He nodded and ran his eyes over her, obviously liking what he saw. "You need a lift into town?"

She stood and wiped her hair out of her eyes with her forearm, trying to seem casual. "No. Somebody's picking me up." She inclined her head toward the mess, her resolution not to begin her new life with lies already abandoned. "Miss Padgett told me I had to finish this tonight before I left. She said I could lock up." Did she sound too offhand? Not offhand enough? What would she do if he refused?

"Suit yourself." He gave her an appreciative smile. A few minutes later she let out a slow, relieved breath as she heard the front door close.

Francesca spent the night on the black and gold office sofa with Beast curled against her stomach, both of them poorly fed on sandwiches she had made from stale bread and a jar of peanut butter she found in the kitchenette. Exhaustion had seeped into the very marrow of her bones, but still she couldn't fail asleep. Instead, she lay with her eyes open, Beast's fur pushed into the V's between her fingers, thinking about how many more obstacles lay in her way.

The next morning she awakened before five and promptly threw up into the toilet she had so painstakingly cleaned the night before. For the rest of the day, she tried to tell herself it was only a reaction to the peanut butter.

"Francesca! Dammit, where is she?" Clare stormed from her office as Francesca flew out of the newsroom where she'd just finished delivering a batch of afternoon papers to the news director.

"I'm here, Clare," she said wearily. "What's the problem?"

It had been six weeks since she'd started work at KDSC, and her relationship with the station manager hadn't improved. According to the gossip she'd picked up from members of the small KDSC staff,

Clare's radio career had been launched at a time when few women could get jobs in broadcasting. Station managers hired her because she was intelligent and aggressive, and then fired her for the same reason. She finally made it to television, where she fought bitter battles for the right to report hard news instead

of the softer stories considered appropriate for women reporters.

Ironically, she was defeated by Equal Opportunity. In the early seventies when employers were forced

to hire women, they bypassed battle-scarred veterans like Clare, with their sharp tongues and cynical outlooks, for newer, fresher faces straight off college campuses-pretty, malleable sorority girls with degrees in communication arts. Women like Clare had to take what was left-jobs for which they were overqualified, like running backwater radio stations. As a result, they smoked too much, grew increasingly bitter, and made life miserable for any females they suspected of trying to get by on nothing more than a pretty face.

"I just got a call from that fool at the Sulphur City bank," Clare snapped at Francesca. "He wants the Christmas promotions today instead of tomorrow." She pointed toward a box of bell-shaped tree ornaments printed with the name of the radio station on one side and the name of the bank on the other. "Get over there right away with them, and don't take all day like you did last time."

Francesca refrained from pointing out that she wouldn't have taken so long last time if four staff members hadn't dumped additional errands on her-everything from delivering overdue bills for air time to having a new water pump put in the station's battered Dodge Dart. She pulled on the red and black plaid car coat she'd bought at a Goodwill store for five dollars and then grabbed the key to the Dart from a cup hook next to the studio window. Inside, Tony March, the afternoon deejay, was cuing up a record. Although he hadn't been with KDSC very long, everyone knew he would be quitting soon. He had a good voice and a distinct personality. For announcers like Tony, KDSC, with its unimpressive 500-watt signal, was merely a stepping stone to better things. Francesca had already discovered that the only people who stayed at KDSC for very long were people like her who didn't have any other choice.

The car started after only three attempts, which was nearly a record. She backed around and headed out of the parking lot. A glance at the rearview mirror showed pale skin, dull hair snared at the back of her neck with a rubber band, and a red-rimmed nose from the latest in a series of head colds. Her car coat was too big for her, and she had neither the money nor the energy to improve her appearance. At least she didn't have to fend off many advances from the male staff members.

There had been few successes for her these past six weeks, but many disasters. One of the worst had occurred the day before Thanksgiving when Clare had discovered she was sleeping on the station couch and screamed at her in front of everyone until Francesca's cheeks burned with humiliation. Now she and Beast lived in a bedroom-kitchen combination over a garage in Sulphur City. It was drafty and badly furnished with discarded furniture and a lumpy twin bed, but the rent was cheap and she could pay it by the week, so she tried to feel grateful for every ugly inch of it. She had also gained the use of the station's Dodge Dart, although Clare made her pay for gas even when someone else took the car. It was an exhausting, hand-to-mouth existence, with no room for financial emergencies, no room for personal

emergencies, and no-absolutely no-room for an unwanted pregnancy.

Her fists tightened on the steering wheel. By doing without almost everything, she had managed to save the one hundred and fifty dollars the San Antonio abortion clinic would charge her to get rid of Dallie Beaudine's baby. She refused to let herself think of the ramifications of her decision; she was simply too poor and too desperate to consider the morality of the act. After her appointment on Saturday, she would have averted one more disaster. That was all the introspection she allowed herself.

She finished running her errands in little more than an hour and returned to the station, only to have

Clare yell at her for having gone off without washing her office windows first.

The following Saturday she got up at dawn and made the two-hour drive to San Antonio. The waiting room of the abortion clinic was sparsely furnished but clean. She sat down on a molded plastic chair, her hands clutching her black canvas shoulder bag, her legs pressed tightly together as if they were unconsciously trying to protect the small piece of protoplasm that would soon be taken from her body. The room held three other women. Two were Mexican and one was a worn-out blonde with an acned face and hopeless eyes. All of them were poor.

A middle-aged, Spanish-looking woman in a neat white blouse and dark skirt appeared at the door and called her name. "Francesca, I'm Mrs. Garcia," she said in lightly accented English. "Would you come with me, please?"

Francesca numbly followed her into a small office paneled in fake mahogany. Mrs. Garcia took a seat behind her desk and invited Francesca to sit in another molded plastic chair, differing only in color from the one in the waiting room.

The woman was friendly and efficient as she went over the forms for Francesca to sign. Then she explained the procedure that would take place in one of the surgical rooms down the hall. Francesca bit down on the inside of her lip and tried not to listen too closely. Mrs. Garcia spoke slowly and calmly, always using the word "tissue," never "fetus." Francesca felt a detached sense of gratitude. Ever since

she had realized she was pregnant, she had refused to personify the unwelcome visitor lodged in her womb. She refused to connect it in her mind to that night in a Louisiana swamp. Her life had been pared down to the bone-to the marrow -and there was no room for sentiment, no room to build falsely romantic pictures of chubby pink cheeks and soft curly hair, no need ever to use the word "baby," not even in her thoughts. Mrs. Garcia began to speak of "vacuum aspiration," and Francesca thought of the old Hoover she pushed around the radio station carpet every evening.

"Do you have any questions?"

She shook her head. The faces of the three sad women in the waiting room seemed implanted in her mind-women with no future, no hope. Mrs. Garcia slid a booklet across the metal desktop. "This pamphlet contains information on birth control that you should read before you have intercourse again."

Again? The memory of Dallie's deep, hot kisses rushed back to her, but the intimate caresses that had once set her senses aflame now seemed to have happened to someone else. She couldn't imagine ever feeling that good again.

"I can't have this-this tissue," Francesca said abruptly, interrupting the woman in midsentence as she showed her a diagram of the female reproductive organs.

Mrs. Garcia stopped what she was saying and inclined her head to listen, obviously accustomed to hearing the most private revelations pass across her desk.

Francesca knew she had no need to justify her actions, but she couldn't seem to stop the flow of words. "Don't you see that it's impossible?" Her fists clenched into knots in her lap. "I'm not a horrible person. I'm not unfeeling. But I can barely take care of myself and a walleyed cat."

The woman gazed at her sympathetically. "Of course you're not unfeeling, Francesca. It's your body,

and only you can decide what's best."

"I've made up my mind," she replied, her tone as angry as if the woman had argued with her. "I don't have a husband or money. I'm barely hanging on to a job working for a boss who hates me. I don't even have any way to pay my medical bills."

"I understand. It's difficult-"

"You don't understand!" Francesca leaned forward, her eyes dry and furious, each word coming out like

a hard, crisp pellet. "All my life I've lived off other people, but I'm not going to do that anymore. I'm going to make something of myself!"

"I think your ambition is admirable. You're obviously a competent young-"

Again Francesca pushed aside her sympathy, trying to explain to Mrs. Garcia-trying to explain to herself-what had brought her to this red brick abortion clinic in the poorest part of San Antonio. The room was warm, but she hugged herself as if she felt a chill. "Have you ever seen those pictures people put together on black velvet with little nails and different colored strings-pictures of bridges and butterflies, things like that?" Mrs. Garcia nodded. Francesca gazed at the fake mahogany paneling without seeing it. "I have one of those awful pictures fastened to the wall, right above my bed, this terrible pink and orange string picture of a guitar."

"I don't quite see-"

"How can someone bring a baby into the world when she lives in a place with a string picture of a guitar on the wall? What kind of mother would deliberately expose a helpless little baby to something so ugly?" Baby. She'd said the word. Twice she'd said it. A painful press of tears pricked at the backs of her eyelids but she refused to shed them. In the past year, she'd cried enough spoiled, self-indulgent tears to last a lifetime, and she wasn't going to cry any more.

"You know, Francesca, an abortion doesn't have to be the end of the world. In the future, the circumstances may be different for you… the time more convenient."

Her final word seemed to hang in the air. Francesca slumped back in the chair, all the anger drained out

of her. Was that what a human life came down to, she wondered, a matter of convenience? It was inconvenient for her to have a baby right now, so she would simply do away with it? She looked up at Mrs. Garcia. "My friends in London used to schedule their abortions so they wouldn't miss any balls or parties."

For the first time Mrs. Garcia visibly bristled. "The women who come here aren't worried about missing

a party, Francesca. They're fifteen-year-olds with their whole lives in front of them, or married women who already have too many children and absent husbands. They're women without jobs and without any hope of getting work."

But she wasn't like them, Francesca told herself. She wasn't helpless and broken anymore. These past few months she had proven that. She'd scrubbed toilets, endured abuse, fed and sheltered herself on next to nothing. Most people would have crumbled, but she hadn't. She had survived.

It was a new, tantalizing view of herself. She sat straighter in the chair, her fists gradually easing open in her lap. Mrs. Garcia spoke hesitantly. "Your life seems rather precarious at the moment."

Francesca thought of Clare, of the ugly rooms above the garage, of the string guitar, of her inability to call Dallie for help, even when she desperately needed it. "It is precarious," she agreed. Leaning over, she picked up her canvas shoulder bag. Then she rose from her chair. The impulsive, optimistic part of her that she thought had died months before seemed to have taken over her feet, seemed to be forcing her to do something that could only lead to disaster, something illogical, foolish…

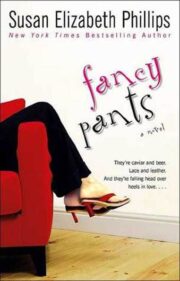

"Fancy Pants" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Fancy Pants". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Fancy Pants" друзьям в соцсетях.