Then my brothers started trapping the mice, which I thought was just to help out. I didn’t suspect a thing until the day I heard my mother screaming from the depths of their room. They were, it turns out, raising a boa constrictor.

Mom’s foot came down in a big way, and I thought she was going to throw us out, lock, stock, and boa, but then I made the most amazing discovery—chickens lay eggs! Beautiful, shiny, creamy white eggs! I first found one under Bonnie, then Clyde—whom I immediately renamed Clydette—and one more in Florence’s bed. Eggs!

I raced inside to show my mom, and after a brief moment of blinking at them, she withered into a chair. “No,” she whimpered. “No more chicks!”

“They’re not chicks, Mom… they’re eggs!”

She was still looking quite pale, so I sat in the chair next to her and said, “We don’t have a rooster… ?”

“Oh.” The color was coming back to her cheeks. “Is that so?”

“I’ve never heard a cock-a-doodle-do, have you?”

She laughed. “A blessing I guess I’ve forgotten to count.” She sat up a little and took an egg from my palm. “Eggs, huh. How many do you suppose they’ll lay?”

“I have no idea.”

As it turns out, my hens laid more eggs than we could eat. At first we tried to keep up, but soon we were tired of boiling and pickling and deviling, and my mother started complaining that all these free eggs were costing her way too much.

Then one afternoon as I was collecting eggs, our neighbor Mrs. Stueby leaned over the side fence and said, “If you ever have any extra, I’d be happy to buy them from you.”

“Really?” I asked.

“Most certainly. Nothing quite like free-range eggs. Two dollars a dozen sound fair to you?”

Two dollars a dozen! I laughed and said, “Sure!”

“Okay, then. Whenever you have some extras, just bring ’em over. Mrs. Helms and I got to discussing it last night on the phone, but I asked you first, so make sure you offer ’em up to me before her, okay, Juli?”

“Sure thing, Mrs. Stueby!”

Between Mrs. Stueby and Mrs. Helms three doors down, my egg overflow problem was solved. And maybe I should’ve turned the money over to my mother as payment for having destroyed the backyard, but one “Nonsense, Julianna. It’s yours,” was all it took for me to start squirreling it away.

Then one day as I was walking down to Mrs. Helms’ house, Mrs. Loski drove by. She waved and smiled, and I realized with a pang of guilt that I wasn’t being very neighborly about my eggs. She didn’t know that Mrs. Helms and Mrs. Stueby were paying me for these eggs. She probably thought I was delivering them out of the kindness of my heart.

And maybe I should’ve been giving the eggs away, but I’d never had a steady income before. Allowance at our house is a hit-or-miss sort of thing. Usually a miss. And earning money from my eggs gave me this secret happy feeling, which I was reluctant to have the kindness of my heart encroach upon.

But the more I thought about it, the more I realized that Mrs. Loski deserved some free eggs. She had been a good neighbor to us, lending us supplies when we ran out unexpectedly and being late to work herself when my mother needed a ride because our car wouldn’t start. A few eggs now and again… it was the least I could do.

There was also the decidedly blissful possibility of running into Bryce. And in the chilly sparkle of a new day, Bryce’s eyes seemed bluer than ever. The way he looked at me—the smile, the blush—it was a Bryce I didn’t get to see at school. The Bryce at school was way more protected.

By the third time I brought eggs over to the Loskis, I realized that Bryce was waiting for me. Waiting to pull the door open and say, “Thanks, Juli,” and then, “See you at school.”

It was worth it. Even after Mrs. Helms and Mrs. Stueby offered me more money per dozen, it was still worth it. So, through the rest of sixth grade, through all of seventh grade and most of eighth, I delivered eggs to the Loskis. The very best, shiniest eggs went straight to the Loskis, and in return I got a few moments alone with the world’s most dazzling eyes.

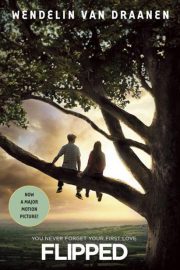

"Flipped" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Flipped". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Flipped" друзьям в соцсетях.