"You had best be very sure of your facts, sir, for if you slander my uncle, you will hear from my solicitor."

I flounced out of the parlor in high dudgeon. No words followed me about sparing my family shame. So much for his fine claim! I ran upstairs to tell Mama what had happened. Her agitation was as great as my own. We enjoyed a quarter of an hour's heated tirade against Lord Weylin, then decided to send for a pot of tea, as it was clear we would not be getting any sleep that night.

By the second cup, we had calmed down sufficiently to speak sensibly. “If it were true,” Mama said, fingering her chin to aid concentration, “how did Barry come to discover Mr. Jones was Lady Margaret's by-blow, as it seems Mr. Jones did not know himself? How did Barry suspect she ever had this illegitimate child? Do you think someone in Ireland was the father?"

Then the truth struck me with the force of a blow. “Good God! Could Andrew be Barry's son?"

"Barry was the best-looking of all his set, no denying."

"Why the devil did he not marry her?"

"Perhaps he did not know of her condition. Lady Margaret was still in Ireland when he went to India. I wonder how he learned of it. I daresay she wrote and told him, but it takes such an age for a letter to reach India, and then for him to have to sail back home… It would be too late. The child would already be born. I really think that is what happened, Zoie. Why else would Barry be at such pains to see the lad was taken care of? And it would explain what happened to his own money as well. He gave it to Andrew, as he should."

I could not like this version of the story either. It put Barry in a bad light, ruining a young lady, then merrily running away and leaving her to her fate. As I thought over the tone of his letters to Lady Margaret, I thought he took pretty high ground, blaming her for abandoning their son when he had abandoned both of them. He should have been begging her forgiveness. But that is the way. Two people misbehave, and it is the lady-and the child-who bear the brunt of it.

"We shan't tell Lord Weylin what we think,” Mama said. “It is all done and over with now. No point slandering the dead."

"What of the living, Mama? Weylin plans to get the money back from Andrew Jones. He thinks Jones is an impostor. I fear we must tell him the truth."

"Plague of a man. Why can he not leave well enough alone? They cannot put us in jail, can they, Zoie? We have done nothing wrong-but it would be wrong to say nothing when we know the truth."

"We do not actually know it,” I said uncertainly.

"In my bones, I know it,” Mama said wearily. “I always wondered that Barry showed no interest whatsoever in Lady Margaret when he came to stay with us. She was still a handsome lady, but he never looked within a right angle of her. He did not want me to notice anything between them, you see. What he should have done was to marry her-belatedly, to be sure, but better late than never. A scoundrel to the end, and he was such a nice, jolly boy."

"You must tell Weylin, Mama. He plans to go to London early tomorrow and begin making trouble for Mr. Jones."

"I shall mention it, but of course, we have no proof. Very likely he will try to get Barry's five thousand into the bargain. That belongs to my nephew."

That “nephew” came out as if Mama had been saying it forever. How quickly she had accepted the idea. If her suspicions were true-and she knew Barry better than anyone else did-then I had a new cousin. I was curious to see what Cousin Andrew was like. I was also apprehensive to consider meeting Lord Weylin with this new version of the story, which threw an even more degrading light on Barry.

In the confusion of our discussion, I had overlooked the fact that Mrs. Sangster, at the post office, had not recognized Barry. If he had been staying at Lindfield with Lady Margaret, she must have seen him. Perhaps he had stayed close to the house. Then, too, I had showed her an altered sketch, and said he was a clergyman. She would hardly think of connecting a servant with a clergyman. Would she recognize him without his clerical collar and the mustache? That could easily enough be checked.

Cousin Andrew-he was Weylin's cousin, too. Odd that we were now connections, just when he must be wishing he had never heard of us.

Chapter Fifteen

As I lay in bed staring at the invisible ceiling, I reflected on the curious situation we had uncovered.

I liked to think that Andrew, Lady Margaret, and Barry had enjoyed some happy days at Lindfield. I understood now why they had all stuck close to the house. They just wanted to be together, away from the prying eyes of the world. Lady Margaret doted on the boy, the locals said. That suggested that she, at least, had enjoyed having her son back. I could not like that my uncle was sunk to posing as their servant. As Lady Margaret had become Mrs. Langtree, why could he not have been Mr. Langtree, and Andrew their son? Did Andrew know he was their son, or did they tell him he was “Mrs. Langtree's” nephew?

Both Mama and I looked like hags when we went down to the private parlor in the morning. A sleepless night is enough to destroy a lady's face, and when shame and worry are added on top, it is hard to keep up any countenance at all. I was not too unhappy to find the parlor unoccupied.

When we entered, the waiter said, “His lordship had breakfast early and has left for London. He said to inform you that he would be gone for a few days, madam."

My first reaction was relief. The inevitable had been staved off temporarily. Then I thought of Cousin Andrew, and knew we could not let Weylin go about his business unchecked.

As soon as we had ordered breakfast and got rid of the waiter, I said, “We must stop Weylin, Mama."

"I shall write and tell him what I believe to be the truth, Zoie, for I cannot face a trip to London at this time."

"Would you not like to see Cousin Andrew?” I asked.

"I would, but I am less eager to see Lord Weylin. Best to tell him the truth in a letter, and let him digest it before we have to see him again."

The letter was much discussed over breakfast. After our plates were cleared away, we asked for pen and paper, and Mama wrote her explanation in a simple, straightforward way. She expressed regret, and the hope that Lord Weylin would not treat Mr. Jones harshly. Whatever of the others, he, at least, was an innocent victim. When we were satisfied with the letter, she gave it to the waiter for posting to Weylin's London residence.

"Can we go home now?” Mama asked weakly.

I would have liked to take an unaltered sketch of Barry to Mrs. Sangster for confirmation that he was Mrs. Langtree's servant, but Mama looked so worn, I could not ask her to stay longer. We called our carriage. You may imagine my chagrin when I saw that wretch of a Steptoe sitting saucily on the box beside Rafferty. Steptoe lifted his hat and said, “Good morning, ladies."

When Rafferty let down the stairs, he said to Mama, “He asked if he could hitch a lift. I hope you don't mind, ma'am?"

"It is no matter,” Mama said. She was beyond caring.

We did not talk much on the way home. I noticed Mama's frown dwindle to a bemused smile about halfway along the road, and knew she was thinking of Cousin Andrew. I thought of him, too, wondering what he was like, and whether the Weylins would acknowledge him. Of course Mama would. Irish families are close, and if the Duke of Clarence can vaunt his dozen or so by-blows, why should we hang our heads in shame at claiming one?

"We shall invite my nephew to Hernefield for a visit after this is all cleared away, Zoie,” Mama said as the carriage arrived home. “A pity you were in such a rush to dismantle the octagonal tower. He might have liked to use his papa's room."

I had lost my enthusiasm for art lessons since learning Count Borsini was a fraud. I would dismiss him, and continue with my work unaided, but as the tower was already dismantled, I would use it as my studio. It was good to be home, even if the future was uncertain. I was even happy to have Brodagan jawing at us again.

"I see Steptoe is back like a bad penny,” she said. “I hoped we'd seen the back of him.” She said a deal more; there was no fault in the world but Steptoe had it. “Where has he been? That is what I would like to know, and I will. The gander's beak is no longer than the goose's when it comes to rooting out the truth. If it was a wrong he was doing you, melady, it'll come back on him in time."

There would be a breaking and bruising of bones belowstairs, but I had other things to worry about. I went straight up to the attic and searched through every box and bag Barry had brought home with him, hoping to find some confirmation or contradiction of Mama's suspicions.

Lady Margaret must have answered those letters he had written to her. She may even have written to him when he was in India. That was my major activity for the next two days. After going through everything twice, I was convinced Barry had not kept the letters, or anything else of an incriminating nature.

His death had not been sudden. He had faded away slowly over a period of two weeks-ample time to be rid of the evidence of his past sins. Barry had, presumably, told Andrew of his mother's passing. I wondered how the poor fellow had heard of his father's death. It seemed wrong that the newly found son had not attended the funeral of either parent. As I thought of these things, Andrew began to seem like a real person to me, with worries and troubles of his own.

Who had raised him? Was he what we call a gentleman? He had been teaching in a boys’ school, so at least he had been educated. It was difficult to form any idea of his appearance. Lady Margaret was blond and soft-featured and plump. Barry was tall and dark and lean. Whatever the physical attractions of his youth, by the time I met Barry, he had hardened to a somewhat bitter man, with his skin tanned by the tropical sun of India.

Yet there had been occasional flashes of a warmer personality lurking below the surface. Sometimes when we had company, Barry would expand a little on his experiences in India, especially if the company included ladies. And when he chaperoned my lessons with Count Borsini, he and the count often fell into lively conversation, as two well-traveled gentlemen will do. Barry used to speak of his Indian adventures, and Borsini told tales of his life in Italy.

It would soon be time for another lesson with Borsini. To avoid it, I wrote to Aldershot and told him I no longer felt the need of his tutelage. I thanked him very civilly for past help, but made quite clear the lessons were over.

Steptoe continued on with us, without any change in salary. He was a reformed character, and we were too distracted to want the bother of finding a replacement. By Sunday, Weylin had still not returned from London. The length of his visit caused considerable worry at Hernefield. He had not deigned to reply to mama's letter, so we had no idea what course he was following. It did not even occur to us to apply to Parham for information. We had no idea whether he had informed his mama what was afoot.

On Monday the painters came to paint my studio. I went upstairs with them to give instructions. Brodagan could not miss the opportunity to order two grown men about, and went with us. She cast one look at the floor and said, “I told Steptoe to see this carpet was rolled up and put away. They'll destroy it with paint drops."

"It hardly matters, Brodagan. It is already a shambles."

"A shambles, is it? It is a deal better than the wee scrap of rug in my room."

"We'll not harm it, misses,” the painter in charge assured her, “for we'll lay this here tarpaulin over it.” As he spoke, he took one end of the tarpaulin, his helper the other, and they placed it carefully over the shabby old carpet.

They opened the container of paint and began stirring it up. It looked a very stark white. I left them to it, and went belowstairs just as Mama was putting on her bonnet.

"I am driving into Aldershot, Zoie,” she said. “I want to get new muslin for Andrew's sheets. And perhaps new draperies for the blue guest room. They have got so very faded."

"We are not sure he will come, Mama, but the new sheets and even draperies will not go amiss. I shall stay home to keep an eye on my studio. This paint looks very cold. I may change the shade after they have done half a wall."

"I shan't be long."

She left, and I took my pad to the garden to try my hand at sketching the gardener, who was working with the roses in front of the house. As there was no convenient seat, I sat on the grass and studied the gardener a moment, choosing the most artful pose for my sketch. It would be a full-length action drawing. He changed position so often that it was difficult to draw him. As he only gave us two afternoons a week, I did not like to disrupt his work and ask him to stand still.

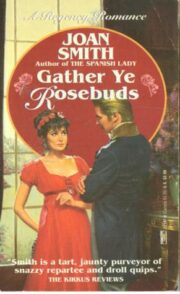

"Gather Ye Rosebuds" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Gather Ye Rosebuds". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Gather Ye Rosebuds" друзьям в соцсетях.