She stared at him in surprise. “A hundred pound, sir!”

She drew closer to the trundle then and looked at Amber, whose fingers were picking restlessly at the blanket Bruce had thrown over her, though but for the nervous movements of her hands she would have seemed to be totally unconscious. There were dirty green circles beneath her eyes and the lower part of her face was shiny with the bile and saliva which had dried there; she had not vomited at all for the past three hours.

The woman shook her head. “She’s mighty sick, your Lordship. I don’t know—”

“Of course you don’t know!” snapped Bruce with angry impatience. “But you can try! She’s still dressed. Take her clothes off, bathe her face and hands—get her into the sheets. She’ll be more comfortable at least. She’s been cooking for me and you’ll find soup and whatever else you need in the kitchen. There are clean towels and sheets in that room—The floor must be mopped, and the parlour cleaned. A woman died there yesterday. Now get to work! What’s your name?” he added, as an afterthought.

“Mrs. Sykes, sir. Yes, sir.”

Mrs. Sykes, who told Bruce that she had been a wet-nurse but had lost her job because her husband had died of the plague, worked hard throughout the day. Bruce gave her no opportunity to loaf or to rest, and despite the fact that she knew he was helpless and unable to get out of bed she obeyed his commands meekly—whether from respect of the nobility or one hundred pounds he did not know or care.

But by nightfall Amber seemed, if possible, to be even worse. A carbuncle had begun to swell in her right groin and though it grew larger it remained hard and gave no indication that it would suppurate. Sykes was anxious about that, for it was the worst possible sign, and not even the mustard plasters she applied—which blistered the skin—seemed to have any effect.

“What can we do?” Bruce asked her. “There must be something we can do! What have you done for your patients when the carbuncle wouldn’t break?”

Sykes was staring down at Amber. “Nothing, sir,” she said slowly. “Most usually they die.”

“She’s not going to die!” he cried. “We’ll do something. We’ve got to do something—She can’t die!” He looked less well than he had the day before but he forced himself to stay awake, as though he could keep her alive by holding a vigil over her.

“We might cut into it,” she said. “If it’s still like this tomorrow. That’s what the doctors do. But the pain of the knife sometimes drives ’em mad—”

“Shut up! I don’t want to hear it! Go out and get her something to eat.”

He was almost exhausted and his temper was quick and savage, for he suffered agonizingly over his own impotence. It went through his mind over and over again. She’s sick because of me and now, when she needs me, I lie here like a sot and am able to do nothing!

Almost to his surprise, Amber lived through the night. But by morning her skin was beginning to take on a dusky colour, her breathing grew more shallow and her heart-beats fainter. Sykes told him that those things meant approaching death.

“Then we’ll cut the boil open!”

“But it might kill her!”

Sykes was afraid to do anything, for it seemed that no matter what she did the patient would die and she would lose the greatest fortune she had ever imagined.

He almost shouted at her. “Do as I say!” Then his voice dropped again, he spoke to her quietly but with a swift commanding urgency. “Over in the top drawer of that table there’s a razor—get it. Take the cord off the drapes and bind her knees and ankles together. Wrap the cord around the trundle so she can’t move, and tie her wrists to the corners. Get some towels and a basin. Hurry!”

Sykes scrambled nervously about the room, but within a couple of minutes she had followed his directions. Amber lay bound securely to the trundle and still completely unconscious.

Bruce was close to the edge of the bed. “Pray God she doesn’t know—” he muttered and then: “Now! Take the razor and cut into it—quick and hard! It’ll hurt less that way. Quick!” His right fist clenched and the veins in it swelled.

Sykes looked at him in horror, the razor held tight in her hand. “I can’t, your Lordship. I can’t.” Her teeth began to chatter. “I’m scared! What if she dies under it!”

Bruce was pouring sweat. He licked his tongue over his dry lips and gave a convulsive swallow. “You can, you fool! You’ve got to! Now—do it now!”

Sykes continued to stare at him for a moment and then, as though hypnotized into obedience by the sheer force of his will, she bent and placed the edge of the razor against the hard red knob high up on Amber’s groin. At that moment Amber stirred and her head turned toward Bruce. Sykes gave a start.

“Cut it open!” said Bruce hoarsely, his clenched fist trembling with helpless rage. His face was dark with the rush of blood and the cords in his neck and temples were thick as ropes and throbbing.

With sudden resolution Sykes jammed the razor into the lump, but as she did so Amber moaned and the moan slid in crescendo to a quivering scream. Sykes let go of the razor and stepped back to stand staring at Amber who was struggling now to free herself, twisting frantically in an effort to escape the pain, shrieking again and again.

Bruce began to get out of bed. “Help me!”

Sykes came swiftly, put one arm around his back, the other beneath his elbow, and in an instant he had dropped on his knees beside the trundle and seized the razor.

“Hold her! Here! By the knees!”

Again Sykes did as she was told, though Amber continued to writhe, shrieking, her eyes rolling like a frenzied animal’s. With all the strength he had left Bruce forced the razor into the hard mass and twisted it to one side. As he pulled it out again the blood spurted, splattering onto his body, and Amber dropped back, unconscious. His head fell helplessly onto his fist; his own wound had opened once more and the bandage showed fresh and red.

Sykes was trying to help him get up. “Your Lordship! Ye must get back into bed! Your Lordship—please!”

She wrenched the razor from his hand and with her help he managed to crawl back onto the bed. She flung a blanket over him and turned immediately to Amber whose skin was now white and waxen. Her heart was beating, very faintly. Quantities of blood poured from the opening, but there was no pus and the poison was not draining.

Sykes worked furiously, at her own initiative now, for Bruce had lapsed into coma. She kept the blood sponged away; she heated bricks and every hot water bottle in the house and packed them about Amber; she laid hot cloths on her forehead. If there was any way she could be saved, Sykes intended to get her hundred pounds.

It was almost an hour before Bruce returned to consciousness and then, with a sudden start, he tried to sit up. “Where is she! You didn’t let them take her!”

“Hush, sir! I think she’s sleeping. She’s still alive and I think, sir, that she’s better.”

He leaned over to look at her. “Oh, thank God, thank God. I swear it, Sykes, if she lives you’ll get your hundred pound. I’ll make it two hundred for you.”

“Oh, thank you, sir! But now, sir—you’d better lie back there and rest yourself—or you might not fare so well, sir.”

“Yes, I will. Wake me if she gets any—” The words trailed off.

At last the pus began to seep up and the wound started to drain off its poison. Amber lay perfectly still again, drowned in coma, but the dark tinge was gone from her skin and though her cheeks had sunk against the bones and there were crape-like circles around her eyes, her pulse had a stronger, surer beat. The sound of tolling bells seemed suddenly to fill the room. Sykes gave a start, then relaxed; they would not toll tonight for her patient.

“I’ve worked hard for my money, sir,” Sykes said to him on the morning of the fourth day. “And I’m sure she’ll live now. Can I have it?”

Bruce smiled. “You have worked hard, Sykes. And I’m more grateful than I can tell you. But you’ll have to wait a while longer.” He would not give her any of the jewellery, partly because it was Amber’s personal property, partly because it might have encouraged her to outright thievery or some other mischief. Sykes had served her purpose, but he knew that it would be foolish to trust her. “There are only a few shillings in the house—and they’ve got to be spent for food. As soon as I can go out I’ll get it for you.”

He was able to sit up now, most of the day, and when it was necessary he could get out of bed, but never stayed more than a few minutes at a time. His persistent weakness seemed both to amuse and infuriate him. “I’ve been shot in the stomach and run through the shoulder,” he said one day to Sykes as he walked slowly back to the bed. “I’ve been bitten by a poisonous snake and I’ve had a tropical fever—but I’ll be damned if I’ve ever felt like this before.”

Most of the time he spent reading, though there were only a few books in the apartment and he had already seen most of them. Some had been there as part of the furnishings and they were a respectable assortment, including the Bible, Hobbes’s “Leviathan,” Bacon’s “Novum Organum,” some of the plays of Beaumont and Fletcher, Browne’s “Religio Medici.”

Amber’s collection, though small, was more lively. There was an almanac, thumbed and much scribbled in, the lucky and unlucky days starred, as well as those for purging or bloodletting, though so far as he knew she seldom did either. Her familiar scrawl was marked across the fly-leaf of half-a-dozen others: “L’École des Filles,” “The Crafty Whore,” “The Wandering Whore,” “Annotations upon Aretino’s Postures,” “Ars Amatoria,” and—evidently because it was currently fashionable —Butler’s “Hudibras.” All but the last had obviously been well read. He smiled to see them, for though the same volumes would doubtless have been found in the closet of almost any Court lady they were nevertheless amusingly typical of her.

He always sat near the edge of the bed where he could watch her, and she made no movement or slightest sound which he did not notice. She was, very slowly, getting better, though the constant sloughing of the wound worried him, for it continued to open wider and deeper until it had spread over an area with a two-inch diameter. But both he and Sykes were convinced that if the incision had not been made she would have died.

Sometimes, to his horror, she would suddenly put up her hands as though to ward off a blow, and cry out in a piteous voice. “Don’t! No! Please! Don’t cut me!” And the cry would slide off in a shuddering moan that turned him cold and wet. After that she always lapsed again into unconsciousness, though sometimes even in coma she twitched and squirmed and made soft whimpering sounds.

It was the seventh day before she saw and recognized him. He had come in from the parlour and found her propped against Sykes’s arm swallowing some beef-broth, languidly and without interest. He had a blanket flung over his shoulders and now he knelt beside the trundle to watch her.

She seemed to sense him there and her head turned slowly. For a long moment she looked at him, and then at last she whispered softly: “Bruce?”

He took her hand in both of his. “Yes, darling. I’m here.”

She forced a little smile to her face and started to speak again, but the words would not come, and he moved away to save her the effort. But the next morning, early, while Sykes was combing out her hair she spoke to him again, though her voice was so thin and weak that he had to lean close to hear it.

“How long ’ve I been here?”

“This is the eighth day, Amber.”

“Aren’t you well yet?”

“Almost. In a few days I’ll be able to take care of you.”

She closed her eyes then and breathed a long tired sigh. Her head rolled over sideways on the pillow. Her hair, lank and oily with most of the curl gone, lay in thick skeins about her head. Her collar-bones showed sharply beneath the taut-stretched skin, and it was possible to see her ribs.

That same day Mrs. Sykes fell sick, and though she protested for several hours that it was nothing at all, merely a slight indisposition from something she had eaten, Bruce knew better. He did not want her taking care of Amber and suggested that she lie down in the nursery and rest, which she did immediately. Then, wrapping himself in a blanket, he went out to the kitchen.

Sykes had had neither the time nor the inclination and probably not even the knowledge for good housekeeping and all the rooms were littered and untidy. Puffs of dust moved about on the floors, the furniture was thickly coated, stubs of burnt-down candles lay wherever she had tossed them. In the kitchen there were stacks of dirty pans and plates, great pails full of soaking bloody rags or towels, and the food had not been put away but left out on the table or even set on the floor.

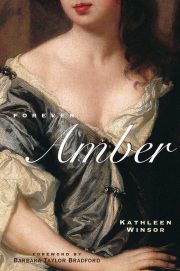

"Forever Amber" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Forever Amber". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Forever Amber" друзьям в соцсетях.