"But not for long, my lady."

"That we cannot tell. At all costs word must be sent to La Mouette, and she must leave the creek with the next tide."

"It would be more prudent to wait until night-fall, my lady."

"Your master will decide of course. Ah, William."

"My lady?"

But she shook her head, shrugging her shoulders, telling him with her eyes the things that she could never say in speech, and suddenly he bent down, patting her shoulder as though she were Henrietta, his funny button mouth twisted.

"I know, my lady," he said, "but it will come all right. You will be together again," and then because of the anticlimax of home-coming, because she was tired, because he patted her shoulder in his kind ridiculous way, she felt the tears running down her cheeks, and she could not stop them. "Forgive me, William," she said.

"My lady."

"So foolish, so unutterably foolish and weak. It is something to do with having been so happy."

"I know, my lady."

"Because we were happy, William. And there was the sun, and the wind, and the sea, and-loveliness such as has never been."

"I can imagine it, my lady."

"It does not happen, often, does it?"

"Once in a million years, my lady."

"Therefore I will shed no more tears, like a spoilt child. For whatever happens we have had what we have had. No one can take that from us. And I have been alive, who was never alive before. Now, William, I shall go to my room, and undress, and get into bed. And later in the morning you shall call me, with my breakfast, and when I am sufficiently prepared for the ordeal, I will see Sir Harry, and find out how long he intends to stay."

"Very good, my lady."

"And somehow, in some way, word must be sent to your master in the creek."

"Yes, my lady."

And so, with the daylight coming through the chinks in the shutters, they left the room, and Dona, her shoes in her hands and her cloak about her shoulders, crept up the stairway she had descended some five days earlier, and it seemed to her that a year and a life-time had passed since then. She listened for a moment outside Harry's room, and yes, there were the familiar snuffling snores of Duke and Duchess, the spaniels, and the heavy slow breathing of Harry himself. Those things, she thought, were part of the pattern that irritated me once, that drove me to absurdities, and now they no longer have any power to touch me, for they are not of my world now, I have escaped.

She went to her own room, and closed the door. It smelt cool and sweet, for the window was open on to the garden, and William had put lilies-of-the-valley beside her bed. She pulled aside the curtains and undressed, and lay down with her hands over her eyes, and now, she thought, now he is waking beside the creek, putting out his hand for me beside him and finding me gone, and then he remembers and smiles, and stretches, and yawns, and watches the sun come up over the trees. And later he will get up and sniff the day, as I have seen him do, whistling under his breath, scratching his left ear, and then walk down to the creek and swim. He will call up to the men on La Mouette, as they scrub the decks, and one of them will lower the rope ladder for him to climb, and another launch a boat to bring back the little boat and the supper things and the blankets. Then he will go to the cabin, and rub himself dry with a towel, glancing out of the port-hole on to the water as he does so, and presently, when he has dressed, Pierre Blanc will bring breakfast, and he will wait a little, but then because he will be hungry he will eat it without me. Later he will come up on deck and watch the path through the trees. She could see him fill his pipe, and lean against the poop rail, looking down into the water, and perhaps the swans would come back, and he would throw bread to them, idle, contented, filled with a warm laziness after his morning swim, thinking perhaps of the day's fishing to come, and the hot sun, and the sea. She knew how he would glance up towards her, if she came through the trees down to the creek, and how he would smile, saying nothing, never moving from the rail on the deck, throwing the bread down to the swans as though he did not see her. And what is the use, thought Dona, of going over this in my mind, for all that is finished, and done with, and will not happen again, for the ship must sail before she is discovered. And here am I, lying on my bed at Navron, and there is he, down in the creek, and we are not together any more, and this then, that I am feeling now, is the hell that comes with love, the hell and the damnation and the agony beyond all enduring, because after the beauty and the loveliness comes the sorrow and the pain. So she lay on her back, her arms across her eyes, never sleeping, and the sun came up and streamed into the room.

It was after nine o'clock that William came in with her breakfast, and he put the tray down onto the table beside her bed, and "Are you rested, my lady?" he asked. "Yes, William," she lied, breaking off a grape from the bunch he had brought her.

"The gentlemen are below breakfasting, my lady," he told her. "Sir Harry bade me enquire whether you were sufficiently recovered for him to see you."

"Yes, I shall have to see him, William."

"If I might suggest it, my lady, it would be prudent to draw the curtains a trifle, so that your face is in shadow. Sir Harry might think it peculiar that you look so well."

"Do I look well, William?"

"Suspiciously well, my lady."

"And yet my head is aching intolerably."

"From other causes, my lady."

"And I have shadows beneath my eyes, and I am exceedingly weary."

"Quite, my lady."

"I think you had better leave the room, William, before I throw something at you."

"Very good, my lady."

He went away, closing the door softly behind him, and Dona, rising, washed and then arranged her hair, and after drawing the curtains as he had suggested, she went back to her bed, and presently she heard the shrill yapping of the spaniels, and their scratching against the door, followed by a heavy footstep, and in a moment Harry was in the room, and the dogs with delighted barking hurled themselves upon her bed.

"Get down, now, will you, you little devils," he shouted. "Hi, Duke, hi, Duchess, can't you see your mistress is ill, come here, will you, you rascals," making, as was his wont, more ado than the dogs themselves, and then, sitting heavily upon the bed in place of them, he brushed away the marks of their feet with his scented handkerchief, puffing and blowing as he did so.

"God dammit, it's warm this morning," he said, "here I am sweating through my shirt already, and it's not yet ten o'clock. How are you, are you better, where did you get this confounded fever? Have you a kiss for me?" He bent over her, the smell of scent strong upon him, and his curled wig scratching her chin, while his clumsy fingers prodded her cheek. "You do not look very ill, my beautiful, even in this light, and here was I expecting to find you at death's door itself, from what the fellow told her. What sort of a servant is he, anyway? I'll dismiss him if you don't like him, you know."

"William is a treasure," she said, "the best servant I have ever had."

"Ah, well, as long as he pleases you, that's all that matters. So you've been ill, have you? You should never have left London. London always suits you. Although I admit it's been damned dull without you. Not a play worth seeing, and I nearly lost a fortune at piquet the other night. The King has a new mistress, they tell me, but I haven't seen her yet. Some actress or other. Rockingham's here, you know, and all agog to see you. God dammit, he said to me, in town, let's go down to Navron and see what Dona is up to, and here we are, and you a confounded invalid in bed."

"I am much better, Harry. It was only a passing thing."

"Well, I'm glad to hear that. As I say, you look well enough. You have a tan on you, haven't you? You're as dark as a gypsy."

"The illness must have made me yellow."

"And your eyes are larger than ever they were, dammit."

"The result of the fever, Harry."

"Queer sort of fever. Must be something to do with the climate down here. Would you like the dogs up on your bed?"

"No, I think not."

"Hi, Duke, give your mistress a kiss, and then get down. Here, Duchess, here's your mistress. Duchess has a sore patch on her back, and she's nearly scratched herself raw, look at that now, what would you do to her? I've rubbed in some pomade, but it does her no good. I've bought a new horse, by-the-way, she's down there in the stable. A chestnut, with a deuce of a temper, but she covers the ground quick enough. 'I'll give you a thousand for her,' says Rockingham, and 'Make it five thousand,' I tell him, 'and I might bite,' but he won't play. So the county's infested with pirates, is it, and robbery, rape and violence causing havoc amongst the people?"

"Where did you hear that?"

"Well, Rockingham brought back a story in town one day. Met a cousin of George Godolphin's. How is Godolphin?"

"A little out of temper when I saw him last."

"So I should think. He sent me a letter a while back, which I forgot to answer. And now his brother-in-law has lost a ship, it seems. Do you know Philip Rashleigh?"

"Not to speak to, Harry."

"Well, you'll meet him soon. I invited him over here. We met him in Helston yesterday. He was in a devil of a temper, and so was Eustick, who was with him. It seems this infernal Frenchman sailed the vessel straight out of Fowey harbour, right under the nose of Rashleigh and Godolphin. What infernal impudence, eh? And then off to the French coast, of course, with not a damned ship in pursuit. God knows what the vessel was worth, she was just home from the Indies."

"Why did you invite Philip Rashleigh here?"

"Well, it was Rockingham's idea really. 'Let's take a hand in the game,' he said to me, 'you're an authority, you know, in this part of the world. And we might have some sport out of it.'

'Sport?' says Rashleigh, 'you'd think it sport no doubt if you'd lost a fortune like I've done.'

'Ah,' says Rockingham, 'you're all asleep down here. We'll catch the fellow for you, and then you'll have sport enough.' So we'll hold a meeting, I thought, and collect Godolphin and one or two others, and set a trap for the Frenchman, and when we've caught him we'll string him up somewhere, and give you a laugh."

"So you think you'll succeed, Harry, where others have failed?"

"Oh, Rockingham will think of something. He's the fellow to tackle the job. I know I'm no damn use, I haven't got a brain in my head, thank God. Here, Dona, when are you going to get up?"

"When you have left the room."

"Still aloof, eh, and keeping yourself to yourself? I don't get much fun out of my wife, do I, Duke? Hi, then, fetch a slipper, where is it, boy, go seek, go find," and throwing Dona's shoe across the room he sent the dogs after it, and they fought for it, yapping and scratching, and returning, hurled themselves upon the bed.

"All right then, we'll go, we're not wanted, dogs, we're in the way. I'll go and tell Rockingham you're getting up, he'll be as pleased as a cat with two tails. I'll send the children to you, shall I?"

And he stamped out of the room, singing loudly, the dogs barking at his heels.

So Philip Rashleigh had been in Helston yesterday, and Eustick with him. And Godolphin too must have returned by now. She thought of Rashleigh's face as she had seen it last, scarlet with rage and helplessness, and his cry, "There's a woman aboard, look there," as he stared up at her from the boat in Fowey Haven, and she, with the sash gone from her head, and her curls blowing loose, had laughed down at him, waving her hand.

He would not recognise her. It would be impossible. For then she was in shirt and breeches, her face and hair streaming with the rain. She got up, and began to dress, her mind still busy with the news that Harry had given her. The thought of Rockingham here at Navron, bent on mischief, was a continual pin-prick of irritation, for Rockingham was no fool. Besides, he belonged to London, to the cobbled streets, and the playhouses, to the over-heated, over-scented atmosphere that was St. James's, and at Navron, her Navron, he was an interloper, a breaker of the peace. The serenity of the place was gone already, she could hear his voice in the garden beneath her window, and Harry's too, they were laughing together, throwing stones for the dogs. No, it was done with and finished. Escape was a thing of yesterday. And La Mouette might never have returned after all. The ship might still have lain becalmed and quiet off the coast of France, while her crew took the Merry Fortune into port. The breakers on the white still beach, the green sea golden under the sun, the water cold and clean on her naked body, and after swimming, the warmth of the dry deck under her back, as she looked up at the tall, raffish spars of La Mouette stabbing the sky.

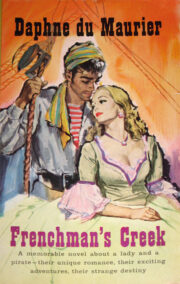

"Frenchman’s Creek" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Frenchman’s Creek". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Frenchman’s Creek" друзьям в соцсетях.