“Why—not for some time, I think.” Corinna hesitated a moment, as though uncertain whether she should say any more. Then quickly, with a kind of pride and the air of giving a precious confidence, she added: “You see, I’ve found that I’m with child and my husband thinks it would be unwise to start until after the baby has been born.”

Amber said nothing, but for a moment she felt sick with shock, her mind and muscles seemed paralyzed. “Oh,” she heard herself murmur at last. “Isn’t that fine.”

Angrily she told herself that she was being a fool. What did it matter if the woman was pregnant? What could that mean to her? She should be glad. For now he would be here longer than he had intended—much longer, for so far Corinna showed no evidence at all of pregnancy. She got to her feet then, saying that she must go, and Corinna pulled a bell-rope to summon a servant.

“Thank you so much for coming to call, your Grace,” she said as they walked toward the door. “I hope we shall become good friends.”

They paused just in the doorway now and Amber looked at her levelly. “I hope we shall too, madame.” Then, unexpectedly, she said something else. “I met your son yesterday in the Palace.”

A quick puzzled look crossed Corinna’s face, but instantly she laughed. “Oh, you mean young Bruce! But he isn’t my son, your Grace. He’s my husband’s son by his first wife—though truly, I love him as if he were my own.”

Amber said nothing but her eyes turned suddenly hard, and the swift fierce jealousy sprang up again. What do you mean! she thought furiously. You love him as if he were your own! What right have you to love him at all! What right have you to even know him! He’s mine—

Corinna was still talking. “Of course I never met the first Lady Carlton—I don’t even know who she was—but I think she must have been a very wonderful woman to have had such a son.”

Amber forced herself to give a little laugh, but there was no humour in it. “You’re mighty generous, madame. I should think you’d hate her—that first wife he had.”

Corinna smiled slowly. “Hate her? Why should I? After all—he belongs to me now.” She was speaking, of course, of the father, not the son. “And she left me her child.”

Amber turned about swiftly to shield her face. “I must go now, madame—Good-day—” She walked along the gallery but had gone only a few steps down the broad staircase when she heard Corinna’s voice again.

“Your Grace—you dropped your fan—”

She went on, pretending not to hear, unable to bear the thought of facing her again. But Corinna came hurrying after her, her high golden heels making a sharp sound as she walked along. “Your Grace,” she repeated, “you dropped your fan.”

Amber turned to take it. Corinna was standing just above her on the steps and now she smiled again, a friendly almost wistful smile. “Please don’t think me foolish, your Grace—but for a long while I’ve felt that you misliked me—”

“Of course I don’t—”

“No, I’m sure you don’t. And I shall think of it no more. Good-day, your Grace—and pray do come visit me again.”

CHAPTER SIXTY–THREE

ONE WARM NIGHT in early November there was a water-pageant on the Thames. This was a favourite entertainment of the King’s, and a group had gathered in his apartments to watch from the balconies. The skiffs and barges were decorated with flower-garlands and banners and a multitude of lanterns and flaring torches. From the other shore rockets shot up and fell back, hissing, into the water; streaks of yellow light crossed the sky. Music drifted from the boats and the King’s fiddlers played in a far corner of the room.

Under cover of the music, the rockets and confused chatter of voices, Lady Southesk spoke to Amber. “Who d’you think is Castlemaine’s newest conquest?”

Amber was not very much interested for she was concerned in keeping an eye on Bruce and Corinna where they stood, a few feet away. She shrugged carelessly. “How should I know? Who is it—Claude du Vall?” Du Vall was a highwayman of great current notoriety and he bragged that more than one lady of title had invited him to her bed.

“No. Guess again. A good friend of yours.”

Knowing Southesk, Amber now gave her a sharp glance.

“Who!”

Southesk looked over toward Lord Carlton and she lifted her brows significantly, smiling as she watched Amber’s face. Amber glanced swiftly at Bruce, then back at Southesk. She had turned white.

“That’s a lie!”

Southesk shrugged and gave a languid wave of her fan. “Believe me or not, it’s true. He was there last night—I have it on the very best—Lord, your Grace!” she cried now, in mock alarm. “Have a care—you’ll break your laces!”

“You prattling bitch!” muttered Amber, furious. “You breed scandal like a cess-pool breeds flies!”

Southesk gave her a look of hurt indignant innocence, tossed her curls and sailed off. Only a few moments later she was murmuring in someone else’s ear, a secret smile on her mouth as she nodded, very discreetly, in Amber’s direction. Amber, with as much nonchalance as she could muster, strolled over to link her arm through Almsbury’s, and as he greeted her she tried to give him a gay smile. But her eyes betrayed her.

“What’s the matter?” he whispered.

“It’s Bruce! I’ve got to see him! Right now!”

“After all, sweetheart—”

“Do you know what he’s been doing! He’s been laying with Barbara Palmer! Oh, I could murder him for that—”

“Shh!” cautioned the Earl, shifting his eyes about, for they were surrounded by a dozen pairs of alert ears. “What’s the difference? He’s done it before.”

“But Southesk is telling everyone! They’ll all be laughing at me! Oh, damn him!”

“Did it ever occur to you that they may also be laughing at his wife?”

“What do I care about her! I hope they are! Anyway, she doesn’t know it—and I do!”

When next she saw Bruce she tried to force him to promise her that he would never visit Barbara again, and though he refused to make any promises she later convinced herself that he did not. For she heard no more gossip and was sure that Barbara would not have been secretive about it. Her own affair with him, however, gained notoriety in an ever-spreading circle and though it seemed incredible, Corinna was evidently the only person left in fashionable London who did not know about them. But Corinna, Amber thought, was such a fool she would not have guessed that Bruce was her lover if she had found them in bed together.

She was mistaken.

The first night that Corinna had seen Amber she had been shocked by her costume and, later, sorry for her own bad manners in noticing it. The Duchess’s cold hostility she assumed to have been caused by that episode, and she had been genuinely pleased when she finally paid her a visit, thinking that at last she had forgotten it. But even before then Corinna had been aware that she was flirting with her husband.

In the four years since she had married him Corinna had watched a great many different kinds of women, from the black wenches on the plantation to the titled ladies of Port Royal, flirt with Bruce. Perfectly secure in his love for her, she had never been worried or jealous but, rather, amused and even a little pleased. She soon realized, however, that the Duchess of Ravenspur was potential trouble. She was, of course, extraordinarily lovely with her provocative eyes, rich honey hair and voluptuous figure—and what was more she had an attraction for men as powerful and combustible as was Bruce’s for women. She was no one any woman would like to find interested in the man she loved.

For the first time since her marriage Corinna was frightened.

Before long the other women began to drop hints. There were sly malicious little suggestions passed in the supper-table talk or when they came to call in the afternoons. A nudge and a glance would indicate the way her Grace leant over Lord Carlton as he sat at the gaming-table, her face almost touching his, one breast pressing his shoulder. Lady Southesk and Mrs. Middleton invited her to visit the Duchess with them one morning—and she met Bruce just coming out.

But Corinna refused to think what they so obviously wanted her to think. She told herself that surely she had enough sophistication to realize that idle people often liked to cause trouble among those they found happier and more content than themselves. And she wanted passionately to keep her belief in Bruce and in all that he meant to her. She was determined that her marriage should not be shaken because one woman was infatuated with her husband and others wished to destroy her faith in him. Corinna was not yet acquainted with Whitehall, for that took time, like accustoming oneself, after sunlight, to a darkened room.

But in spite of herself she found a mean resentful feeling of jealousy growing within her against the Duchess of Ravenspur. When she saw her look at Bruce or talk to him, sit across from him at the card-table, dance with him, or merely tap him on the shoulder with her fan as she went by, Corinna felt suddenly sick inside and cold with nervous apprehension.

At last she admitted it to herself; she hated that woman. And she was ashamed of herself for hating her.

And yet she did not know what she could do to stop the progress of what she feared was rapidly becoming an affair, in the London sense of the word. Bruce was no boy to be ordered around, forbidden to come home late or warned to stop ogling some pretty woman. Certainly there had been nothing so far in his behaviour which was real cause for suspicion. The morning she had met him leaving the Duchess’s apartments he had been perfectly cool and casual, not in the least embarrassed to be found there. He was as attentive and devoted to her as he had ever been, and she believed that she had a reasonably accurate idea as to where he spent his time when they were apart.

I must be wrong! she told herself. I’ve never lived in a palace or a great city before and I suppose I’m suspecting all sorts of things that aren’t true. But if only it were any other woman—I don’t think I’d feel the way I do.

To compensate in her heart for the suspicions she held against him, Corinna was more gay and charming than ever. She was so afraid that he would notice something different in her manner and guess at its cause. What would he think of her then—to know how mean she could be, how petty and jealous? And if she was wrong—as she persistently told herself she must be—it would be Bruce who would lose faith in her. Their marriage had seemed to her complete and perfect; she was terrified lest something happen through her own fault to spoil it.

Because of the Duchess she had come to dislike London—though it had been the dream of her life to revisit it someday—and she wished that they might leave immediately. She had begun to wonder if her Grace was the reason why he had suggested staying in London during her pregnancy—instead of going to Paris. That was why she did not dare suggest herself that they cross over to France to spend the time with his sister. Suppose he should guess her reason? For how could she explain such a wish when he had said it was for her own safety and both of them were so desperately anxious to have this child? (Their son had died the year before, not three months old, in the small-pox epidemic which was raging through Virginia.)

With some impatience and scorn she chided herself for her cowardice. I’m his wife—and he loves me. If this woman is anything to him at all she can be only an infatuation. It’s nothing that will last. I’ll still be living with him when he’s forgot he ever knew her.

One night, to her complete surprise, he inquired in a pleasant conversational tone: “Hasn’t his Majesty asked you for an assignation?” They had just come from the Palace and were alone now, undressing.

Corinna glanced at him, astonished. “Why—what made you say that?”

“What? It’s obvious he admires you, isn’t it?”

“He’s been very kind to me—but you’re his friend. Surely you wouldn’t expect a man to cuckold his friend?”

Bruce smiled. “My dear, a man is commonly cuckolded first by his friend. The reason’s simple enough—it’s the friend who has the best opportunity.”

Corinna stared at him. “Bruce,” she said softly. At the tone of her voice he turned, just as he was pulling his shirt off, and looked at her. “How strangely you talk sometimes. Do you know how that sounded—so cruel, and callous?”

He flung the shirt aside and went to her, taking her into his arms. Tenderly he smiled. “I’m sorry, my darling. But there are so many things about me you don’t know—so many years I lived before I knew you that I can never share with you. I was grown up and had watched my father die and seen my country ruined and fought in the army before you were ever born. When you were six months old I was sailing with Rupert’s privateers. Oh, I know—you think all that doesn’t make any difference to us now. But it does. You were brought up in a different world from mine. We’re not what we look like from the outside.”

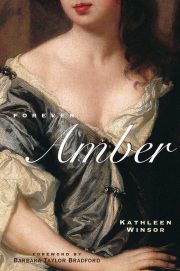

"Forever Amber" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Forever Amber". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Forever Amber" друзьям в соцсетях.