Tom was morose when I mentioned that we would soon be back at school, but then he brightened.

‘Only one more year, Edmund,’ he said. ‘Only one more, and then I will be up at Oxford. And in two years we will be there together.’

1802 NOVEMBER

Tuesday 9 November

I wondered what Oxford would be like, and whether I would take to it, but now that I am here I find I am enjoying myself. Tom came to my rooms when I had scarcely arrived and told me he would take care of me. He hosted a dinner for me tonight and it was a convivial evening, though I was surprised to see how much he drank. At home, he takes wine in moderation, but tonight he seemed to know no limit. I held his hand back as he reached for his third bottle, asking him if he did not think he had had enough, and he laughed, and said that he would not listen to a sermon unless it was on a Sunday, and at this his friends laughed, too. I felt uncomfortable but I suppose I must grow used to some wildness now that I am no longer at school.

Wednesday 10 November

Whilst coming back from Owen’s rooms in the early hours of this morning I saw a fellow lying across the pavement. I was afraid he was ill, for I saw that he had been sick but, on approaching him, I smelt spirits and realized he was only drunk. I was about to step over him in disgust when I saw that it was Tom. His mouth was slack and his skin was pasty. His clothes were soiled, which distressed me greatly, for he has always been very particular about his dress. Many a time have I seen him berate his valet for leaving a fleck of dust on his coat or a bit of dirt on his boot, and to see him in such a state...

I tried to rouse him but it was no good, and so in the end I picked him up: no easy feat, for he is a good deal heavier than he used to be, and carried him back to his rooms.

Thursday 11 November

I called on Tom this afternoon and found him sitting on his bed with the curtains drawn, nursing his head. He said he had had a night of it, and that he could not remember how he got back to his rooms. I told him I had carried him.

‘What, so now you are a porter, little brother?’ he said, and laughed, but the laugh made his head ache and he clutched it again.

‘You should not get in such a state, Tom. What would Mama say?’ I asked, hoping that thinking of her would bring him back to his senses.

‘She would say, “Tell Sir Thomas. Sir Thomas will know what to do,” ’ he said, mimicking her. I did not like to hear him making fun of her, but I knew it would do no good to remonstrate with him. It would only make him laugh at me or, if he was in a bad mood, grow impatient.

‘Just try not to drink so much tonight,’ I said.

‘Always my conscience, eh, Edmund?’

‘You need one,’ I told him. ‘As long as you are all right, I will go. I have some work to do before dinner.’

‘You work too hard.’

‘And you do not work at all.’

‘You sound like Papa,’ he said testily.

‘You make me feel like him,’ I returned, and then I felt dissatisfied, for Tom and I have always been friends.

I tried to say something softer but he only cursed me. I saw that there was no talking to him whilst his head was so sore, and so I left him to himself and sought out Laycock instead.

Monday 15 November

Tom called on me this afternoon and my spirits sank, for he only ever comes to my room now to ask for money. He told me that he had lost heavily at cards last night and had exhausted his allowance.

‘It is a debt of honor and I must pay it,’ he said. ‘I need twenty pounds.’

I gave it to him, but I told him that it was the last time I would help him.

‘You might have money to lose, but I do not,’ I said.

‘Why worry? You are already provided for. You will have the Mansfield living when you take orders, and the living of Thornton Lacey as well. You will not be poor.’

‘If I go into the church. I might not.’

‘Oh, what else are you thinking of doing?’ he asked curiously, as he sat down on the sofa and crossed one leg over his knee.

‘That is the problem, I do not know,’ I said with a sigh as I sat down next to him.

‘You take everything too seriously, Edmund.’

‘And you do not take things seriously enough.’

‘Then we make a good pair, for we balance each other’s faults. But do not go into the church if you do not like the idea.’

‘I have not said that I will not, only that I am not sure. There is a lot of good I could do—’

‘You sound like Aunt Norris!’

I shuddered at the notion, and said quickly, ‘Perhaps I may go into the law instead.’

‘A good alternative, for there is decidedly no chance of you doing good there. Papa would find it harder to help you, though,’ he said more seriously.

‘Then I will have to do what everyone else does, and manage on my own.’

‘In that case, you must have your fun now,’ he said, standing up. ‘Come, I insist. Kreegs is having a party at his rooms this afternoon — a sedate party,’ he said, seeing my look. ‘No drinking, no gambling, no women — unless you count his mother and sister. He is entertaining them to tea.’

‘Well...’

‘Miss Kreegs is very pretty,’ he said temptingly. ‘You should marry, Edmund, you are the type. Marry someone as sensible as yourself, then you and your wife can sit at home in the evenings in your slippers, with your noses in a couple of books!’

I punched him playfully and he responded in kind, and before long we were wrestling as we used to when we were at school.

‘Do you ever wish we were boys again?’ he asked.

‘Never,’ I said.

But it was not quite true. Sometimes I wish that life could be as simple as it was when I was at school, when I did not have to decide on anything more important than whether to have an extra slice of pie for dinner, and my problems were no deeper than the difficulties of learning Latin verbs.

‘No!’ he said, but he did not sound convinced. ‘Neither do I.’

Wednesday 17 November

I wrote to Mama and told her how I was going on, adding my love for my sisters and for Fanny. I wrote separately to my father and gave him news of my studies, whilst thanking him for my allowance. I wondered whether to say something about Tom, for he was drunk all day yesterday and could not crawl out of bed, but I decided that loyalty outweighed every other feeling. I often wonder, if Tom had been the younger and I the elder, would I have been more highspirited and would he have been more studious? Or is the difference between us in our characters, and would he have been wild and I serious whatever the case?

Friday 19 November

Owen has invited me to spend some time with his family near Peterborough when we break up for the Christmas holidays, and I have accepted.

DECEMBER

Monday 20 December

It is good to be home. I was met by kindness from Mama, enquiries about my health from Mrs. Norris, judicious interest from Papa, squeals from Maria and Julia, a shamefaced anxiety from Tom — which, however, evaporated when it became clear that I did not mean to mention any of his university exploits — and unabashed happiness from Fanny. The way her face lit up when she saw me lifted my spirits, and it was not long before we were outside.

‘Are you sure you are warm enough?’ I asked her, for the air was cold even though the sun was shining.

‘Yes,’ she said.

‘Let me look at you to be sure.’

I cast my eyes over her cloak, which she wore over her pelisse, and saw that her bonnet was pulled down over her ears, and that her hands were gloved as well as being hidden in her muff.

‘Yes, I think you are.’

As we began our walk I asked her what she had been reading. She had read the Goldsmith I recommended, and we were soon so engrossed in the conversation that we lost track of the time, being taken by surprise when we discovered that dusk was falling. We returned to the house. Just before we went in I took the opportunity of quizzing her on the constellations, which were beginning to appear in the sky, and I found she had memorized all that we could see.

We went inside and I returned to my room to find Tom lolling there, bored. He sat and talked whilst I dressed for dinner and then we went downstairs. After dinner I called Fanny to me, for I saw my aunt’s eyes on her and suspected Fanny would soon be sent on an errand through the cold corridors if I did not keep her by my side. She repaid me by telling me all about the letter she had had from her family, and regaling me with stories about Susan and William.

Tuesday 21 December

Tom thanked me for not mentioning his conduct to Papa. I told him I would never betray him, and said how glad I was to see him looking better for being at home. He told me it was just high spirits that made him wild at Oxford, and I should join him in his pleasures.

‘There will be time enough to be sober when you are older,’ he told me.

‘After seeing you lying face down in the quad, I would rather be sober now,’ I said. I think that is why I have never succumbed to the worst temptations university life has to offer. Tom has always been there before me, and shown me the evil of excess by his example. If he could only see himself when he is drunk I am sure he would be as disgusted with it as I am. He looked annoyed, but his face soon cleared and he challenged me to a race over to Hampton’s Cross. I accepted the challenge, and I would have beaten him if my horse had not thrown a shoe. He laughed at me when I said as much, saying he had been letting me edge into the lead to humour me, and that he would have overtaken me before we reached the cross. We were still arguing the point when we returned to the house. We had hearty appetites and begged some food from Mrs. Hannah in the kitchen, knowing it was still some hours until dinner. She gave us a hunk of roast beef and a loaf to share between us, and we ate it hungrily before returning to our rooms.

After dinner we had an impromptu ball and Tom taught us all a new dance. He could not remember half the steps, but the girls enjoyed it. Aunt Norris said she had never seen finer dancing, remarking that Maria would have many admirers when she came out. Julia went into a pet, and Tom teased her out of it, saying she would no doubt marry a prince, and we ended the evening very merrily.

1803 APRIL

Thursday 7 April

The weather is remarkably fine and I am enjoying my holiday. I decided to ask Fanny if she would like to go for a ride with me this morning, but when I went into the drawing-room I found her opening a letter from Portsmouth. I did not like to disturb her so I sat down for a few minutes and let her read in comfort, whilst Aunt Norris busied herself about her sewing and Mama played with Pug.

I was surprised to hear a choked sob from Fanny and, looking up, I saw that she was crying. I went over to her at once.

‘Fanny, my dear, whatever is wrong?’

I took the letter from her hand, as she could not speak, and read the sad news, that her sister Mary had died.

‘What is it? What is wrong?’ asked Aunt Norris.

‘Fanny’s sister has died,’ I told her.

Mama murmured kind words of sympathy, and offered Fanny Pug to play with. It was a kind offer, but Fanny declined it, being too distressed for Pug to cheer, whilst Aunt Norris said only,

‘A blessing for my sister, for she has so many children, she will not miss one.’

I gave her an angry look and took Fanny into the library, where I took her head on my shoulder and let her cry.

‘She was such a pretty little thing,’ said Fanny, clutching her handkerchief. ‘I believe I loved her even more than I loved Susan. She was only five years old. If only I had known! I should have been with her. I could have nursed her. I could have helped Mama to take care of her.’

‘Your mother and Susan looked after her,’ I soothed her. ‘They did all they could. No one could have done more, not even you, my dear. Now dry your eyes, Fanny, do, for I cannot bear to see you so distressed. Your sister is with God now.’

She took comfort from this and her tears changed to healthy tears. I comforted her until her sobbing ceased.

I took pains to cheer her this evening, and, having told Maria and Julia what had happened, and begged their kindness for her, I found them very affectionate. Maria asked Fanny if she would like to help her trim a bonnet and Julia gave her a silver thimble. As I watched them I thought again about making the church my career. I know Papa would like it, for he could give me the family livings, but it is not something I could do without a vocation. And yet I am beginning to think I have one. I found it natural to help Fanny in her time of grief, and though I have a great affection for her that I do not have for other people, I think I could help them, too.

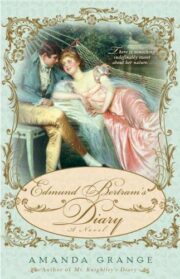

"Edmund Bertram’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.