She tried to tell him something of how she felt and added, “I never used to feel that way about it when I lived there—yet God knows I don’t want to go back!”

He smiled at her tenderly. “You’re growing older, darling.”

Amber. looked at him with surprise and resentment. “Old! Marry come up! I’m not so old! I’m not twenty-two yet!” Women began to feel self-conscious about age as soon as they reached twenty.

He laughed. “I didn’t mean that you’re growing old. Only that you’re enough older you’ve begun to have memories—and memories are always a little sad.”

She digested that thoughtfully, and gave a light sigh. It was just at gloaming and they were walking back to the Sapphire through a low lush river meadow. Nearby they could hear the castanet-like voice of a frog, and the stag-beetles buzzing noisily.

“I suppose so,” she agreed. Suddenly she looked up at him. “Bruce—remember the day we met? I can shut my eyes and see you so plain—the way you sat on your horse, and the look you gave me. It made me shiver inside—I’d never been looked at like that before. I remember the suit you had on—it was black velvet with gold braid—Oh, the most wonderful suit! And how handsome you looked! But you scared me a little bit too. You still do, I think—I wonder why?”

“I’m sure I can’t imagine.” He seemed amused, for she often brought up such remnants of the past, and she never forgot a detail.

“Oh, but just think!” They were crossing a shaky little wooden bridge now, Amber walking ahead, and suddenly she turned and looked up at him. “What if Aunt Sarah hadn’t sent me that day to take the gingerbread to the blacksmith’s wife! We’d never even have known each other! I’d still be in Marygreen!”

“No you wouldn’t. There’d have been other Cavaliers going through—you’d have left Marygreen whether you’d ever seen me or not.”

“Why Bruce Carlton! I would not! I went with you because it was fate—it was in the stars! Our lives are planned in heaven, and you know it!”

“No, I don’t know it, and you don’t either. You may think it, but you don’t feel it.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about.” They were across the bridge, strolling along side by side again, and Ambers switched petulantly at the grass with a little twig she had picked up. Suddenly she flung it away and faced him squarely, her hands catching at his arms. “Don’t you think that we were meant for each other, Bruce? You must think so—now.”

“What do you mean, ‘now’?”

“Why—after everything we’ve been through together. Why else did you stay and take care of me then? You could have gone away when you were well and left me alone—if you hadn’t loved me.”

“My God, Amber, you take me for a greater villain than I am. But of course I love you. And in a sense I agree with you that we were meant for each other.”

“In a sense? What do you mean by that?”

His arms went about her, the fingers of one hand combing through the long glossy mass of her hair, and his mouth came down close to hers. “This is what I mean,” he said softly. “You’re a beautiful woman—and I’m a man. Of course we were meant for each other.”

But, though she did not say anything more about it just then, that was not what she wanted to hear. When she had stayed with him in London, at the risk of her own life, she had not thought of or expected either gratitude or return. But when he had stayed with her, had cared for her as tenderly and devotedly as she had for him—she believed then that he had changed, and that now he would marry her. She had waited, with growing apprehension and misgiving, for him to speak of it—but he had said nothing.

Oh, but that’s not possible! she told herself again and again. If he loved me enough to do all that—he loves me enough to marry me. He thinks I know he will as soon as we’re where we can—that’s why he hasn’t said anything—He thinks I—

But not all her brave assurances could still the doubts and torment that grew more insistent with each day that passed. She began to realize that, after all, nothing had changed—he still intended to go on with his life just as he had planned it, as though there had never been a plague.

She wanted desperately to talk to him about it but, afraid of blighting the harmony there was between them—almost perfect for the first time since they had known each other—she forced herself to put it off and wait for some favourable opportunity.

Meanwhile the days were going swiftly. The holly had turned scarlet; loaded wagons stood in the orchards, and the air was fragrant with the fresh autumn smell of ripe red apples. Once or twice it rained.

They left the boat at Abingdon and stayed overnight in a quiet old inn. The host and hostess finally accepted their certificates-of-health, but with obvious misgivings and only because Bruce gave them five extra guineas—though their money supply was now almost gone. But the next morning they hired horses and a guide and set out for Almsbury’s country home, some sixty miles away. They followed the main road to Gloucester, spent the night there and went on the next day. When they reached Barberry Hill in mid-morning Amber was thoroughly exhausted.

Almsbury came out of the house with a yell. He swung her up off her feet and kissed her and pounded Bruce on the back, telling them all the while how he had tried to find them both—never guessing that they were together—how scared he had been, and how glad he was to have them there with him, alive and well. Emily seemed just as pleased, though considerably less exuberant, and they went inside together.

Barberry Hill had not been the most important country possession of the Earls of Almsbury, but it was the one he had been able to have restored to the family. Though less imposing than Almsbury House in the Strand, it had a great deal more charm. It was L-shaped, built of red brick, and lay intimately at the foot of a hill. Part of it was four stories high, part only three; there was a pitched slate roof with many gables and dormer-windows and several spiralling chimneys. All the rooms were decorated with elaborate carvings and mouldings, the ceilings were crusted with plaster-work as ornamental as the frosting on a Twelfth Day cake, the grand staircase was a profusion of late Elizabethan carving and there were gay gorgeous colours everywhere.

Almsbury immediately sent a party of men to find Nan Britton and bring her there. And when Amber had rested and put on one of Lady Almsbury’s gowns—which she did not think had any style at all and which she had to pin in at the sides—she and Bruce went to the nursery. They had not seen their son for more than a year, not since the mornings when they had met at Almsbury House, and he had grown and changed considerably.

He was now four and a half years old, tall for his age, healthy and sturdy. His eyes were the same grey-green that Bruce’s were and his dark-brown hair hung in loose waves to his shoulders, rolling over into great rings. He had been put into adult clothes —a change which was made at the age of four—and they were in every way an exact replica of Lord Carlton’s, even to the miniature sword and feather-trimmed hat.

These grown-up clothes for children seemed symbolic of the hot-house forcing of their lives. For he was already learning to read and write and do simple arithmetic; riding-lessons had begun, as well as instruction in dancing and deportment. Before long there would be more lessons: French, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew; fencing, music, and singing. Childhood was brief, manhood came early, for life was an uncertain risk at best. There was no time to be lost.

When they entered the nursery little Bruce, with Almsbury’s eldest son, was seated at a tiny table studying his horn-book. But obviously he knew that his parents were coming to see him, for just as they opened the door he looked around with a quick expectancy which suggested many previous eager glances in that direction. As the horn-book went clattering to the floor, he was off the chair and running toward them joyously: But instantly, at a sharp word from his nurse, he stopped, swept off his hat and bowed with great ceremony, first to Bruce and then to Amber.

“I’m glad to see you, sir. And, madame.”

But Amber was not in awe of the nurse. She rushed forward, dropped to her knees and swooped him into her arms, covering his pink cheeks with passionate kisses. Tears glistened in her eyes and began to fall, but she was laughing with happiness. “Oh, my darling! My darling! I thought I would never see you again.”

His arms were about her neck. “But why, madame? I was sure I’d see you both again one day.”

Amber laughed and murmured quickly beneath her breath: “Damn the nurse! Don’t call me madame! I’m your mother and that’s what I’ll be called!” They laughed together at that, he whispered “Mother,” and then gave a quick half-apprehensive, half-defiant look over his shoulder to where the nurse stood watching them.

He was more reserved with Bruce and apparently felt that they were both gentlemen from whom such demonstrations were not expected. It was obvious, however, that he adored his father. Amber felt a pang of jealousy as she watched them but she scolded herself for her pettiness and was even a little ashamed. After an hour or so they left the nursery and started back down the long gallery toward their own adjoining apartments at the opposite end of the building.

All of a sudden Amber said: “It isn’t right, Bruce, for him to live this way. He’s a bastard. What’s the use for him to learn to carry himself like a lord—when God knows how he’ll shift once he’s grown-up.”

She looked up at him sideways, but his expression did not change and now, as they reached the door to her apartment, he opened it and they went in. She turned about quickly to face him, and knew at that instant he was about to say something which he expected would make her angry.

“I’ve been wanting to talk to you about this, Amber—I want to make him my heir—” And then, as a flash of hope went over her face, he hastily added: “In America no one would know whether he’s legitimate or not—they’d think he was the child of an earlier marriage.”

She stared at him incredulously, her face recoiling as though from a sudden cruel slap. “An earlier marriage?” she repeated softly. “Then you’re married now.”

“No, I’m not. But I’ll marry someday—”

“That means you still don’t intend to marry me.”

He paused, looking at her for a long moment, and one hand started to move in an involuntary gesture, but dropped to his side again. “No, Amber,” he said at last. “You know that. We’ve talked this all over before.”

“But it’s different now! You love me—you told me so yourself! And I know you do! You must! Oh, Bruce, you didn’t tell me that to—”

“No, Amber, I meant it. I do love you, but—”

“Then why won’t you marry me—if you love me?”

“Because, my dear, love has nothing to do with it.”

“Nothing to do with it! It has everything to do with it! We’re not children to be told by our parents who we’ll marry! We’re grown up and can do as we like—”

“I intend to.”

For several seconds she stared at him, while the desire to lash out her hand and slap him surged and grew inside her. But something she remembered—a hard and glittering expression in his eyes—held her motionless. He stood there watching her, almost as though waiting, and then at last he turned and walked out of the room.

Nan arrived a fortnight later with Susanna, the wet-nurse, Tansy and Big John Waterman. They had spent the four months going from one village to another, fleeing the plague. Despite everything only one cart-load had been stolen; almost all of Amber’s clothes and personal belongings were intact. She was so grateful that she promised Nan and Big John a hundred pounds each when they returned to London.

Bruce was enchanted with his seven-months-old daughter. Susanna’s eyes were no longer blue but now a clear green and her hair was bright pure golden blonde, not the tawny colour of her mother’s. She did not very much resemble either Bruce or Amber but she gave every promise of being a beauty and seemed already conscious of her destiny, for she flirted between her fingers and giggled delightedly at the mere sight of a man. Almsbury, teasing Amber, said that at least there could be no doubt as to her mother’s identity.

The very day of Nan’s arrival Amber put off Emily’s unbecoming black dress and, after considerable deliberation, selected one of her own: a low-bosomed formal gown of copper-coloured satin with stiff-boned bodice and sweeping train. She painted her face, stuck on three patches, and for the first time in many months Nan dressed her hair again in long ringlets and a high twisted coil. Among her jewellery she found a pair of emerald ear-rings and an emerald bracelet.

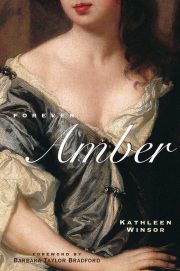

"Forever Amber" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Forever Amber". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Forever Amber" друзьям в соцсетях.