“As to eligibility, ma’am,” said Ravenscar, through his teeth, “I apprehend that Ormskirk has plans for your future which should answer the purpose admirably!”

The palm of Miss Grantham’s hand itched again to hit him, and it was with an immense effort of will that she forced herself to refrain. She replied with scarcely a tremor to betray her indignation, “But even you must realize, sir, that Lord Ormskirk’s obliging offer is not to be thought of beside your cousin’s proposal. I declare, I have a great fancy to become Lady Mablethorpe.”

“I don’t doubt it!” he said harshly. “By God, if I had my way, women of your stamp should be whipped at the cart’s tail!”

“Why, how fierce you are!” she marvelled. “And all because I have a desire to turn respectable! I dare say I shall make Adrian a famous wife.”

“A wife out of a gaming-house!” he ejaculated. “One of faro’s daughters! You forget, ma’am, that I have been privileged to observe you in your proper milieu! Do you imagine that I will permit the young fool to ruin himself by marriage with you? You’ll learn to know me better!”

She shrugged. “This is mere ranting, Mr Ravenscar. It would be well if you learned to know me better.”

“God forbid!” he said with a snap. “I have learnt enough this morning to assure me that no greater disaster could befall my cousin than to find himself tied to you!”

“And is ten thousand pounds all you are prepared to offer to save your cousin from this horrid fate?” she inquired.

He looked at her in a measuring way, as though he were appraising her worth. “It would be interesting to know what figure you set upon yourself, Miss Grantham.”

She appeared to give this matter her consideration. “I do not know. You regard the affair in so serious a light that I feel I should be very green to accept less than twenty thousand.”

He turned his horses, and they broke into a trot again. “Why stop at that?” he asked, with a short bark of laughter.

“Indeed, I dare say I shan’t,” said Miss Grantham cordially. “My price will rise as Adrian’s birthday approaches.”

He drove on in silence for some little way, frowning heavily at the road ahead.

“How pretty the trees are, with their leaves just on the turn!” remarked Miss Grantham, in soulful accents.

He paid no heed to this sally, but once more looked down at her. “If I engage to pay you twenty thousand pounds, will you release my cousin?” he asked abruptly.

Miss Grantham tilted her head on one side. “I own, twenty thousand pounds is a temptation,” she said. “And yet ...!” she added undecidedly. “No, I think I would prefer to marry Adrian.”

“You will regret that decision, ma’am,” he said, dropping his hands, and letting the greys shoot.

“Oh, I trust not, sir! After all, Adrian is a most amiable young man, and I shall enjoy being his wife, and having a great deal of pin-money. I hope,” she added graciously, “that you will be one of our first guests at Mablethorpe. You will see then what a fine ladyship I mean to be.”

He vouchsafed no answer to this, so after a thoughtful pause she said airily: “Of course, there will be a good many changes to be made at Mablethorpe before I shall be ready to receive visitors. I collect that everything is shockingly old fashioned there. The London house too! But I have a great turn for furnishing houses, and I do not despair of achieving something very tolerable.”

The contemptuous curl of Mr Ravenscar’s mouth was all the sign he gave of having heard this speech.

“I mean to set up a faro-bank of my own,” pursued Miss Grantham. “It will be very select, of course: admission only by card. To make a success of that sort of thing, one must have a certain position in the world, and that Adrian can give me. I will wager that my card-parties become the rage within a twelvemonth!”

“If you think, ma’am, to force up the price by these disclosures, you are wasting your time!” said Ravenscar. “Your plans for the future come as no surprise to me.” He reined in his horses to a more sober pace, as the gates of the Park came into sight. “You have had the chance to enrich yourself, and you have seen fit to refuse it. My offer is no longer open to your acceptance.”

She was surprised, but took care not to let it appear. “Why, now you talk like a sensible man, sir!” she said. “You accept the inevitable, in fact.”

They passed through the gates, and turned eastwards, bowling along with a disregard for the convenience of all other traffic which drew curses from two porters, a hackney-coachman, and a portly old gentleman who was unwise enough to try to cross the street ahead of the curricle. “No,” said Ravenscar. “Once more you are out in your reckoning, Miss Grantham. You have chosen to cross swords with me, and you shall see how you like it. Let me tell you that it was with the greatest reluctance that I made my offer! It goes much against the grain with me to enrich harpies!” He glanced down at her as he spoke, and encountered such a blaze of anger in her eyes that he was momentarily taken aback. But even as his brows snapped together in quick suspicion, the long-lashed lids had veiled her eyes, and she was laughing.

The rest of the drive back to St James’s Square was accomplished in silence. When the curricle drew up outside her door, Miss Grantham put back the rug that covered her knees, and said with deceptive affability: “A most enjoyable drive, Mr Ravenscar. I must thank you for having given me the opportunity to make your better acquaintance. I fancy we have both of us learnt something this morning.”

“Can you get down without my assistance?” he asked brusquely. “I am unable to leave the horses.”

“Certainly,” she replied, nimbly descending from the high carriage. “Goodbye, sir—or should I say au revoir?”

He slightly raised his hat. “Au revoir, ma’am!” he said, and drove on.

The door of the house was opened to Miss Grantham by Silas Wantage, who took one look at her flushed countenance, and said indulgently: “Now, what’s happened to put you into one of your tantrums, Miss Deb?”

“I am not in a tantrum!” replied Deborah furiously. “And if Lord Mablethorpe should call, I will see him!”

“Well, that’s a good thing,” said Wantage. “For he’s been here once already, and means to come again. I never saw anything like it, not in all my puff!”

“I wish you will not talk in that odiously vulgar way!” said Deborah.

“Not in a tantrum: oh, no!” said Mr Wantage, shaking his head. “And me that’s known you from your cradle! Your aunt says as how Master Kit’s a coming home on leave. What do you say to that?”

Miss Grantham, however, had nothing to say to it. She was an extremely fond sister, but for the moment the iniquities of Mr Ravenscar possessed her mind to the exclusion of all other interests. She ran upstairs to the little back-parlour on the half-landing, which was used as a morning-room. Lady Bellingham was writing letters there, at a spindle-legged table in the window. She looked up as her niece entered the room, and cried: “Well, my love, so you are back already! Tell me at once, did—” She broke off, as her eyes met Miss Grantham’s stormy ones. “Oh dear!” she said, in a dismayed voice. “What has happened?”

Miss Grantham untied her bonnet-strings with a savage jerk, and cast the bonnet on to a chair. “He is the vilest, rudest, stupidest, horridest man alive! Oh, but I will serve him out for this! I will make him sorry he ever dared—I’ll have no mercy on him! He shall grovel to me! Oh, I am in such a rage.”

“Yes, my love, I can see you are,” said her aunt faintly. “Did he—did he make love to you?”

“Love!” exclaimed Miss Grantham. “No, indeed! My thoughts did not lie in that direction! I am a harpy, if you please, Aunt Lizzie! Women like me should be whipped at the cart’s tail!”

“Good heavens, Deb, is the man out of his senses?” demanded Lady Bellingham.

“By no means! He is merely stupid, and rude, and altogether abominable! I hate him! I wish I might never set eyes on him again!”

“But what did he do?” asked Lady Bellingham bewildered.

Miss Grantham ground her white teeth. “He came to rescue his precious cousin from my toils! That was why he invited me to drive out with him. To insult me!”

“Oh dear, you thought it might be that!” said her aunt sadly.

Miss Grantham paid no heed to this interruption. “A Grantham is not a fit bride for Lord Mablethorpe! To marry me would be to ruin himself! Oh, I could scream with vexation!”

Lady Bellingham regarded her doubtfully. “But you said much yourself, my dear. I remember distinctly—”

“It doesn’t signify in the least,” said Miss Grantham. “He hi no right to say it”

Lady Bellingham agreed to this wholeheartedly, after watching her niece pace round the room for several minutes, ventured to inquire what had happened during the course of the drive. Miss Grantham stopped dead her tracks, and replied in a shaking voice: “He tried to bribe me!”

“Tried to bribe you not to marry Adrian, Deb?” asked her aunt. “But how very odd of him, when you had never the lea intention of doing so! What can have put such a notion in his head?”

“I am sure I don’t know, and certainly I don’t care a fig replied Deborah untruthfully. “He had the insolence to offer me five thousand pounds if I would relinquish my pretensions—my pretensions!—to Adrian’s hand and heart!”

Lady Bellingham, over whose plump countenance a hopeful expression had begun to creep, looked disappointed, she said: “Five thousand! I must say, Deb, I think that is shabby!”

“I said that I feared he was trying to trifle with me,” recounted Miss Grantham with relish.

“Well, and I am sure you could not have said anything better, my love! I declare, I did not think so meanly of him!”

“Then,” continued Miss Grantham, “he said he would double that figure.”

Lady Bellingham dropped her reticule. “Ten thousand!” she exclaimed faintly. “No, never mind my reticule, Deb, it don’t signify! What did you say to that?”

“I said, Paltry!” answered Miss Grantham.

Her aunt blinked at her. “Paltry ... Would you—would you call it paltry, my love?”

“I did call it paltry. I said I would not let Adrian slip through my fingers for a mere ten thousand. I enjoyed saying that, Aunt Lizzie!”

“Yes, my dear, but—but was it wise, do you think?”

“Pooh, what can he do, pray?” said Miss Grantham scornfully. “To be sure, he flew into as black a temper as my own, and took no pains to conceal it from me. I was excessively glad to see him so angry! He said—about Ormskirk—Oh, if I were a man, to be able to call him out, and run him through, and through, and through!”

Lady Bellingham, who appeared quite shattered, said feebly that you could not run a man through three times. “At least, I don’t think so,” she added. “Of course, I never was present at a duel, but there are always seconds, you know, and they would be bound to stop you.”

“Nobody would stop me!” declared Miss Grantham bloodthirstily. “I would like to carve him into mincemeat!”

“Oh dear, I can’t think where you get such unladylike notions!” sighed her aunt. “I do trust that you did not say it?”

“No, I said that I thought I should make Adrian a famous wife. That made him angrier than ever. I thought he might very likely strangle me. However, he did not. He asked me what figure I set upon myself.”

Lady Bellingham showed a flicker of hope. “And what answer did you make to that, Deb?”

“I said I should be very green to accept less than twenty thousand!”

“Less than—My love, where are my smelling-salts? I do not feel at all the thing! Twenty thousand! It is a fortune! He must have thought you had taken leave of your senses!”

“Very likely, but he said he would pay me twenty thousand if I would release Adrian.”

Lady Bellingham sank back in her chair, holding the vinaigrette to her nose.

“So then,” concluded Miss Grantham, with reminiscent pleasure, “I said that after all I preferred to marry Adrian.”

A moan from her aunt brought her eyes round to that afflicted lady. “Mablethorpe instead of twenty thousand pounds?” demanded her ladyship, in quavering accents. “But you told me positively you would not have him!”

“Of course I shall not!” said Miss Grantham impatiently. “At least, not unless I marry him in a fit of temper,” she added, with an irrepressible twinkle.

“Deb, either you are mad, or I am!” announced Lady Bellingham, lowering the vinaigrette. “Oh, it does not beat thinking of! We might have been free of all our difficulties! Ring the bell; I must have the hartshorn!”

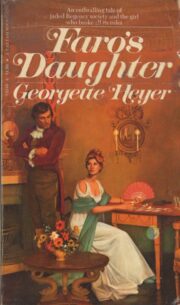

"Faro’s Daughter" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Faro’s Daughter". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Faro’s Daughter" друзьям в соцсетях.