“And here you work so hard to create the impression you have no loyalty, save to coin of the realm.”

Benjamin sipped his drink placidly. “Don’t be tiresome, your lordship.”

“My intentions are not contrary to Mr. Grey’s interests, but this moving on with his life you refer to does not comport with either his brother’s or my impression of the man. He does not socialize, he does not belong to a club, he does not ride to hounds with the locals except for the informal meets, and he does not attend services. Until recently, I’m not sure he knew which son was which. He sits, like a spider, in the middle of a financial web and spins money at a rate that impresses the Regent.”

“And this is a crime, to do what one does well?”

“To let life go by in every sphere save one is a tragedy. My marchioness says we have neglected our neighbor, and my conscience has agreed with her, as it is wont to do. He has not moved on with his life, Benjamin. I know when somebody is mired in their past, because I’ve been in the same slippery ditch myself.”

“It still isn’t like you to interfere, conscience or not.” Personal disclosures were not like Heathgate either, much less unflattering personal disclosures.

“I won’t interfere. I will simply ensure Mr. Grey has the information necessary to make prudent decisions in a timely manner. He does that well in the commercial realm, and if your sister’s affections are returned, he should be motivated now to do so regarding personal matters as well.”

“I would not want you for an enemy, Heathgate.” Benjamin rose and set his empty glass aside.

“My sentiments as well.” Heathgate set his glass aside too, his face creasing into a startlingly charming smile. “Now that we’ve covered my neighbor’s situation, come to the nursery with me. James, Will, and Pen will want to see you, and Joyce will want to see me.”

“Your marchioness will want to see you.” And to his credit, Benjamin managed to sound not the least envious as he made that observation.

The anniversary of Barbara’s death came and went, and when Ethan realized he noticed the significance of the date only in hindsight, he had to consider he was putting Barbara’s death behind him. For the previous two years, his mourning period completed, he’d gone off to hunt grouse in Scotland or Cumbria—or to pretend he was hunting grouse.

He’d consider it sport when the birds were given guns to defend themselves, though he’d never dare express such an opinion to another.

He continued to meet up occasionally with Heathgate on the bridle paths, and sometimes with Lords Greymoor and Amery as well, all of whom were fascinated with their offspring’s every peccadillo and sniffle.

This would have been a trial, except Ethan was fascinated himself. His children entranced him, with their funny little opinions, their odd fears, and their willingness to be silly over nothing. He liked the way they’d argue fiercely with each other one minute, and then be off to whisper in the corner the next. He liked the way each boy understood the other, and even in the midst of pitched battle, would tread lightly in certain areas.

He liked that they were affectionate, particularly since Uncle Nick’s parting admonition to Jeremiah had been a whispered order to tickle Ethan at least every other day. That wouldn’t last—boys grew up and acquired dignity—but it had given Ethan a pretext for hugging his children and wrestling with them in the grass from time to time.

And if the children weren’t thawing years of reserve, Alice certainly was. She was shy of her own body, but eager regarding Ethan’s. She’d touch him in little ways throughout the day if they were alone—smooth his cravat, take off his spectacles, squeeze his hand—and she was something else entirely at night.

Scholars were a curious lot, and Alice was inherently a scholar. She took off his clothes and studied him. She touched and tasted and even listened to his body, pressing her ear over his heart or lungs and then, satisfied he was quite alive, over his belly.

“It’s how you diagnose a colicky horse,” she’d said, frowning up at him.

And then she’d listened to him laugh.

They hadn’t made love—yet. Not in the traditional sense of the phrase, anyway. Ethan told himself he was giving her time to change her mind, but in truth, he wasn’t ready. He blamed his unreadiness on Gareth Alexander, Marquis of Heathgate, neighbor and Inconvenience at Large.

Since Nick’s visit, Ethan had felt the presence of neighbors in his life, and not just on his bridle paths. Twice, the boys had been invited to Willowdale to play with Heathgate’s children. Twice, Ethan had been to dinner, once at Heathgate’s, once at Greymoor’s. They were an informal, affectionate lot, even when the children were not in evidence. The only one of the group with whom Ethan felt truly comfortable was Amery, the quietest one of the bunch.

The hardest shock to bear was that these people touched him, physically. The ladies kissed his cheek and took his arm as if he were a long-lost cousin. The men were forever cramming themselves together on sofas and settles, sipping their drinks at the end of the day. They teased and fell silent, alluded to the occasional problem, and laughed gently at one another. It puzzled Ethan to be included in such goings-on, and he was growing to tolerate it better than he would have predicted.

Growing almost comfortable with it, except every time he began to lose track of his separateness, he’d look up to find Heathgate watching him. The marquis’s eyes held the same questions he’d battered Ethan with the day Nick left: Why don’t you feel compassion for the boy you were? Why do you feel ashamed of him?

And Ethan wished, as the air began to take on a hint of autumn, he could talk to Nick. Now, when Nick was busy with his earldom and his new wife and six other siblings, Ethan let himself miss his brother. He didn’t want to burden Nick with superfluous confidences, but he missed his brother.

He just… missed him.

“Miss Alice?” Joshua was preparing for a midafternoon nap, which was unusual. That he was accepting the need without protest was more unusual still.

“Joshua?” Alice sat on his bed. He looked a little pale, but then, he was an Englishman’s son, and Alice had never seen his color high.

“If you said you wouldn’t tell a secret,” Joshua began, “but then something else happened, so you had not just one secret, but two, does the first promise not to tell mean you can’t tell the second time either?” Alice frowned and tried to puzzle through the riddle that was part logic and part little-boy inquiry into the heady topic of manly honor.

“Give me an example.”

Joshua’s brow puckered in thought. “If I saw Papa up reading past his bedtime, but I promised not to tell, then I saw him doing it again, should I tell?”

“Before you tell, you should confront him directly and give your papa a chance to explain, unless you think it isn’t safe to do so.”

Joshua fingered the hem of his coverlet. “Papa doesn’t hit. Why wouldn’t it be safe?”

“I don’t know. I once didn’t tell my brothers something, because I was afraid they’d go try to beat up someone for me, and I didn’t want them taking that risk.”

“Are your brothers as big as Papa?”

“Not quite, and they were quite a bit younger at the time. Now close your eyes. Do you want me to read to you?”

“Yes, Miss Alice.” His yawn was genuine, and before Alice could select a soothingly familiar story, he was asleep.

“Is he all right?” Jeremiah’s voice was laced with anxiety.

Alice smiled at the boy hovering in the doorway. “I think he’s just worn out from trying to keep up with his brilliant older brother. He’ll be fine.”

Jeremiah came to stand beside her, looking down at his younger brother. “I heard him ask about secrets.”

“It was a good question.”

“Did you ever tell your brothers?” Jeremiah asked, still frowning at Joshua’s sleeping form.

“I did not,” Alice said, wondering what mysteries were churning in Jeremiah’s too-busy little brain.

“Maybe you should. I think I’ll take a nap too.”

“You don’t have to,” Alice said. “If you’re not tired, it can just make it harder to sleep at night.” And God knew, the last thing she wanted was for the little boys to be up wandering around when she was misbehaving with their father at night.

Ethan slipped behind Alice in the library and wrapped his arms around her waist, feeling her curl back against him on a sigh. “Can I ask you something?”

Lemon verbena had become his favorite scent. It brought to mind not just Alice, but the sheets on her bed, where Ethan had spent many pleasant hours.

“You’ve asked me a great deal lately, Ethan Grey: my favorite flower, my favorite author, my political opinions, my name day, and my birthday.”

He hadn’t asked her to make love with him, and they both knew it. She wrapped her hands over his at her midriff. “Ask me, Ethan.”

“We have on occasion mentioned the scandal in your past,” Ethan said. “If there were scandal in my past, personal in nature, would you want to know?” The answer to this question mattered, and had something to do with Ethan’s reluctance to consummate their dealings, much as he wished that were not so.

Also with his inability to go for long without touching her.

“I know about your wife.” Alice slipped from his hold and turned to face him, defeating his hug-her-from-behind-so-she-won’t-see-your-face strategy. “And you’ve told me Joshua may not be your son. What could be more personal than that?”

“Joshua is every bit my son. But about the scandal, you’d want to know?”

“If you wanted to tell me, I’d be happy to listen, but what befell you in the past matters a great deal less than who you are now, at least to me.”

Bless this woman. “Even if it’s a very bad business, Alice?” Ethan looked past her, out across the back gardens in the direction of the Marquis of Heathgate’s holdings. Part of him wanted to tell her, not to weather her reaction, but to repose his whole self, past, present, and future, in her keeping. “Even if it’s something that might make you ashamed to consort with me?”

“I could never be ashamed of you, and as to that, we don’t quite consort, Ethan. This is beginning to puzzle me, because I am willing, and you seem interested, and yet we don’t… Have you lost interest?”

She sounded bewildered and a trifle hurt. He could not abide either.

“No, never.” Ethan jammed his hands into his pockets to keep from reaching for her. “But conception is an issue, and the timing hasn’t been right.” That was true, as far as it went.

“I don’t understand.”

“Your courses came just after…” Ethan paused, searching for delicacy. “After the picnic at Heathgate’s.”

“And?”

“And I would not importune you at such a time.” Ethan felt color rising across his cheeks. He took her by the wrist and pulled her to a printed calendar hanging behind his desk. There were marks on it in pencil—ships arriving, contracts due, payments to be made—but he tapped his finger on the date of the picnic.

“I think you started your courses here.” He shifted his finger two days. “Am I right?”

“You are.” And it was Alice’s turn to blush. “How did you know?”

“Your breasts were more sensitive then.” Ethan kept his gaze on the calendar. “And you were… affectionate and quiet, but would not encourage certain types of advances, and then you asked me to let you catch up on your sleep for a few nights.”

“And you took that to mean I was indisposed?”

“I hoped it meant that.” Ethan glanced at her fleetingly, not sure whose modesty he was sparing. “Not that you were having second thoughts.”

“Why would you think that?”

Ethan’s gaze went back to the calendar. “Perhaps we might finish with our earlier topic?” He was dodging. He knew it, and she knew it, but they tacitly agreed not to confront the knowledge—yet.

“Please. I can’t help but feel embarrassed you should know of these things and I would not.”

“I kept a mistress,” Ethan reminded her, “a woman with whom procreation was my last intention. The knowledge became relevant too late to do me any good.”

“This is very… intimate.”

There, on that date a few days after the picnic, Ethan had made one small mark—a little cross, and the significance of it was known only to him and her. He liked that; she was probably mortified by it.

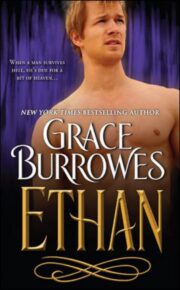

"Ethan: Lord of Scandals" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ethan: Lord of Scandals". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ethan: Lord of Scandals" друзьям в соцсетях.