What happened after that is a bit of a blur. I remember the neighbors gathering, and the police with megaphones. I remember the fire brigade, and some guy saying it was his blasted tree and I’d darn well better get out of it.

Somebody tracked down my mother, who cried and pleaded and acted not at all the way a sensible mother should, but I was not coming down. I was not coming down.

Then my father came racing up. He jumped out of his pickup truck, and after talking with my mother for a few minutes, he got the guy in the cherry picker to give him a lift up to where I was. After that it was all over. I started crying and tried to get him to look out over the rooftops, but he wouldn’t. He said that no view was worth his little girl’s safety.

He got me down and he took me home, only I couldn’t stay there. I couldn’t stand the sound of chain saws in the distance.

So Dad took me with him to work, and while he put up a block wall, I sat in his truck and cried.

I must’ve cried for two weeks straight. Oh, sure, I went to school and I functioned the best I could, but I didn’t go there on the bus. I started riding my bike instead, taking the long way so I wouldn’t have to go up to Collier Street. Up to a pile of sawdust that used to be the earth’s most magnificent sycamore tree.

Then one evening when I was locked up in my room, my father came in with something under a towel. I could tell it was a painting because that’s how he transports the important ones when he shows them in the park. He sat down, resting the painting on the floor in front of him. “I always liked that tree of yours,” he said. “Even before you told me about it.”

“Oh, Dad, it’s okay. I’ll get over it.”

“No, Julianna. No, you won’t.”

I started crying. “It was just a tree….”

“I never want you to convince yourself of that. You and I both know it isn’t true.”

“But Dad… ”

“Bear with me a minute, would you?” He took a deep breath. “I want the spirit of that tree to be with you always. I want you to remember how you felt when you were up there.” He hesitated a moment, then handed me the painting. “So I made this for you.”

I pulled off the towel, and there was my tree. My beautiful, majestic sycamore tree. Through the branches he’d painted the fire of sunrise, and it seemed to me I could feel the wind. And way up in the tree was a tiny girl looking off into the distance, her cheeks flushed with wind. With joy. With magic.

“Don’t cry, Julianna. I want it to help you, not hurt you.” I wiped the tears from my cheeks and gave a mighty sniff. “Thank you, Daddy,” I choked out. “Thank you.”

I hung the painting across the room from my bed. It’s the first thing I see every morning and the last thing I see every night. And now that I can look at it without crying, I see more than the tree and what being up in its branches meant to me.

I see the day that my view of things around me started changing.

Bryce: Brawk-Brawk-Brawk!

Eggs scare me. Chickens, too. And buddy, you can laugh at that all you want, but I’m being dead serious here.

It started in the sixth grade with eggs.

And a snake.

And the Baker brothers.

The Baker brothers’ names are Matt and Mike, but even now I can’t tell you which one’s which. You never see one without the other. And even though they’re not twins, they do look and sound pretty much the same, and they’re both in Lynetta’s class, so maybe one of them got held back.

Although I can’t exactly see a teacher voluntarily having either of those maniacs two years in a row.

Regardless, Matt and Mike are the ones who taught me that snakes eat eggs. And when I say they eat eggs, I’m talking they eat them raw and shell-on whole.

I probably would’ve gone my entire life without this little bit of reptilian trivia if it hadn’t been for Lynetta. Lynetta had this major-league thing for Skyler Brown, who lives about three blocks down, and every chance she got, she went down there to hang out while he practiced the drums. Well, boom-boom-whap, what did I care, right? But then Skyler and Juli’s brothers formed a band, which they named Mystery Pisser.

When my mom heard about it, she completely wigged out. “What kind of parents would allow their children to be in a band named Mystery Pisser? It’s vile. It’s disgusting!”

“That’s the whole point, Mom,” Lynetta tried to explain. “It doesn’t mean anything. It’s just to get a rise out of old people.”

“Are you calling me old, young lady? Because it’s certainly getting a rise out of me!”

Lynetta just shrugged, implying that my mom could draw her own conclusion.

“Go! Go to your room,” my mother snapped.

“For what?” Lynetta snapped back. “I didn’t say a thing!”

“You know perfectly well what for. Now you go in there and adjust your attitude, young lady!”

So Lynetta got another one of her teenage time-outs, and after that any time Lynetta was two minutes late coming home for dinner, my mother would messenger me down to Skyler’s house to drag her home. It might have been embarrassing for Lynetta, but it was worse for me. I was still in elementary school, and the Mystery Pisser guys were in high school. They were ripe and ragged, raging power chords through the neighborhood, while I looked like I’d just gotten back from Sunday school.

I’d get so nervous going down there that my voice would squeak when I’d tell Lynetta it was time for dinner. It literally squeaked. But after a while the band dropped Mystery from their name, and Pisser and its entourage got used to me showing up. And instead of glaring at me, they started saying stuff like, “Hey, baby brother, come on in!” “Hey, Brycie boy, wanna jam?”

This, then, is how I wound up in Skyler Brown’s garage, surrounded by high school kids, watching a boa constrictor swallow eggs. Since I’d already seen it down a rat in the Baker brothers’ bedroom, Pisser had lost at least some of the element of surprise. Plus, I picked up on the fact that they’d been saving this little show to freak me out, and I really didn’t want to give them the satisfaction.

This wasn’t easy, though, because watching a snake swallow an egg is actually much creepier than you might think. The boa opened its mouth to an enormous size, then just took the egg in and glub! We could see it roll down its throat.

But that wasn’t all. After the snake had glubbed down three eggs, Matt-or-Mike said, “So, Brycie boy, how’s he gonna digest those?”

I shrugged and tried not to squeak when I answered, “Stomach acid?”

He shook his head and pretended to confide, “He needs a tree. Or a leg.” He grinned at me. “Wanna volunteer yours?”

I backed away a little. I could just see that monster try to swallow my leg whole as an after-egg chaser. “N-no!”

He laughed and pointed at the boa slithering across the room. “Aw, too bad. He’s going the other way. He’s gonna use the piano instead!”

The piano! What kind of snake was this? How could my sister stand being in the same room as these dementos? I looked at her, and even though she was pretending to be cool with the snake, I know Lynetta — she was totally creeped out by it.

The snake wrapped itself around the piano leg about three times, and then Matt-or-Mike put his hands up and said, “Shhh! Shhh! Everybody quiet. Here goes!”

The snake stopped moving, then flexed. And as it flexed, we could hear the eggs crunch inside him. “Oh, gross!” the girls wailed. “Whoa, dude!” the guys all said. Mike and Matt smiled at each other real big and said, “Dinner is served!”

I tried to act cool about the snake, but the truth is I started having bad dreams about the thing swallowing eggs. And rats. And cats.

And me.

Then the real-life nightmare began.

One morning about two weeks after the boa show in Skyler’s garage, Juli appears on our doorstep, and what’s she got in her hands? A half-carton of eggs. She bounces around like it’s Christmas, saying, “Hiya, Bryce! Remember Abby and Bonnie and Clyde and Dexter? Eunice and Florence?”

I just stared at her. Somehow I remembered Santa’s reindeer a little different than that.

“You know… my chickens? The ones I hatched for the science fair last year?”

“Oh, right. How could I forget.”

“They’re laying eggs!” She pushed the carton into my hands. “Here, take these! They’re for you and your family.”

“Oh. Uh, thanks,” I said, and closed the door.

I used to really like eggs. Especially scrambled, with bacon or sausage. But even without the little snake incident, I knew that no matter what you did to these eggs, they would taste nothing but foul to me. These eggs came from the chickens that had been the chicks that had hatched from the eggs that had been incubated by Juli Baker for our fifth-grade science fair.

It was classic Juli. She totally dominated the fair, and get this — her project was all about watching eggs. My friend, there is not a lot of action to report on when you’re incubating eggs. You’ve got your light, you’ve got your container, you’ve got some shredded newspaper, and that’s it. You’re done.

Juli, though, managed to write an inch-thick report, plus she made diagrams and charts — I’m talking line charts and bar charts and pie charts — about the activity of eggs. Eggs!

She also managed to time the eggs so that they’d hatch the night of the fair. How does a person do that? Here I’ve got a live-action erupting volcano that I’ve worked pretty stinking hard on, and all anybody cares about is Juli’s chicks pecking out of their shells. I even went over to take a look for myself, and — I’m being completely objective here — it was boring. They pecked for about five seconds, then just lay there for five minutes.

I got to hear Juli jabber away to the judges, too. She had a pointer — can you believe that? Not a pencil, an actual retractable pointer, so she could reach across her incubator and tap on this chart or that diagram as she explained the excitement of watching eggs grow for twenty-one days. The only thing she could’ve done to be more overboard was put on a chicken costume, and buddy, I’m convinced — if she’d thought of it, she would have done it.

But hey — I was over it. It was just Juli being Juli, right? But all of a sudden there I am a year later, holding a carton of home-grown eggs. And I’m having a hard time not getting annoyed all over again about her stupid blue-ribbon project when my mother leans out from the hallway and says, “Who was that, honey? What have you got there? Eggs?”

I could tell by the look on her face that she was hot to scramble. “Yeah,” I said, and handed them to her. “But I’m having cereal.”

She opened the carton, then closed it with a smile. “How nice!” she said. “Who brought them over?”

“Juli. She grew them.”

“Grew them?”

“Well, her chickens did.”

“Oh?” Her smile started falling as she opened the carton again. “Is that so. I didn’t know she had… chickens.”

“Remember? You and Dad spent an hour watching them hatch at last year’s science fair?”

“Well, how do we know there’re not… chicks inside these eggs?”

I shrugged. “Like I said, I’m having cereal.”

We all had cereal, but what we talked about were eggs. My dad thought they’d be just fine — he’d had farm-fresh eggs when he was a kid and said they were delicious. My mother, though, couldn’t get past the idea that she might be cracking open a dead chick, and pretty soon discussion turned to the role of the rooster — something me and my Cheerios could’ve done without.

Finally Lynetta said, “If they had a rooster, don’t you think we’d know? Don’t you think the whole neighborhood would know?”

Hmmm, we all said, good point. But then my mom pipes up with, “Maybe they got it de-yodeled. You know — like they de-bark dogs?”

“A de-yodeled rooster,” my dad says, like it’s the most ridiculous thing he’s ever heard. Then he looks at my mom and realizes that he’d be way better off going along with her de-yodeled idea than making fun of her. “Hmmm,” he says, “I’ve never heard of such a thing, but maybe so.”

Lynetta shrugs and says to my mom, “So just ask them, why don’t you. Call up Mrs. Baker and ask her.”

“Oh,” my mom says. “Well, I’d hate to call her eggs into question. It doesn’t seem very polite, now, does it?”

“Just ask Matt or Mike,” I say to Lynetta.

She scowls at me and hisses, “Shut up.”

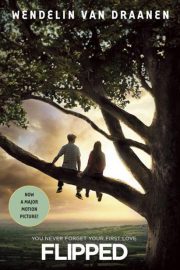

"Flipped" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Flipped". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Flipped" друзьям в соцсетях.