She thought of every possible solution, but was compelled to abandon each in turn. If she left him he would have all her money—and she would have no title. To get a divorce was almost impossible and would have required an act of Parliament; not even Castlemaine had obtained a divorce. Annulment was almost as difficult, for the case must rest upon impotence or sterility, and how was she to prove herself a virgin or him incompetent? To make matters worse, the courts, she knew, were not inclined to side with a woman. And so at last she decided that if it had been possible for her to tolerate him before they were married it should be possible now. She began to speak civilly to him once more, joined him at dinner, went into the library to search among the books when he was there. She took an extraordinary care of her appearance, in the hope of buying what she wanted by pandering to his salaciousness.

On the afternoon the precious Correggio arrived, she went down to watch it being unpacked. When at last it was hung, the workmen gone, and they stood before the fireplace looking up at it, Amber sneaked him a glance and found that he was smiling. As always, when he had just acquired another coveted and admired object, he seemed in a pleasanter, more tractable mood.

“I wonder, your Lordship,” she began tentatively, her eyes stealing toward him again, and then back to the picture, “I wonder if I might go abroad today—just for a drive. I haven’t been out of the house in three weeks and I swear it’s making me pale and sallow. Don’t you think so?” She looked at him anxiously.

He turned and faced her directly, a faint amused smile on his mouth. “I thought your pleasant humour of the past few days meant a request would soon be forthcoming. Very well, you may go.”

“Oh! thank you, sir! Can I go now?”

“Whenever you like. My coachman will drive you—and, by the way, he’s served me for thirty years and is not to be bribed.”

Her smile suddenly froze, but she concealed her anger swiftly for fear of having the privilege revoked. Then swooping up her skirts she ran out of the room, down the hall, and up the stairs two at a time. She burst into their apartments with a cry of triumph that made Nan start and almost drop her needlework.

“Nan! Get your cloak! We’re going abroad!”

“Going abroad! Oh, Lord, are we? Where?” Nan had been sharing her mistress’s confinement—save for a few brief excursions to buy ribbons or gloves or a fan—and was as tired of it as Amber.

“I don’t know! Somewhere—anywhere—Hurry!”

The two women left the house in a swirl of velvet skirts and fur muffs, getting into the coach with as much laughter and excitement as if they had just arrived from Yorkshire to see the London sights. The air was so sharp and fresh it stung the nostrils. The day was grey and windy, and petals blown from peach trees drifted through the air, falling like flakes of snow onto the roof-tops and into the mud.

There was still plague in the town, though there were usually not more than half-a-dozen deaths a week, and it had retired once more to the congested dismal districts of the poor. By now it was almost impossible to find a shut-up house. The streets were as crowded as ever, the vendors and ’prentices as noisy, and the only sure sign that plague had recently passed that way were the many plaintive notices stuck up in windows: “Here is a doctor to be let.” For the doctors, by their wholesale desertion, had forfeited even what reluctant and suspicious trust they had once been able to command. A fifth of the town’s population was dead, yet nothing seemed to have changed—it was the same gay bawdy stinking brilliant dirty city of London.

Amber, delighted to be out again, looked at and exclaimed upon everything:

The little boy solemnly plying his trade of snipping silver buttons from the backs of gentlemen’s coats as they strolled unsuspectingly down the street. The brawl between some porters and apprentices who, setting up the traditional cry of “ ’Prentices!” Prentices!” brought their fellows flying to the rescue with clubs and sticks. A man performing on a tight-rope for a gape-mouthed crowd at the entrance to Popinjay Alley. The women vendors sitting on street corners amid their great baskets of sweet-potatoes, spring mushrooms, small sour oranges, onions and dried pease and new green dandelion tops.

She had directed the coachman to drive to Charing Cross by way of Fleet Street and the Strand, for there were a number of fashionable ordinaries in that neighbourhood. And after all, if she should chance in passing to see someone she knew and stopped to speak a word with him out of mere civility—why, no one could reasonably object to anything so innocent as that. Amber kept her eyes wide open and advised Nan to do likewise, and just as they were approaching Temple Bar she caught sight of three familiar figures gathered in the doorway of The Devil Tavern. They were Buckhurst, Sedley and Rochester, all three evidently half-drunk for they were talking and gesticulating noisily, attracting the attention of everyone who passed by.

Instantly Amber leaned forward to rap on the wall, signalling the driver to stop, and letting down the window she stuck out her head. “Gentlemen!” she cried. “You must stop that noise or I’ll call a constable and have you all clapped up!” and she burst into a peal of laughter.

They turned to stare at her in astonishment, momentarily surprised into silence, and then with a whoop they advanced upon the coach. “Her Ladyship, by God!” “Where’ve you been these three weeks past!” “Why’n hell haven’t we seen you at Court?” They hung on one another’s shoulders and leaned their elbows on the window-sill, all of them breathing brandy and smelling very high of orange-flower water.

“Why, to tell you truth, gentlemen,” said Amber with a sly smile and a wink at Rochester, “I’ve had a most furious attack of the vapours.”

They roared with laughter. “So that formal old fop, your husband, locked you in!”

“I say an old man has no business marrying a young woman unless he can entertain her in the manner to which she’s accustomed herself. Can your husband do that, madame?” asked Rochester.

Amber changed the subject, afraid that some of the footmen or the loyal old driver might have been told to listen to whatever she said and report it. “What were you all arguing about? It looked like a conventicle-meeting when I drove up.”

“We were considering whether to stay here till we’re drunk and then go to a bawdy-house—or to go to a bawdy-house first and get drunk afterward,” Sedley told her. “What’s your opinion, madame?”

“I’d say that depends on how you expect to entertain yourselves once you get there.”

“Oh, in the usual way, madame,” Rochester assured her. “In the usual way. We’re none of us yet come to those tiresome expedients of old-age and debauchery.” Rochester was nineteen and Buckhurst, the eldest, was twenty-eight.

“Egad, Wilmot,” objected Buckhurst, who was now drunk enough to talk without stammering. “Where’s your breeding? Don’t you know a woman hates nothing so much as to hear other women mentioned in her presence?”

Rochester shrugged his thin shoulders. “A whore’s not a woman. She’s a convenience.”

“Come in and drink a glass with us,” invited Sedley. We’ve got a brace of fiddlers in there and we can send to Lady Bennet for some wenches. A tavern will serve my turn as well as a brothel any day.”

Amber hesitated, longing to go and wondering if it might be possible to bribe the coachman after all. But Nan was nudging her with her elbow and grimacing and she decided that it was not worth the risk of being locked up for another three weeks, or possibly longer. And worst of all, she knew, Radclyffe might be angry enough even to send her into the country—the favourite punishment for erring wives, and the most dreaded. By now her coach had begun to snarl the traffic. There were other coaches waiting behind, and numerous porters and carmen, vendors, beggars, apprentices and sedan-chair-men—all of them beginning to growl and swear at her driver, urging him to move on.

“There’s some of us got work to do,” bawled a chair-man, “even if you fine fellows ain’t!”

“I can’t go in,” said Amber. “I promised his Lordship I wouldn’t get out of the coach.”

“Make way there!” bellowed another man trundling a loaded wheelbarrow.

“Make room there!” snarled a porter.

Rochester, not at all disturbed, turned coolly and made them a contemptuous sign with his right hand. There was a low, sullen roar of protest at that and several shouted curses. Buckhurst flung open the coach-door.

“Well, then! You can’t get out—but what’s there to keep us from getting in?”

He climbed in—followed by Rochester and Sedley—and settled himself between the two women, sliding an arm about each. Sedley stuck his head out the window. “Drive on! St. James’s Park!” As they rolled off, Rochester gave an impertinent wave of his hand to the crowd. There was a breeze blowing up and it now began to rain, suddenly and very hard.

Amber came home in a gale of good humour and high spirits. Tossing off her rain-spattered cloak and muff in the entrance hall she ran into the library and, though she had been gone almost four hours, she found Radclyffe sitting just where she had left him, still writing. He looked up.

“Well, madame. Did you have a pleasant drive?”

“Oh, wonderful, your Lordship! It’s a fine day out!” She walked toward him, begining to pull off her gloves. “We drove through St. James’s Park—and who d’ye think I saw?”

“Truthfully, I don’t know.”

“His Majesty! He was walking in the rain with his gentlemen and they all looked like wet spaniels with their periwigs soaking and draggled!” She laughed delightedly. “But of course he was wearing his hat and looked as spruce as you please. He stopped the coach—and what d’you think he said?”

Radclyffe smiled slightly, as at a naive child recounting some silly simple adventure to which it attached undue importance. “I have no idea.”

“He asked after you and wanted to know why he hadn’t seen you at Court. He’s coming to visit you soon to see your paintings, he says—but Henry Bennet will make the arrangements first. And”—here she paused a little to give emphasis to the next piece of news—“he’s asking us to a small dance in her Majesty’s Drawing-Room tonight!”

She looked at him as she talked, but she was obviously not thinking about him; she was scarcely even conscious of him. More important matters occupied her mind: what gown she should wear, which jewels and fan, how she should arrange her hair. At least he could not refuse an invitation from the King—and if her plans succeeded she would soon be able to cast him off altogether, send him back to Lime Park to live with his books and statues and paintings, and so trouble her no more.

CHAPTER FORTY–TWO

THE TWO WOMEN—one auburn-haired and violet-eyed, the other tawny as a leopard, and both of them in stark black—stared at each other across the card-table.

All the Court was in mourning for a woman none of them had ever seen, the Queen of Portugal. But in spite of her mother’s recent death Catherine’s rooms were crowded with courtiers and ladies, the gaming-tables were piled with gold, and a young French boy wandered among them, softly strumming a guitar and singing love-songs of his native Normandy. An idle amused crowd had gathered about the table where the Countess of Castlemaine and the Countess of Radclyffe sat, eyeing each other like a pair of hostile cats.

The King had just strolled up behind Amber, declining with a gesture of his hand the chair which Buckingham offered him beside her, and on her other side Sir Charles Sedley lounged with both hands on his hips. Barbara was surrounded by her satellites, Henry Jermyn and Bab May and Henry Brouncker—who remained faithful to her even when she seemed to be going down the wind, for they were dependent upon her. Across the room, pretending to carry on a conversation with another elderly gentleman about gardening, stood the Earl of Radclyffe. Everyone, including his wife, seemed to have forgotten that he was there.

Amber, however, knew very well that he had been trying for the past two hours to attract her attention so that he might summon her home, and she had painstakingly ignored and avoided him. A week had passed since the King had invited them to Court again, and during that time Amber had grown increasingly confident of her own future, and steadily more contemptuous of the Earl. Charles’s frank admiration, Barbara’s jealousy, the obsequiousness of the courtiers—prophetic as a weather-vane—had her intoxicated.

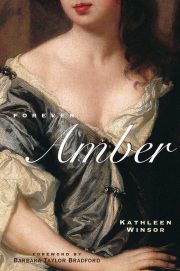

"Forever Amber" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Forever Amber". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Forever Amber" друзьям в соцсетях.