He raised his eyebrows faintly as he saw her standing there. “Madame Gwynne?”

Nelly gave a little curtsy. “Aye.”

“You know, I suppose, madame, that it is not I who sent for you?”

“Lord, I hope not, sir!” said Nelly. And then she added quickly, for fear of having hurt his feelings, “Not that I wouldn’t be pleased if it had been—”

“I understand, madame. And do you feel that you are correctly costumed for an interview with his Majesty?”

Nelly glanced down at her blue woollen gown and found it spotted with food and wine, stained in the armpits from many weeks of wear; there was a rent low in the skirt through which her red linen petticoat showed. She was unconcerned about her dress, as she was about all her appearance, and took her prettiness very much for granted. Though she was paid the good wage of sixty pounds a year she spent it carelessly, entertaining friends who came to see her, buying brandy for her fat sodden mother and gifts for Rose, tossing coins to every beggar who approached her in the streets.

“It’s what I was wearing, sir, when Mrs. Knight called for me. I didn’t know—I can go back and change—I have a very fine gown for special occasions—blue satin, with a silver petticoat and—”

“There isn’t time now. But here—try some of this.”

He crossed the room, picked up a bottle and gave it to her. Nelly took out the stopper, rolling her eyes ecstatically as she smelled the heavy-sweet odour. Then she tipped the bottle against her bodice until the perfume made a wet round circle, dabbing more of it on her breasts and wrists and live curling hair.

“That’s enough!” warned Chiffinch, and took it away from her. He glanced at a clock in a standing walnut case. “It’s time. Come with me.”

He walked out of the room and for an instant Nelly hesitated, gulping hard once, her heart pounding until she felt scarcely able to breathe; then with sudden resolution she lifted her skirts and followed him. They went out into a dim hall-way. Chiffinch lighted a candle from one which was burning there, stuck it into a brass holder and, turning, gave it to her.

“Here, this will light you up the stairs. At the top there’s a door which will be unlocked. Open it and go into the ruelle, but don’t make a sound until his Majesty comes for you. He may be occupied in talking to one of the ministers or writing a letter.”

She stared solemnly at him, nodding her head, and glanced up uncertainly toward the invisible door. In her trembling hand the candle sent shaking shadows across the walls. She looked back to Chiffinch again, as if for moral support, but he merely stood and stared at her, thinking that the King would never send again for this unkempt creature. Slowly she began to mount the stairs, holding up her skirts with her free hand; but her knees felt so weak she was sure she would never be able to reach the top. She kept on and on, feeling as though she mounted some endless flight in a terrifying dream. Chiffinch stood and watched her until he saw the door open, her profile silhouetted as she paused to blow out the candle, and then with a shrug of his shoulders he went back to his supper guests.

But he was mistaken, for not many nights later she was there again, clean this time and dressed in her blue satin and silver-cloth gown. There was about her still, however, a certain joyous carelessness, as though her spirits were too exuberant, too buoyantly full to take time with trifles. And this time Chiffinch greeted her with a smile, caught in her spell.

Nelly could not get over the wonder of this thing that had happened to her; she felt almost as though she were the first mistress Charles had taken. “Oh, Mary!” she cried breathlessly that first night when she came back out to the coach. “He’s wonderful! Why—he treated me just like—just like I was a princess!” And suddenly she had burst into tears, laughing and crying at once. I’ve fallen in love with him! she thought. Nelly Gwynne—daughter of the London streets, common trollop and public performer—in love with the King of England! Oh, what a fool! And yet, who could help it?

Not long after that Charles asked her what yearly allowance she would want and though she laughed and told him that she was ready to serve the Crown for nothing, he insisted that she name a price. The next time she came she asked Chiffinch what she should say.

“You’re worth five hundred a year, sweetheart—just for that smile.”

But when she came downstairs again she seemed sad and subdued and Chiffinch asked her what had happened. Nell looked at him for a moment, her chin began to quiver and suddenly she was crying. “Oh! He laughed at me! He asked me and I said five hundred pound and—and he laughed!” Chiffinch put his arms about her and while she sobbed he stroked the back of her head, telling her that she must be a little patient—that one day soon she would have much more than five hundred pounds from him.

She did not care about the money, but she did care a great deal that he should not consider her to be worth five hundred pounds—when he had spent much more than that on a single ring for Moll Davis.

Nelly and Moll Davis were well acquainted, for all the actors knew one another and knew also everything that happened in that small bohemian world which hung on the fringes of the Court. And because she liked people and was not inclined to be jealous she liked Moll despite their rivalry in the theatre —and now in another sphere—until she heard that Moll had been making fun of her because Charles had refused her the price she had asked.

“Nelly’s a common slut,” said Moll. “She won’t amuse him long.”

Moll herself made great capital of the rumour that she was the illegitimate daughter of the Earl of Berkshire, though actually her father was a blacksmith and she had been a milkmaid before coming to London to try her fortune.

“A common slut, am I?” said Nelly, when she heard that. “Well, perhaps I am. I don’t pretend to be anything else. But we’ll see whether I know how to amuse his Majesty or not!”

And she set out to visit Moll with a large box of homemade candy tucked under her arm. She threaded her way up one narrow crooked little alley and down another, flipping coins to a dozen beggars, waving an arm in greeting at various women hanging out their windows, stopping to talk to a little girl selling a platter of evil-smelling fish—she gave her a guinea to buy shoes and a cloak, for the winter was setting in. The day was sunny but cold and she walked along swiftly, her hair covered with a hood, her long woollen cloak slapping about her.

Moll lived not far from Maypole Alley in a second-floor lodging much like Nell’s own, though she had been bragging that his Majesty was going to take a fine house and furnish it for her. Nelly rapped at the door, greeted Moll with a broad grin, and stepped inside while the girl still stood staring at her. Her eye went quickly round the room, picking out evidences of new luxury: yellow-velvet drapes at the windows, a fine carved chair or two, the silver-backed mirror Moll was holding in her hand.

“Well, Moll!” Nelly tossed back her hood, unfastened the button at her throat. “Aren’t you going to make me welcome? Oh! Maybe you’ve got company!” She pretended surprise, as though she had just noticed that Moll wore only her smock and starched ruffled petticoat, with her feet in mules and her hair down her back.

Moll stared at her suspiciously, searching for the motive of this visit, and her plump dainty-featured little face did not smile. She knew that Nell must have heard the things she had been saying about her. She lifted her chin and pursed her lips, full of airs and newly acquired hauteur. “No,” she said. “I’m all alone. If you must know—I’m dressing to see his Majesty—at ten o’clock.”

“Heavens!” cried Nell, glancing at the clock. “Then you must hurry! It’s nearly six!” Nelly was amused. Imagine taking four hours to dress—even for the King! “Well, come on, then. We can gossip while you’re making ready. Here, Moll—I brought you something. Oh, it’s really nothing very much. Some sweets Rose and I made—with nuts in, the kind you always like.”

Moll, disarmed by this thoughtful gesture, reached for the box as Nell held it toward her, and finally she smiled. “Oh, thank you, Nell! How kind of you to remember how much I love sweets!” She opened it and took up a large piece, popped it into her mouth and began to munch, licked her fingers and extended the box to Nell.

Nelly declined. “No, thanks, Moll. Not just now. I ate some while we were making it.”

“Oh, it’s delicious, Nell! Such an unusual flavour, too! Come on in, my dear—I have some things to show you. Lord, I vow and swear there can’t be a more generous man in Europe than his Majesty! He all but pelts me with fine gifts! Just look at this jewel case. Solid gold, and every jewel on it is real—I know because I had a jeweller appraise it. And these are real sapphires on this patch-box too. And look at this lace fan! Have you ever seen anything to compare? Just think, he had his sister send it from Paris, especially for me.” She thrust two more pieces of candy into her mouth and her eyes ran over the gown Nelly was wearing. It was made of red linsey-woolsey, a material warm and serviceable enough, but certainly neither beautiful nor luxurious. “But then of course you didn’t want to wear your diamond necklace coming through the streets.”

Nell felt like crying or slapping her face, but she merely smiled and said softly, “I haven’t any diamond necklace. He hasn’t given me anything.”

Moll lifted her brows in pretended surprise and sat down to finish painting her face. “Oh, well—don’t fret about it, my dear. Probably he will—if he should take a fancy to you.” She picked up another piece of candy and then began to dust Spanish paper onto her cheeks with a hare’s foot. Nelly sat with her hands clasped over one knee and watched her.

Moll struggled with her hair for at least an hour, asking Nelly to put in a bodkin here or take one out there. “Oh, gad!” she cried at last. “A lady simply can’t do her own head! I vow I must have a woman—I’ll speak to him about it tonight.”

When the royal coach arrived at shortly after nine Moll gave an excited shriek, crammed the last three pieces of candy into her mouth, snatched up mask and fan and muff and gloves and went out of the room in a swirl of satins and scent. Nelly followed her down to the coach, wished her luck and waved her goodbye. But when the coach rattled off she stood and watched it and laughed until tears came to her eyes and her sides began to ache.

Now, Mrs. Davis! We’ll see what airs you give yourself next time we meet!

The following day Nelly went to the Duke’s Theatre with young John Villiers—Buckingham’s distant relation, somewhere in the sprawling Villiers tribe—to see whether her rival dared show herself on the boards after what had happened the night before. And Villiers—because he hoped to have a favour from her after the play—paid out four shillings for each of them and they took their seats in one of the middle-boxes, directly over the stage where Moll could not miss seeing them if she was there.

As they sat down Nell became conscious that there were two men in the box directly adjoining theirs and that both of them had watched her as she came in. She glanced at them, a smile on her lips—and then she gave a little gasp of horrified surprise and one hand went to her throat. It was the King and his brother, both apparently incognito for they were in ordinary dress, and the King wore neither the Star nor the Garter. In fact, their suits were far more conservative than those of most of the gallants buzzing away down in Fop Corner, next the stage.

Charles smiled, nodding his head slightly in greeting, and York gave her an intent stare. Nelly managed to return the smile but she wanted desperately to get up and run and would, in fact, have done so but that she did not care to draw the attention of the entire theatre upon them. And furthermore Betterton, wrapped in the traditional long black cloak, had now come out onto the apron of the stage to speak the prologue.

She stayed, but even after the prologue was over and the curtains had been drawn for the first act she sat rigid and tense, not daring to move her head, scarcely seeing the stage at all. Finally Villiers shook her elbow and whispered in her ear.

“What’s the matter with you, Nell? You look as though you’re in a fit!”

“Shh! I think I am!”

Villiers looked annoyed, not knowing whether to take her seriously or not. “D’you want to go?”

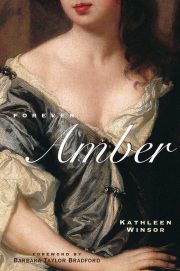

"Forever Amber" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Forever Amber". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Forever Amber" друзьям в соцсетях.