As soon as my father and I returned to the drawing-room for tea, I sat down next to Fanny and took her hand.

‘Fanny, I have been hearing all about your proposal,’ I said warmly. ‘I am not surprised. You have powers of attaching a man that another woman would envy, through your goodness and your purity of spirit. Now I see why Crawford put himself out to help William. He was helping his future brother-in-law!’

‘But I have refused him,’ she said quietly.

‘Of course, for the moment. But when you come to know him better you will see that he is just the sort of man to make you happy.’

She said no more but, feeling sure that she would soon change her mind, I let the matter drop and turned the conversation instead to William.

‘William is coming to stay with us, I understand,’ I said.

She brightened.

‘Yes, he will be here before long. He wants to see us all and thank us for our help in his promotion.’

‘Though it was all Crawford’s doing,’ I put in.

‘He would like to show us his uniform, too, but he is not allowed to wear it except on duty.’

‘Never mind. He will just have to describe it to us and we will then be able to imagine him in all his splendor.’

She talked on happily, looking forward to the day when she will see him again.

Wednesday 11 January

I was so heartened by Mary’s reception of me that I went over to Thornton Lacey this morning to give instructions for the farmyard to be moved, for I wanted to make the place respectable before showing it to Mary.

‘It needs to be over there, behind the copse, out of sight and downwind of the house,’ I said to the men.

They began to work, and I thought how big an improvement it would make to the property. I went into the house and looked into every corner, seeing what needed doing. Over luncheon I asked my father if I could borrow some more men to help me, and he gave me leave to take anyone I wanted.

This afternoon I returned to Thornton Lacey with Christopher Jackson. He followed me in, pausing just inside the front door, then swinging it back and forth and listening to it squeak.

‘This needs attention,’ he said.

‘See to it for me, will you, Jackson?’

He nodded, and we went through to the drawing-room. ‘There are some loose floorboards over here by the window. ’

‘Shouldn’t take too long,’ he said.

As we were about to leave the room he looked at the fire-place.

‘I could make you something better than that, something worth looking at,’ he said. ‘What this room needs is a carved chimney piece.’

I saw at once what he meant. The grate was a good size, and it would repay framing. An ornate chimney piece would give the room an elegant feel, and I could picture Mary sitting in front of it, playing her harp.

‘A good idea. Give me something worth having.’

His eyes lingered on the chimney, and I could tell he already had some ideas in mind. Upstairs, there were some cupboards that needed shelves, and a window frame that needed replacing. When we had been all round the house, I asked him to start work tomorrow. I rode back to Mansfield Park and changed, just in time for dinner. When I went downstairs I discovered that Crawford had called, and my father had invited him to stay for dinner. I wished he had brought his sister with him, but thought that, after all, perhaps it was a good thing he had not, as it would give me an opportunity to see him and Fanny together; if Mary had been present, I would have had eyes only for her.

I was hoping to see some signs of affection for him in Fanny’s face and demeanor, for I was sure that liking for the brother of her friend, gratitude towards the friend of her brother, and sweet pleasure in the honorable attentions of such a man, would combine to spread a warm glow over her face. A blush, a smile, a look of consciousness — these were the things I was expecting, but I did not see any of them. I was surprised but Crawford did not seem disturbed, and he sat beside her with an ease and confidence that spoke of his expectation of being a welcome companion. As he took a seat beside her, I thought her reserve and her natural shyness must soon be worn away. But no such thing. I tried to explain it to myself as embarrassment, but I thought Crawford must be really in love to press his suit with so little encouragement.

After dinner, luckily for Crawford, things improved. When we returned to the drawing-room, Mama happened to mention that Fanny had been reading to her from Shakespeare. Crawford took up the book and asked to be allowed to finish the reading. He began, and read so well that Fanny listened with great pleasure, gradually letting her needlework fall into her lap. At last she turned her eyes on him and fixed them there until he turned towards her and closed the book, breaking the charm.

She picked up her needlework again with a blush, but I could not wonder at Crawford for thinking he had some hope. She had certainly been enraptured by him and I thought that if he could win half so much attention from her in ordinary life he would be a fortunate man. I admired him for persevering, for it showed that he knew Fanny’s value, and knew that she was worth any extra effort he might have to make to overcome her reserve. And I could understand why he would not give her up, for as her needle flashed through her work, her gentleness was matched by her prettiness.

‘That play must be a favorite with you,’ I said to Crawford. ‘You read as if you knew it well.’

‘It will be a favorite, I believe, from this hour,’ he replied. ‘But I do not think I have had a volume of Shakespeare in my hand before since I was fifteen. But Shakespeare one gets acquainted with without knowing how. It is a part of an Englishman’s constitution. His thoughts and beauties are so spread abroad that one touches them everywhere; one is intimate with him by instinct.’

‘To know him in bits and scraps is common enough; to know him pretty thoroughly is, perhaps, not uncommon; but to read him well aloud is no everyday talent.’

‘Sir, you do me honor,’ said Crawford, with a bow of mock gravity.

‘You have a great turn for acting, I am sure, Mr. Crawford,’ said Mama soon afterwards; ‘and I will tell you what, I think you will have a theatre, some time or other, at your house in Norfolk. I mean when you are settled there. I do indeed. I think you will fit up a theatre at your house in Norfolk.’

‘Do you, ma’am? No, no, that will never be,’ Crawford assured her. I was surprised, for if the plays were well chosen, there could be no objection to Crawford setting up a theatre. He had a good income and was entitled to do with it, and his own home, as he wished. It would certainly give him an outlet for his talents, which were of no common sort in that direction.

Fanny said nothing but I am sure she must have guessed that Crawford’s avowal never to have a theatre must be a compliment to her feelings. She had made them known at the time of our disastrous theatrical affair and I was pleased that Crawford was willing to make such a sacrifice. It boded well for Fanny’s future happiness that he put her own wishes above his own. I asked Crawford where he had learnt to read aloud so well and Fanny listened intently to our discussion. I mentioned that it was not taught as it should be, and Crawford agreed.

‘In my profession it is little studied,’ I said, ‘but a good sermon needs a good delivery and I am glad my father made me read aloud as a boy, so that I could develop a clear and varied speaking voice.’

Crawford asked me about the service I had already performed and Fanny listened avidly. I admired Crawford, for he had found the way to her heart. She was not to be won by gallantry and wit, but by sentiment and feeling, and seriousness on serious subjects; something of which he showed himself eminently capable.

I drew away after a time, giving the two of them some time alone. I took up a newspaper, hoping that Fanny would be persuaded to talk to her lover, and I gave them my own murmurs: ‘A most desirable Estate in South Wales’; ‘To Parents and Guardians’; and a ‘Capital season’d Hunter’ to cover their own.

It did not seem to go well, from what I heard, for Fanny seemed to be berating Crawford for inconstancy, and though I tried not to listen I could not help their words reaching me.

‘You think me unsteady: easily swayed by the whim of the moment, easily tempted, easily put aside,’ I heard Crawford say. ‘With such an opinion, no wonder that... But we shall see. It is not by protestations that I shall endeavor to convince you I am wronged; it is not by telling you that my affections are steady. My conduct shall speak for me; absence, distance, time shall speak for me. They shall prove that, as far as you can be deserved by anybody, I do deserve you. You are infinitely my superior in merit; all that I know. You have qualities which I had not before supposed to exist in such a degree in any human creature. You have some touches of the angel in you beyond what — not merely beyond what one sees, because one never sees anything like it — but beyond what one fancies might be. But still I am not frightened. It is not by equality of merit that you can be won. That is out of the question. It is he who sees and worships your merit the strongest, who loves you most devotedly, that has the best right to a return.’

I was surprised to hear such ardor, and was just beginning to be uncomfortable at overhearing it when Baddeley brought in the tea. Crawford was obliged to move and I returned to the group. Fanny said no more but I felt she could not have been unmoved by Crawford’s protestations. I was expecting her to speak to me when he left but she kept silent. I did not ask her about him, for I did not want to press her. But as I have always been her confidant, I hope she will turn to me when she feels she needs someone to talk to.

Thursday 12 January

As I dressed this morning, I found myself wondering what Mary thought of her brother’s feelings for Fanny. I knew she was fond of Fanny, but I also knew that she had a high regard for wealth and distinction, and I thought she might feel that Henry should unite himself to both. I rode over to Thornton Lacey and found that the work was going on apace. There was already a difference in the size of the farmyard and Jackson was at work on the door. The fine weather was helpful, and I went round to the stables to ascertain whether there would be room to keep my horses as well as a mount for Mary. There would, perhaps, be enough room but I felt it would be better to extend the stables, something which could be easily done, and I spoke to Jackson about it before leaving.

Returning to Mansfield Park, I found myself wondering again about Mary’s view on her brother’s choice of bride. We were dining at the Parsonage, and I resolved to broach the subject, but in the event there was no need, for she began to speak of it herself not five minutes after I had arrived.

‘Well, Mr. Bertram, and what do you think of my brother and Miss Price?’ she asked. Mrs. Grant laughed at her for her rapidity, saying, ‘Mary, give Mr. Bertram time to sit down, at least!’

‘But I want to know,’ she said.

‘I confess I was surprised,’ I returned.

‘Were you? I was not. I have been seeing his attachment for some time, and seeing it with pleasure. There is not a better girl in all the world than Fanny Price. Her gentleness and gratitude are of no common stamp, and I am glad that Henry has seen it. She has nothing of ambition in her, and she is the only woman I have ever met who would not be swayed by Henry’s fortune and his estate. Only love will do for Fanny Price.’

‘There you are right,’ I said.

‘Such a beautiful girl,’ said Mrs. Grant. ‘Henry has been full of her charms. Her face and figure, her graces of manner and goodness of heart are exhaustless themes with him. He talks of nothing else.’

‘Unless it be her temper, which he has good reason to depend on and praise. He has often seen it tried, for Mrs. Norris is unstinting in her criticisms, and yet Fanny never answers her sharply,’ said Mary.

‘No, indeed, I have never heard her speak a word of complaint, ’ said Mrs. Grant.

‘She is sometimes too forbearing, and needs a champion,’ I said.

‘Oh! Henry will champion her, should there ever be a need, but why will there be, when he takes her away to her own home? There will be no aunt there to criticize her, only a husband who loves her, and a staff whose business it will be to make sure she is comfortable in every way. There is only one fault I have to find in her, and that is that she has refused Henry. For that I am very angry with her!’

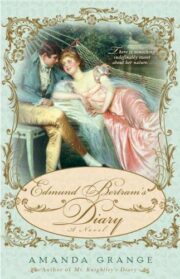

"Edmund Bertram’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.