For several days Corinna, not knowing what she should do, did nothing. She thought it could do no good to accuse him. For what did it matter whether he would deny it or not—since the fact could not be denied? He was thirty-eight years old and had always done as he liked; he would not change now and she did not in any real sense want to change him for she loved him as he was. She felt lost and utterly helpless here in this strange land, surrounded by strange manners and strange customs. The ladies here, she realized, had all of them doubtless met this same situation many times, tossed it off with a smile and a witty phrase and turned to find their own amusement elsewhere. She had never realized so acutely as now what Bruce had often told her—that she was not a part of this world at all. Everything inside her recoiled from it with horror and disgust.

When he took her into his arms, kissed her, lay with her in bed, she could not put the thought of that other woman out of her mind. She would wonder, though she despised herself for it, how recently he had kissed the Duchess, and spoken the same words of passion he spoke to her. Why doesn’t he tell me? she asked herself desperately. Why should he cheat me and lie to me this way? It isn’t fair! But it was the Duchess she hated—not Bruce.

And then one day Lady Castlemaine paid her a visit.

King Charles had recently given the Duchess of Ravenspur a money grant of twenty thousand pounds and Barbara was so furious that she was determined to make trouble for her in some way. She was convinced that any woman—even a wife—of Corinna’s beauty must have considerable influence with a man and she hoped to spoil her Grace’s game with Lord Carlton. Very convenient to her purpose, Rochester had just written another of his scurrilous rhymed lampoons—this one on the intrigue between the Duchess and his Lordship.

It was Rochester’s habit to dress one of his footmen as a sentry and post him about the Palace at night, there to observe who went abroad at late hours. With information thus secured he would retire to his country-estate and write his nasty satires, several copies of which would be scribbled out and sent back anonymously to be circulated through the Court. They always pleased everyone but the subject, but the Earl was impartial—sooner or later every man and woman of any consequence might expect to feel the poisonous stab of his pen.

For the first few minutes of her visit Barbara made trifling but pleasant conversation—the brand-new French gowns called sacques, yesterday’s play at the Duke’s Theatre, the great ball which was to be held in the Banqueting House next week. And then all at once she was launched upon the current crop of love-affairs, who slept with whom, what lady feared herself to be with child by a man not her husband, who had most recently caught a clap. Corinna, guessing what all this was leading to, felt her heart begin to pound and her breath choked short.

“Oh, Lord,” continued Barbara airily, “the way things go here—I vow and swear an outsider would never guess. There’s more than meets the eye, let me tell you.” She paused, watching Corinna closely now, and then she said, “My dear, you’re very young and innocent, aren’t you?”

“Why,” said Corinna, surprised, “I suppose I am:”

“I’m afraid that you don’t altogether understand the way of the world—and as one who knows it only too well I’ve come to you as a friend to—”

Corinna, tired of the weeks of worry and uncertainty, the sense of sordidness and of helpless disillusion, felt suddenly relieved. Now at last it would come out. She need not, could not, pretend any longer.

“I believe, madame,” she said quietly, “that I understand some things much better than you may think.”

Barbara gave her a look of surprise at that, but nevertheless she drew from her muff a folded paper and extended it to Corinna. “That’s circulating the Court—I didn’t want you to be the last to see it.”

Slowly Corinna’s hand reached out and took it. The heavy sheet crackled as she unfolded it. Reluctantly she dragged her eyes from Barbara’s coolly speculative face and forced them down to the paper where eight lines of verse were written in a cramped angular hand. Somehow the weeks of misery and suspicion she had endured had cushioned her mind against further shock, for though she read the coarse brutal little poem it meant no more to her than so many separate words.

Then, as graciously as if Barbara had brought her a little gift, perhaps a box of sweetmeats or a pair of gloves, she said, “Thank you, madame. I appreciate your concern for me.”

Barbara seemed surprised at this mild reaction, and disappointed too, but she got to her feet and Corinna walked to the door with her. In the anteroom she stopped. For a moment the two women were silent, facing each other, and then Barbara said: “I remember when I was your age—twenty, aren’t you?—I thought that all the world lay before me and that I could have whatever I wanted of it.” She smiled, a strangely reflective cynical smile. “Well—I have.” Then, almost abruptly, she added, “Take my advice and get your husband away from here before it’s too late,” and turning swiftly she walked on, down the corridor, and disappeared.

Corinna watched her go, frowning a little. Poor lady, she thought. How unhappy she is. Softly she closed the door.

Bruce did not return home that night until after one o’clock. She had sent word to him at Whitehall that she was not well enough to come to Court, but had asked him not to change his own plans. She had hoped, passionately, that he would—but he did not. She found it impossible to sleep and when she heard him come in she was sitting up in bed, propped against pillows and pretending to read a recent play of John Dryden’s.

He did not come into the bedroom but, as always, went into the nursery first to see the children for a moment. Corinna sat listening to the sound of his steps moving lightly over the floor, the soft closing of the door behind him—and knew all at once that little Bruce was the Duchess’s son. She wondered why she had not realized it long ago. That was why he had told her almost nothing at all of the woman who supposedly had been the first Lady Carlton. That was why the little boy had been so eager to return and had coaxed his father to take him back to England. That was why they seemed to know each other so well—why she had sensed a closeness between them which could have sprung from no casual brief love-affair.

She was sitting there, almost numb with shock, when he came into the room. He raised his brows as if in surprise at finding her awake, but smiled and crossed over to kiss her. As he bent Corinna picked up Rochester’s lampoon and handed it to him. He paused, and his eyes narrowed quickly. Then he took it from her, straightened without kissing her and glanced over it so swiftly it was obvious he had already seen it, and tossed it onto the table beside the bed.

For a long moment they were silent, looking at each other. At last he said, “I’m sorry you found out this way, Corinna. I should have told you long ago.”

He was not flippant or gay about it as she had thought he might be, but serious and troubled. But he showed no shame or embarrassment, not even any regret, except for the pain he had caused her. For several moments she sat watching him, the opened book still in her lap, one side of her face lighted by the candles on a nearby table.

“She’s Bruce’s mother, isn’t she?” she said at last.

“Yes. I should never have made up that clumsy lie—but I wanted you to love him and I was afraid that if you knew the truth you wouldn’t. And now—how will you feel about him now?”

Corinna smiled faintly. “I’ll love him just as much as I ever did. I’ll love you both as much as I ever did.” Her voice was soft, gentle, feminine as a painted fan or the fragrance of lilacs.

He sat down on the bed facing her. “How long have you known about this?”

“I’m not sure. It seems like forever, now. At first I tried to pretend that it was only a flirtation and that I was being foolishly jealous. But the other women dropped hints and I watched you together and once I saw you at the New Exchange—Oh, what’s the use going over it again? I’ve known about it for weeks.”

For a time he was silent, sitting staring with a scowl down at his feet, shoulders hunched over, elbows resting on his spread legs. “I hope you’ll believe me, Corinna—I didn’t bring you to London for anything like this. I swear I didn’t expect it to happen.”

“You didn’t think she’d be here?”

“I knew she would. But 1 hadn’t seen her for two years. I’d forgotten—well, I’d forgotten a lot of things.”

“Then you saw her when you were here last—after we were married?”

“Yes. She was staying here at Almsbury House.”

“How long have you known her?”

“Almost ten years.”

“Almost ten years. Why, I’m practically a stranger to you.” He smiled, looking at her briefly, and then turned away again. “Do you love her, Bruce—” she asked him at last. “Very much?” She held her breath as she waited for him to answer.

“Love her?” He frowned, as though puzzled himself. “If you mean do I wish I’d married her, I don’t. But in another sense-Well, yes, I suppose I do. It’s something I can’t explain—something that’s been there between us since the first day I saw her. She’s—well, to be perfectly honest with you, she’s a woman any man would like to have for a mistress—but not for a wife.”

“But how do you feel now—now that you’ve seen her again and can’t give her up? Perhaps you’re sorry that you married me.”

Bruce looked at her swiftly, and then all at once his arms went about her, his mouth pressed against her forehead. “Oh, my God, Corinna! Is that what you’ve been thinking? Of course I’m not sorry! You’re the only woman I ever wanted to marry—believe me, darling. I never wanted to hurt you. I love you, Corinna—I love you more than anything on earth.”

Corinna nudged her head against him, and once more she felt happy and secure. All the doubts and fears of the past weeks were gone. He loves me, he doesn’t want to leave me. I’m not going to lose him after all. Nothing else mattered. Her life was so completely and wholly absorbed in him that she would have taken whatever he was willing to give her, left over from one love-affair or ten. And at least she was his wife. That was something the Duchess of Ravenspur could never have—she could never even acknowledge the son she had borne him.

At last Corinna said softly, her head resting just beneath his chin: “You were right, Bruce, when you said that I belonged to a different world from this one. I don’t feel that I’m part of it at all—no Court lady, I suppose, would dare admit she cared if her husband was in love with someone else. But I care and I’m not ashamed of it.” She tipped back her head and looked up at him. “Oh, darling—I do care!”

His green eyes watched her tenderly and at last he gave a faint rueful smile, his mouth touching the crown of her head just where the glossy dark hair parted. “It won’t do any good for me to tell you I’m sorry I’ve hurt you. I am. But if you read any more lampoons or hear any more gossip—Believe me, Corinna, it’s a lie.”

CHAPTER SIXTY–FOUR

IN HYDE PARK there was a pretty half-timbered cottage set beside a tiny lake, where all the fashionable world liked to stop for a syllabub or, if the weather was cold, a mug of lambs’-wool or hot mulled wine. It was almost Christmas now and too late in the year to ride, but there were several crested gilt coaches waiting in the cold grey-and-scarlet sunset outside the Lodge. The drivers and footmen smoked their pipes, sometimes stamped their feet to keep warm as they stood about in groups, laughing and talking together—exchanging the newest back-stairs gossip on the lords and ladies who had gone inside.

A sea-coal fire was burning high in the oak-panelled great room. There was a cluster of periwigged and beribboned young fops about the long bar, drinking their ale or brandy, throwing dice and matching coins. Several ladies were seated at tables with their gallants. Waiters with balanced trays moved about among them and three or four fiddles were playing.

Amber—wearing an ermine-lined hooded cloak of scarlet velvet and holding a syllabub glass in one hand and her muff of dripping ermine tails in the other—stood near the fireplace talking to Colonel Hamilton, the Earl of Arran and George Etherege.

She chattered fluently and there was an ever-shifting, vivacious play of expression over her face. She seemed to be engrossed in the three of them. But all the while her eyes watched the door—it never opened that she did not know who came in or went out. And then, at last, the languid golden Mrs. Middleton sauntered in with Lord Almsbury at her elbow. Amber did not hesitate an instant. Excusing herself from the three men she wove her way across the room to where the newcomers were standing, Jane still pausing just within the doorway to give the crowd time to discover her.

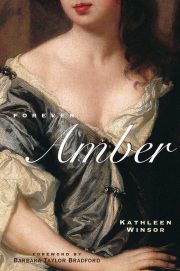

"Forever Amber" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Forever Amber". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Forever Amber" друзьям в соцсетях.