

The two young people were allowed out to walk together. Jane had some deliveries which had to be made, and J was to go with her to help with the basket. John thought that the sight of J carrying the basket as if it were made of glass and holding Jane by the arm as if she were a posy of flowers, mincing down the London street, was one he would never forget.

One of the apprentices walked behind them, bearing a stout stick.

“She has to be accompanied now,” Mrs. Hurte said. “There are so many beggars and many of them sickly. She cannot go out alone anymore.”

“J will take care of her,” John said reassuringly. “See how he holds her arm! And see him with that basket!”

“He’s a taking young man,” Josiah Hurte remarked pleasantly. “We like him.”

“He’s very much in love with your daughter,” John said. “Are you in favor of a match?”

The mercer hesitated. “Would he remain in the service of the duke?”

“I have some rented fields, and some land I bought on the advice of my old master, the earl. I have the fee for a Whitehall granary-”

“You are a garneter?” Josiah interrupted, surprised.

John had the grace to look embarrassed. “It is a sinecure. I don’t do the work but I have the pay for doing it.”

Josiah nodded. His daughter’s future father-in-law was benefiting from the very system he condemned: places and work given to men who knew nothing about the trade, who had no intention of learning, who subcontracted the task and kept the inflated pay.

“But our main work is in the duke’s gardens,” John continued smoothly. “The planning and planting of his gardens and the collection in his cabinet of rarities. J has served his apprenticeship under me and will follow me into the place at my death.”

“I would be unhappy at Jane joining the duke’s household,” the man said frankly. “His reputation is bad.”

“With women?” Tradescant shook his head. “My lord duke can have the pick of every lady at court. He does not trouble his servants.” He felt the pain beneath his ribs as he spoke. “He is a man very well loved. He does not need to buy his pleasure from his servants.”

“Could she practice her religion in your house, as she wishes?”

“Providing that she gives no offense to others,” John said. “My wife is of a Puritanical bent; her father was vicar at Meopham. And you know J shares your convictions.”

“But you do not?”

“I worship on Sundays in the Church of England,” John said. “Where the king himself prays. If it is good enough for the king it is good enough for me.”

There was a discreet pause. “I think we might differ as to the king’s judgment,” Mr. Hurte volunteered. His wife, sitting lace-making at the fireside, gave him a sharp look and clattered the bobbins together on the pillow.

“But enough of that,” he said swiftly. “You’re the duke’s man and I’ve nothing to say against that. It is my daughter’s happiness we must consider. Does J earn enough to keep a wife?”

“He draws a full wage,” John said. “And they would live with us. I will see that she does not want for anything. Will she bring a dowry?”

“Fifty pounds now, and a third share of my shop at my death,” Josiah answered. “They can have the wedding here and I will treat them.”

“Shall I tell J he can propose, then?” John asked.

Josiah smiled. “If I know my daughter, he has already done so,” he said as they shook hands.

Spring 1628

Jane Hurte and young John Tradescant were married in the city church of St. Gregory by St. Paul. The officiating priest neither wore a surplice nor did he turn his back on the congregation to prepare communion as Archbishop Laud had ordered. The communion table was placed where tradition said it should be: at the head of the aisle, close to the communicants. And the vicar stood behind it, facing them like a yeoman of the ewry laying the lord’s table, doing his work in full sight of the congregation, and not like some secret papist priest hidden behind a screen, muttering over bread and wine and incense and water, with his back turned to the people he should be serving and his hands busy doing nobody knew what.

It was a good Baptist wedding and John, watching the priest about his business, serving his God and his congregation in the sight of them both, remembered the church at Meopham and his own wedding, which had been conducted the same way, and wished that Archbishop Laud had left things as they were, and not put honest men like him and Josiah Hurte on either side of a new divide.

Josiah Hurte gave them a good wedding dinner as he had promised and both sets of parents, the apprentice boys and half a dozen friends saw the young couple into their wedding chamber and put them to bed.

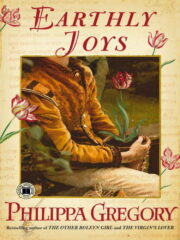

"Earthly Joys" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Earthly Joys". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Earthly Joys" друзьям в соцсетях.