The next day Frances returned to him by messenger every gift she had ever received—the strand of pearls he had given her on St. Valentine’s day three years before, the wonderful bracelets and ear-rings and necklaces which had marked her birthdays and the Christmases or New Years. All of them came back, without even a note. Charles flung them into the fireplace.

That same morning Frances appeared unexpectedly in her Majesty’s apartments. She was covered from head to foot in a black-velvet cloak and she wore a vizard. Catherine and all her ladies looked toward the door in surprise as Frances removed the mask. For a moment she hesitated there and then all at once she ran forward, dropped to her knees, and taking up the hem of Catherine’s garment touched it to her lips. Catherine spoke quickly to her women, asking them to leave. They withdrew, to listen at the keyhole.

Then she reached down to touch the crown of Frances’s gleaming head and unexpectedly Frances burst into tears. She covered her face with her hands. “Oh, your Majesty! You must hate me! Can you ever forgive me?”

“Frances, my dear—you mustn’t cry so—you’ll make your head ache—Here, please—Look at me, poor child—” Catherine’s warm, soft voice still carried a trace of its Portuguese accent, which gave it an even greater tenderness, and now she placed one hand gently beneath Frances’s chin to raise her head.

Reluctantly Frances obeyed and for a moment they looked silently at each other. Then her sobs began again.

“I’m sorry, Frances,” said Catherine. “I’m sorry, for your sake.”

“Oh, it’s not for myself I’m crying!” protested Frances. “It’s for you! It’s for the unhappiness I’ve seen in your eyes sometimes when—” She stopped suddenly, shocked at her boldness, and then the words tumbled on hastily, as though she could undo in two minutes the wrongs her vanity had committed for years against this patient little woman.

“Oh, you must believe me, your Majesty! The only reason I’m going to get married is so that I may leave the Court! I’ve never meant to hurt you—never for a moment! But I’ve been vain and silly and thoughtless! I’ve made a fool of myself—but I’ve never wronged you, I swear I haven’t! He’s never been my lover—Oh, say you believe me—please say you believe me!”

She was holding Catherine’s hand hard against the beating pulse in her throat, and her head was thrown back as her eyes looked up with passionate, begging intensity. She had always liked Catherine, but she had never realized until now how deeply and humbly she admired her, nor how shameful her own behaviour had been. She had considered the Queen’s feelings no more than the crassest of Charles’s mistresses—no more than Barbara Palmer herself.

“I believe you, Frances. Any young girl would have been flattered. And you’ve always been kind and generous. You never used your power as a weapon to hurt others.”

“Oh, your Majesty! I didn’t! Truly I didn’t! I’ve never meant to hurt anyone! And your Majesty—I want you to know—I know you’ll believe me: Richmond had just come in. We were sitting talking. There’s never been anything indecent between us!”

“Of course there hasn’t, my dear.”

Frances slumped suddenly, her head dropped. “He’ll never believe me,” she said softly. “He has no faith—he doesn’t believe in anything.”

There were tears now in Catherine’s eyes and she shook her head slowly. “Perhaps he does, Frances. Perhaps he does, more than we think.”

Frances was tired now and despondent. She pressed her lips to the back of Catherine’s hand once more and got slowly to her feet. “I must go now, your Majesty.” They stood looking at each other, real tenderness and affection on both their faces. “I may never see you again—” Quickly and impulsively she kissed Catherine on the cheek, and then swirling about she rushed from the room. Catherine stood and watched her go, smiling a little, one hand lightly touching her face; the tears spilled off onto her bosom. Three days later Frances had left Whitehall—she eloped with the Duke of Richmond.

CHAPTER FORTY–EIGHT

IT WAS ON one cold rainy windy night in February that Buckingham, disguised in a black wig with his blonde eyebrows and mustache blackened, sat across the table from Dr. Heydon and watched the astrologer’s face as he consulted his charts of stars and moon, intersecting lines and geometrical figures. The room was lighted dimly by smoking tallow candles that smelt of frying fat, and the wind blew in gusts down the chimney, making their eyes burn and sending them into coughing fits.

“Pox on this damned weather!” muttered the Duke angrily, coughing and covering his nose and mouth with the long black riding-cloak he wore. And then as Heydon slowly raised his thin bony face he leaned anxiously across the table. “What is it! What do you find?”

“What I dare not speak of, your Grace.”

“Bah! What do I pay you for? Out with it!”

With an air of being forced against his better judgment, Heydon gave in to the Duke’s determination. “If your Grace insists. I find, then, that he will die very suddenly on the fifteenth day of January, two years hence—” He made a dramatic pause and then, leaning forward, hissed out his next words, while his blue eyes bored into the Duke’s. “And then, by popular demand of the people, your Grace will succeed to the throne of England for a long and glorious reign. The house of Villiers is destined to be the greatest royal house in the history of our nation!”

Buckingham stared at him, completely transfixed. “By Jesus! It’s incredible—and yet—What else do you find?” he demanded suddenly, eager to know everything.

It was as though he stood on the edge of some strange land from which it was possible to look forward into time and discover the shape of things to come. King Charles scorned such chicanery, saying that even if it were possible to see into the future it was inconvenient to know one’s fate, whether for good or ill. Well—there were other and cleverer men who knew how to turn a thing to their own ends.

“How will he—” Villiers checked himself, afraid of his own phraseology. “What will be the cause of so great a tragedy?”

Heydon glanced at his charts once more, as though for reassurance, and when he answered his voice was a mere whisper: “Unfortunately—the stars have it his Majesty will die by poison —secretly administered.”

“Poison!”

The Duke sat back, staring into the flames of the sea-coal fire, drumming his knuckles on the table-top, one eyebrow raised in contemplation. Charles Stuart to die of poison, secretly administered, and he, George Villiers, to succeed by popular demand to the throne of England. The more he thought about it the less incredible it seemed.

He was startled out of his reverie by a sudden sharp impatient rapping at the door. “What’s that! Were you expecting someone?”

“I had forgotten, your Grace,” whispered Heydon. “My Lady Castlemaine had an appointment with me at this hour.”

“Barbara! Has she been here before?”

“Only twice, your Grace. The last time three years since.” The rapping was repeated, loud and insistent, and a little angry too.

Buckingham got up quickly and went toward the door of the next room. “I’ll wait in here until she’s gone. Get rid of her as soon as possible—and as you value your nose don’t let her know I’m here.”

Heydon nodded his head and whisked the many papers and charts which concerned Charles II’s melancholy future off the table and into a drawer. As the Duke disappeared he went to answer the door. Barbara entered the room on a gust of wind; her face was entirely covered by a black-velvet vizard and there was a silver-blonde wig over her red hair.

“God’s eyeballs! What kept you so long? Have you got a wench in here?”

She tossed her black-beaver muff onto a chair, untied the hood she wore and flung off both it and the cloak. Then going to the fire to warm herself she nudged aside with her foot the thin mongrel dog that slept uneasily there, and which now looked up at her with injured resentment.

“God in Heaven!” she exclaimed, rubbing her hands together and shivering. “But I swear it’s the coldest night known to man! It’s blowing a mackerel-gale!”

“May I offer your Ladyship a glass of ale?”

“By all means!”

Heydon went to a dresser and poured out a glassful, saying with a sideways glance at her: “I regret that I cannot offer your Ladyship something more delicate—claret or champagne—but it is my misfortune that too many of my patrons are remiss in their debts.” He shrugged. “They say that comes of serving the rich.”

“Still plucking at the same string, eh?” She took the glass from him and began to swallow thirstily, feeling the sour ale slide down and begin to warm her entrails. “I have a matter of the utmost importance I want you to settle for me. It’s imperative that you make no mistake!”

“Was not my last prognostication correct, your Ladyship?”

He was leaning forward slightly from the waist, his big-jointed hands clasped before him, obsequiousness as well as an unctuous demand for praise in his voice and manner.

Barbara gave him an impatient glance over the rim of her glass. The Queen had been her enemy then. Now she was, without knowing it, as fast an ally as she had. Barbara Palmer, least of all, wanted to see another and possibly handsome and determined woman married to Charles Stuart; if anything should ever happen to Catherine her own days at Whitehall were done and she knew it.

“Don’t trouble yourself to remember so much!” she told him sharply. “In your business it’s a bad habit. I understand you’ve been giving some useful advice to my cousin.”

“Your cousin, madame?” Heydon was blandly innocent.

“Don’t be stupid! You know who I mean! Buckingham, of course!”

Heydon spread his hands in protest. “Oh, but madame—I assure you that you have been misinformed. His Grace was so kind as to release me from Newgate when I was carried there by reason of my debts—which I incurred because of the reluctance of my patrons to meet their charges. But he has done me no further honour since that time.”

“Nonsense!” Barbara drained the glass and set it onto the cluttered mantelpiece. “Buckingham never threw a dog a bone without expecting something for it. I just wanted you to know that I know he comes here, so you’ll not be tempted to tell him of my visit. I have as much evidence on him as he can get on me.”

Heydon, made more adamant by the knowledge that the gentleman under discussion was listening in the next room, refused to surrender. “I protest, madame—someone’s been jesting with your Ladyship. I swear I’ve not laid eyes on his Grace from that time to this.”

“You lie like a son of a whore! Well—I hope you’ll be as chary of my secrets as you are of his. But enough of that. Here’s what I came for: I have reason to think I’m with child again—and I want you to tell me where I may fix the blame. It’s most important that I know.”

Heydon widened his eyes and swallowed hard, his Adam’s apple bobbing convulsively in his skinny neck. Gadzooks! This was beyond anything! When a father had much ado to tell his own child, how could a completely disinterested person be expected to know it?

But Heydon’s wide reputation had not been built on refusal to answer questions. And now he took up the thick-lensed, green eye-glasses which he imagined gave him a more studious air, pinched them on the end of his nose, and both he and Barbara sat down. He began to pore intently over the charts on the table, meanwhile writing some mumbo-jumbo in a sort of bastard Latin and drawing a few moons and stars intersected by several straight lines.

From time to time he cleared his throat and said, “Hmmmm.”

Barbara watched him, leaning forward, and while he worked she nervously twisted a great diamond she wore on her left hand to cover her wedding-band—for she and Roger Palmer had long since agreed to have nothing more to do with each other.

At last Heydon cleared his throat a final time and looked across at her, seeing her white face through the blur of smoke from the tallow candles. “Madame—I must ask your entire confidence in this matter, or I can proceed no farther.”

“Very well. What d’you want to know?”

“I pray your Ladyship not to take offense—but I must have the names of those gentlemen who may be considered as having had a possible share in your misfortune.”

Barbara frowned a little. “You’ll be discreet?”

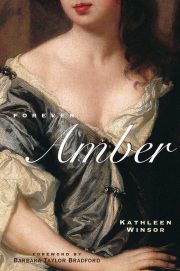

"Forever Amber" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Forever Amber". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Forever Amber" друзьям в соцсетях.