“Judging from the style of the establishment, her notions of an adequate recompense are not likely to jump with mine,” said Mr Ravenscar.

“But appearances are so often deceptive,” said his lordship sweetly. “The aunt—an admirable woman, of course!—is not, alas, blessed with those qualities which distinguish other ladies in the same profession. Her ideas, which are charmingly lavish, preclude the possibility of the house’s being run at a profit, in the vulgar phrase. In a word, my dear Ravenscar, her ladyship is badly dipped.”

“No doubt you are in a position to know?” said Mr Ravenscar.

“None better,” replied Ormskirk. “I hold a mortgage or the house, you see. And in one of those moments of generosity, with which you are doubtless familiar, I—ah—acquired some of the more pressing of her ladyship’s debts.”

“That,” said Mr Ravenscar, “is not a form of generosity with which I have ever yet been afflicted.”

“I regarded it in the light of an investment,” explained his lordship. “Speculative, of course, but not, I thought, without promise of a rich return.”

“If you hold bills of Lady Bellingham’s, you don’t appear to me to stand in need of any assistance from me,” said Mr Ravenscar bluntly. “Use ’em!”

A note of pain crept into his lordship’s smooth voice. “My dear fellow! I fear we are no longer seeing eye to eye Consider, if you please, for an instant! You will appreciate, am sure, the vast difference that lies between the surrender: from—shall we say gratitude?—and the surrender to—we shall be obliged to say force majeure.”

“In either event you stand in the position of a scoundrel,” retorted Mr Ravenscar. “I prefer the more direct approach.”

“But one is, unhappily for oneself, a gentleman,” Ormskirk pointed out. “It is unfortunate, and occasionally tiresome, but one is bound to remember that one is a gentleman.”

“Let me understand you, Ormskirk!” said Mr Ravenscar. “Your sense of honour being too nice to permit of your holding the girl’s debts over her by way of threat, or bribe, or what you will, it yet appears to you expedient that someone else—myself, for example—should turn the thumbscrew for you?”

Lord Ormskirk walked on several paces beside Mr Ravenscar before replying austerely: “I have frequently deplored a tendency in these days to employ in polite conversation a certain crudity, a violence, which is offensive to persons of my generation. You, Ravenscar, prefer the fists to the sword. With me it is otherwise. Believe me, it is always a mistake to put too much into words.”

“It doesn’t sound well in plain English, does it?” retorted Ravenscar. “Let me set your mind at rest! My cousin will not marry Miss Grantham.”

His lordship sighed. “I feel sure I can rely on you, my dear fellow. There is positively no need for us to pursue the subject further. So you played a hand or two at piquet with the divine Deborah! They tell me your skill at the game is remarkable. But you play at Brooks’s, I fancy. Such a mausoleum! I wonder you will go there. You must do me the honour of dining at my house one evening, and of giving me the opportunity to test your skill. I am considered not inexpert myself, you know.”

They had reached Grosvenor Square by this time, where his lordship’s house was also situated. Outside it, Ormskirk halted, and said pensively: “By the way, my dear Ravenscar, did you know that Filey has acquired the prettiest pair of blood-chestnuts it has ever been my lot to clap eyes on?”

“No,” said Mr Ravenscar indifferently. “I supposed him to have bought a better pair than he set up against my greys six months ago.”

“What admirable sang-froid you have!” remarked his lordship. “I find it delightful, quite delightful! So you actually backed yourself to win without having seen the pair you were to be matched with!”

“I know nothing of Filey’s horses,” Ravenscar responded. “It was quite enough to have driven against him once, however, to know him for a damnably cow-handed driver.”

His lordship laughed gently. “Almost you persuade me to bet on you, my dear Ravenscar! I recall that your father was a notable whip.”

“He was, wasn’t he?” said Mr Ravenscar. “If Filey’s pair are all you say, you will no doubt be offered very good odds.” He raised his hat as he spoke, nodded a brief farewell, and passed on towards his own house, at the other end of the square.

He was finishing his breakfast, several hours later, when Lord Mablethorpe was announced. Coffee, small-ale, the remains of a sirloin, and a ham still stood upon the table, and bore mute witness to the fact that Mr Ravenscar was a good trencherman. Lord Mablethorpe, who was looking a trifle heavy-eyed, grimaced at the array, and said: “How you can, Max-! And you ate supper at one o’clock!”

Mr Ravenscar, who was dressed only in his shirt and breeches, with a barbaric-looking brocade dressing-gown over all, waved a hand towards a chair opposite to him. “Sit down and have some ale, or some coffee, or whatever it is you drink at this hour.” He transferred his attention to his major-domo who was standing beside his chair. “Mrs Ravenscar’s room to be prepared, then, and you had better tell Mrs Dove to make the Blue Room ready for Miss Arabella. I believe she took, fancy to it when she was last here. And take the dustsheets of the chairs in the drawing-room! If there is anything else, you will probably know of it better than I”

“Oh, are Aunt Olivia and Arabella coming to town?” asked Adrian. “That’s famous! I haven’t seen Arabella for months. When do they arrive?”

“Today, according to my latest information. Come and dine.”

“I can’t tonight,” Adrian said, his ready blush betraying him. “But tell Arabella I shall pay her a morning-call immediately!”

Mr Ravenscar gave a grunt, nodded dismissal to his major domo, and poured himself out another tankard of ale. With this in his hand, he lay back in his chair, looking down the table at his cousin’s ingenuous countenance. “Well, if you won’t come to dine tonight, come to Vauxhall Gardens tomorrow,” he suggested. “I shall be escorting Arabella and Olivia there. There’s a ridotto, or some such foolery.”

“Oh, thank you! Yes, indeed I should like it of all things That is, if—but I don’t suppose—” He stopped, looking a little, self-conscious. “I am glad I have found you at home,” he said. “I particularly wanted to see you!”

“What is it?” Ravenscar asked.

“As a matter of fact, I came to ask your advice!” replied Adrian, in a rush. “At least, no, not that exactly,—for my mind is quite made up! But the thing is that my mother depends a good deal upon your judgement; and you’ve always been devilish good to me, so I thought I would tell you how things stand.”

There was nothing Mr Ravenscar wanted less than to hear his cousin explain his passion for Miss Grantham, but he said: “By all means! Are you coming to watch my race, by the way?”

This question succeeded in diverting Lord Mablethorpe for the moment, and he replied, with his face lighting up: “Oh, by Jove, I should think I am! But what a complete hand you are, Max! I never heard you make such a bet in your life! I suppose you will win. There is no one like you when it comes to handling the ribbons! Where will it be run?”

“Oh, down at Epsom, I imagine! I left it to Filey to settle the locality.”

“I hate that fellow!” said Lord Mablethorpe, frowning. “I hope you will beat him.”

“Well, I shall do my best. Do you go to Newmarket next month?”

“Yes. No. That is, I am not sure. But I didn’t come to talk of that!”

Mr Ravenscar resigned himself to the inevitable, made himself comfortable in his chair, and said: “What did you come to talk of?”

Lord Mablethorpe picked up a fork, and began to trace patterns with it upon the table. “I hadn’t the intention of telling you about it,” he confessed. “It is not as though you were my guardian, after all! Of course, I know you are one of my trustees, but that is quite a different thing, isn’t it?”

“Oh, quite!” agreed Ravenscar.

“I mean, you are not responsible for anything I may do,” said Adrian, pressing home his point with a little anxiety.

“Not a bit.”

“In any event, I shall come of age in a couple of months. It is really no concern of anyone.”

“None at all,” said Ravenscar, betraying no trace of the uneasiness his relative evidently expected him to feel. “In fact, you may just as well keep your own counsel, and have some ale.”

“No, I don’t want any,” said Adrian, rather impatiently. “As I said, I had no intention of telling you. Only you happened to visit—to visit Lady Bel’s house last night, and—and you met Her.”

“I did not exchange more than half a dozen words with Lady Bellingham, however.”

“Not Lady Bellingham!” said Adrian, irritated by such stupidity. “I mean Miss Grantham!”

“Oh, Miss Grantham! Yes, I played piquet with her, certainly. What of it?”

“What did you think of her, Max?” asked his lordship shyly.

“Really, I don’t remember that I thought about her at all. Why?”

Adrian looked up indignantly. “Good God, you surely must at least have seen how—how very beautiful she is!”

“Why, yes, I suppose she is tolerably handsome!” conceded Ravenscar.

“Tolerably handsome!” ejaculated Adrian, in dumbfounded accents.

“Yes, certainly, for one who is not in the first blush of youth A little too strapping for my taste, and will probably put or flesh in middle age, but I will allow her to be a well-looking woman.”

Adrian laid down the fork, and said, with a considerable heightened colour: “I had better make it plain to you at once Max, that—that I mean to marry her!”

“Marry Miss Grantham?” said Ravenscar, raising his brows. “My dear boy, why?”

This unemotional way of receiving startling tidings was damping in the extreme to a young gentleman who had braced himself to encounter violent opposition, and for a moment Adrian seemed to be at a loss to know what to say. After a slight pause, he said with immense dignity: “I love her.”

“How very odd!” said Ravenscar, apparently puzzled.

“I see nothing odd in it!”

“No, of course not. How should you, indeed? But surely someone nearer your own age-?”

“The difference in our ages doesn’t signify in the least. You talk as though Deb were in her thirties!”

“I beg pardon.”

Adrian eyed him with considerable resentment. “My mind is irrevocably made up, Max. I shall never love another woman I knew as soon as I saw her that she was the only one in the world for me! Of course, I don’t expect you to understand that, because you are the coldest fellow—well, I mean, you have never been in love!”

Ravenscar laughed.

“Well, not in the way I mean,” amended his lordship.

“Evidently not. But what has all this to do with me?”

“Nothing at all!” replied Adrian, with emphasis. “Only that since you have met Deb I thought I would tell you. I do not wish to do anything secretly. I am not in the least ashamed of loving Deb!”

“It would be very odd if you were,” commented Ravenscar. “I apprehend that Miss Grantham has accepted your offer??

“Well, not precisely,” Adrian confessed. “That is, she will marry me, I know, but she is the most delightfully teasing creature-! Oh, I can’t tell you, but when you know her better you will see for yourself!”

Ravenscar set down his tankard. “When you say “not precisely”, what do you mean?”

“Oh, she says I must wait until I come of age before I make up my mind—as though I could ever change it! She did not wish me to say anything about it yet, but someone told my mother that I was entangled—entangled!—by her and so it all came out. And that is “in part” why I have come to you, Max.”

“Oh?”

“My mother will listen to you,” said Adrian confidently. “You see, she has taken an absurd notion into her head that Deb is not good enough for me. Of course, I know that her being in Lady Bel’s house is a most unfortunate circumstance, but she is not in the least the sort of girl you might imagine, Max, upon my word she is not! She don’t even like cards above a little! It is all to help her aunt.”

“Did she tell you so?”

“Oh no, it was Kennet who told me! He has known her since her childhood. Really, Max, she is the dearest, sweetest—oh, there are no words to describe her!”

Mr Ravenscar could have found several, but refrained.

“She is not like any other woman I have ever met,” pursued his lordship. “I wonder that you were not struck by it!”

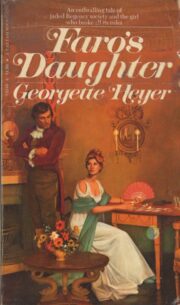

"Faro’s Daughter" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Faro’s Daughter". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Faro’s Daughter" друзьям в соцсетях.