“Well, then… ”

He leaned forward even farther and whispered, “You did.”

“I did?”

He nodded. “Twice.”

“But… ”

“The doctor who delivered you was on the ball, plus apparently there was some slack in the cord, so he was able to loop it off as you came out. You didn’t hang yourself coming into the world, but it could very easily have gone the other way.”

If I’d been told years or even weeks ago that I’d come down the chute noosed and ready to hang, I’d have made some kind of joke about it, or more likely I’d have said, Yeah, that’s nice; now can you spare me the discussion?

But after everything that had happened, I was really freaking out, and I couldn’t escape the questions tidal-waving my brain. Where would I be if things had been different? What would they have done with me? From the way my dad was talking, he wouldn’t have had much use for me, that’s for sure. He’d have stuck me in a nuthouse somewhere, any where, and forgotten about me. But then I thought, No! I’m his kid. He wouldn’t do that… would he?

I looked around at everything we had — the big house, the white carpet, the antiques and artwork and stuff that was everywhere. Would they have given up all the stuff to make my life more pleasant?

I doubted it, and man, I doubted it big-time. I’d have been an embarrassment. Something to try to forget about. How things looked had always been a biggie to my parents. Especially to my dad.

Very quietly my granddad said, “You can’t dwell on what might have been, Bryce.” Then, like he could read my mind, he added, “And it’s not fair to condemn him for something he hasn’t done.”

I nodded and tried to get a grip, but I wasn’t doing a very good job of it. Then he said, “By the way, I appreciated your comment before.”

“What?” I asked, but my throat was feeling all pinched and swollen.

“About your grandmother. How did you know that?”

I shook my head and said, “Juli told me.”

“Oh? You spoke with her, then?”

“Yeah. Actually, I apologized to her.”

“Well…!”

“And I was feeling a lot better about everything, but now… God, I feel like such a jerk again.”

“Don’t. You apologized, and that’s what matters.” He stood up and said, “Say, I’m in the mood for a walk. Want to join me?”

Go for a walk? What I wanted to do was go to my room, lock the door, and be left alone.

“I find it really helps to clear the mind,” he said, and that’s when I realized that this wasn’t just a walk — this was an invitation to do something together.

I stood up and said, “Yeah. Let’s get out of here.”

For a guy who’d only basically ever said Pass the salt to me, my granddad turned out to be a real talker. We walked our neighborhood and the next neighborhood and the next neighborhood, and not only did I find out that my granddad knows a lot of stuff, I found out that the guy is funny. In a subtle kind of dry way. It’s the stuff he says, plus the way he says it. It’s really, I don’t know, cool.

As we were winding back into our own territory, we passed by the house that’s going up where the sycamore tree used to be. My granddad stopped, looked up into the night, and said, “It must’ve been a spectacular view.”

I looked up, too, and noticed for the first time that night that you could see the stars. “Did you ever see her up there?” I asked him.

“Your mother pointed her out to me one time as we drove by. It scared me to see her up so high, but after I read the article I understood why she did it.” He shook his head. “The tree’s gone, but she’s still got the spark it gave her. Know what I mean?”

Luckily I didn’t have to answer. He just grinned and said, “Some of us get dipped in flat, some in satin, some in gloss….” He turned to me. “But every once in a while you find someone who’s iridescent, and when you do, nothing will ever compare.”

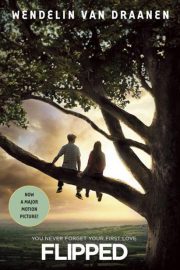

"Flipped" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Flipped". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Flipped" друзьям в соцсетях.