Amanda Grange

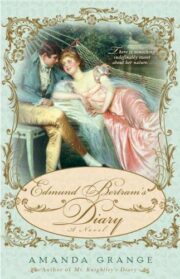

Edmund Bertram's Diary

1800 JULY

Tuesday 8 July

Tom was eager to try out his new horse’s paces and so we rode out together this morning, jumping walls and hedges, until he was satisfied he had made a good bargain.

‘Did you ever see such an animal?’ he asked me, as he reined in his horse. ‘I would never have been able to get him so cheap if Travis had not lost so heavily at cards. But Travis never learns. A man with such infernal luck should stick to spil ikins.’ He looked around him, letting his eyes wander over our father’s fields, down to the river at the bottom of the hill, and across the water to the woods beyond, but he did not see them as I did, as something to which he belonged. ‘I tell you, Edmund, I am longing to be free,’ he said. ‘I am tired of the country.’

‘We will soon be back at Eton.’

‘I am tired of Eton, too.’

‘It is not long now before we go to Oxford.’

‘Ay. Only one year more, and then I will be out in the world, instead of rotting away at school. I mean to have a fine time of it, I can tell you.’

‘What do you intend to study?’ I asked him, for it was a problem that vexed me, and I wondered if he had found the answer to it.

‘Women!’ he said, with a laugh. He turned to me. ‘But never fear, little brother, I will not seduce them all, I will leave one or two for you.’

And so saying, he wheeled his horse and raced for home.

I found myself thinking about Oxford as I raced after him. It is only two more years until I, too, will leave Eton and go up to university. I have still not thought how to answer Father’s question as to what I intend to do with the future. I have no taste for the Army or the Navy, but I must have something to do with my time, I suppose, and I hope the next few years will make my feelings clearer.

Friday 11 July

Aunt Norris was talking about little Fanny Price again this afternoon. Tom stood up as soon as she opened her mouth, for he is sick of hearing about it.

‘Let them do good if they must, but let them stop prattling about it beforehand!’ he muttered to me as he passed.

As I followed him, I heard Aunt Norris saying, ‘We must offer the child a home, for my poor sister has such a large family she cannot afford to look after them all...’

And my father saying, ‘It is a serious charge, for if we decide to take her in, we must adequately provide for her hereafter, or there will be cruelty instead of kindness in taking her from her family in Portsmouth.’

And Mama saying it was a great shame Mrs. Price had married to disoblige her family, settling on an idle fellow who was a lieutenant of marines, instead of looking higher and marrying a man of property. ‘For I am sure she was pretty enough to do so.’

I followed Tom as he headed for the stables.

‘What a fuss about a ten-year-old brat!’ he said. ‘Though I wonder my father is deceived by Aunt Norris’s profession of a desire to be useful. She will find an excuse not to take the brat when the time comes, you will see, and Mama and Papa will have to do it all.’ He looked up at the sky, where black clouds had started to gather. ‘It looks like rain. What say you we go into the barn and practice our archery?’

We did as he suggested, and I took pleasure in beating him soundly. He was put out, and blustered that he had not been paying attention.

We emerged from the barn an hour later, better from our exercise, and returned to the house, where we learnt that Tom’s prediction had come true. Aunt Norris had said that Uncle Norris was too ill to have a child in the house, and it has been settled that Fanny will come to us.

Saturday 12 July

Maria and Julia did nothing but complain about Fanny’s advent this morning as the four of us went riding, until Tom had had enough.

‘Why must you be so tiresome?’ he asked. ‘Can you not talk about anything else? You have done nothing but groan about Fanny since we came out.’ And to me he said, ‘This is our reward for allowing two silly little girls to accompany us on our morning ride.’

‘Julia might be a little girl, but I am almost a woman!’ said Maria indignantly. ‘It will not be long before I put my hair up and put my skirts down.’

‘You are only a year older than me,’ retorted Julia.

‘But it is an important year. There is a great deal of difference between thirteen and twelve,’ said Maria loftily.

‘Not so very much, and besides, Mama says I always behave like a lady.’

‘She says you must always behave like a lady,’ returned Maria. ‘That is not the same thing at all.’

An argument was brewing, and Tom forestalled it by proposing a race to the old barn. Julia crowed when she beat Maria, and Tom rewarded her by saying that he would dance with her after dinner.

‘And you had better dance with Maria,’ he said to me. ‘If we do not teach our sisters how to go on, they might end up marrying wastrels, and then we shall have to offer them charity and raise their brats in our nurseries.’

Maria declared she would marry a baronet. Julia trumped her by saying she would marry two baronets, at which we all began to tease her, until Julia, determined not to admit her blunder, said she would only marry the second one when the first was dead.

Sunday 20 July

I wish Tom would learn to sit still in church. He was fidgeting again during prayers and I was sure Mr. Norris would notice. Mr. Norris said nothing, however, and although Aunt Norris saw what was happening, she said nothing, either, for Tom can do no wrong in her eyes. It is a good thing Papa did not see, or he would have taken Tom to task for not setting a better example to the tenants.

AUGUST

Monday 4 August

Nanny set out this morning to fetch Fanny Price. Maria and Julia spent the day wondering about her appearance and her clothes and about her ability to speak French. Tom teased them, saying they were afraid she might be prettier and cleverer than they were, and they could settle to nothing all afternoon, plaguing the life out of Pug, until Mama finally roused herself and sent them up to the nursery.

Tuesday 5 August

Papa spoke to Tom and me at some length this afternoon, telling us that we must make Fanny welcome, but that some distinction of rank must be preserved.

‘You will see little of her, being away at school, but I would have you treat her with kindness and respect when you are here. And yet it would be wrong of you, or indeed any of us, to lead her to suppose she will have the same kind of future as Maria and Julia, for they are a baronet’s daughters, and will have a handsome dowry when the time comes for them to marry. Encourage Fanny to be useful and respectful. Praise her for her modesty and virtue, and show her by your manner that anything else is unbecoming in a little girl.’

We gave him our word, and Tom began to run as soon as we were out of the study.

‘Lord, I thought he would never finish! If we are not quick, the sun will have gone in and we will not get our swim.’

We went into the woods and dived into the pool. The water was bracing and full of weed, but we swam for an hour, for all that.

‘When I am Sir Thomas I will have the pool cleaned,’ said Tom grandly. ‘I will rid it of all this weed so that we may swim without becoming entangled in it.’

‘That will not be for many years, God willing,’ I said, ‘for Papa will have to die before you can become Sir Thomas.’

He laughed at me.

‘You are a good fellow, Edmund, but you take the lightest words so seriously. If you want to know what to do with your time when you are a man, you should go into the church. It will suit your serious nature.’

‘I might at that.’

‘If you do, have pity on me, and keep the prayers short. My knees were aching last Sunday.’

The rain began to fall and we retreated inside. Washed and dressed, I went downstairs. Mama was on the sofa, playing with Pug. Aunt Norris was telling Maria that her new hairstyle was very becoming, and that she would have a string of suitors when she was older; Julia was asking if she would have a string of suitors, too; and Tom was lounging on the chaise-longue, laughing at them.

Wednesday 6 August

Our visitor has arrived, and a small, frightened thing she is. I can scarcely believe she is ten years old; she looks closer to seven. Her eyes are large and her face thin; in fact, she is thin altogether. Her mother says she is delicate, and Papa has told us to be gentle with her. I believe such a child would provoke gentleness in anyone. She quaked whenever she was spoken to, and looked as though she wished to be anywhere but in the drawing-room. Papa was very stately in his welcome to her, and I believe his manner frightened her, though his words were kind. Mama’s smiles seemed to reassure her, and Maria and Julia, awed into their best behavior by Papa, added their welcome.

‘She is a very lucky girl,’ said Aunt Norris. ‘What wonderful fortune she has had, to be noticed by her uncle, and brought to Mansfield Park. It is not every child who is so lucky. You will be a good girl, I am sure, Fanny, and will not make us regret the day we brought you here. You must be on your best behaviour, if you please.’

Mama invited her to sit on the sofa next to Pug, and Tom, in an effort to cheer her, goodnaturedly gave her a gooseberry tart. She thanked him timidly and tried to eat it through her sobs, until Nanny rescued her, saying she was tired from her long journey, and took her up to the nursery.

Thursday 7 August

Maria and Julia were given a holiday so that they could get to know Fanny better, but they soon tired of her, remarking disdainfully, ‘She has but two sashes, and she has never learnt French.’

I saw her standing in the middle of the hall this afternoon looking lost and I asked her what she was doing. She blushed and clasped her hands and said that Aunt Norris had sent her to fetch her shawl from the morning-room, but that she did not know where it was. I undertook to show her the way, and said kindly, ‘What a little thing you are,’ but this seemed to make her more anxious so I made no further comments on her size. Once she had found the shawl I watched her until she disappeared safely into the drawing-room.

‘She looks at me as though I am a monster,’ said Tom when I mentioned it to him later. ‘I found her in the drawing-room this morning and asked her how she did. She did not reply, so I told her not to be shy, and she blushed to the roots of her hair.’

He suggested we go fishing, and we took our rods down to the river, where we caught several fish which were served up at dinner with a butter sauce.

Friday 8 August

Aunt Norris is very pleased with her protégée and after dinner, when Fanny had left the drawing-room, Mama and Papa remarked that Fanny seemed a helpful child who was sensible of her good fortune. Maria and Julia pulled faces at each other at the mention of Fanny, but said nothing more than that she seemed very small and always had the sniffles. I could not blame them, for she does always seem to be ill, poor child.

Wednesday 13 August

Tom and I rode out early, basking in the warmth. The dew was on the grass and all nature seemed to be waiting expectantly for the day to begin. Tom laughed when I said as much, and said I should become a poet.

We made a hearty breakfast and then he rode into town whilst I returned to my room. As I did so, I heard a strange sound, and I realized that it was sobbing. I followed it, to find our little newcomer sitting crying on the attic stairs.

‘What can be the matter?’ I asked her, sitting down next to her and wondering how to comfort her, for she looked very woebegone.

She turned a fiery red at being found in such a condition, but I soothed her and begged her to tell me what was wrong.

‘Are you ill?’ I asked her, for to tell the truth, she did not look well. She shook her head.

‘Have you quarreled with Maria or Julia?’ I asked, wondering if they had upset her.

‘No, no not at all,’ she whispered.

‘Is there anything I can get you to comfort you?’

She shook her head again. I thought for a moment and then asked, ‘If you were crying at home, what would you do to make yourself feel better?’

At the mention of home, her tears broke out anew, and it was easy to see where her sorrow lay.

"Edmund Bertram’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.