"That is another possibility. I had quite convinced myself of it-until Steptoe entered the picture. You recall this evening Borsini displayed an unholy eagerness to get into your late uncle's room to look for something. Something he did not wish us to see."

"And what would this item be? A deathbed confession written by my uncle?” I asked satirically.

"Hardly that, I think. More likely they had a written agreement of some sort. Or perhaps letters relating to the scheme. The possibilities are endless. The missing item might be a key to a safety box. That would explain why it is of value to Borsini, who knows where the box is, and useless to Steptoe."

"I thought Borsini and Barry both had a key to this imaginary safety box."

"Borsini may have lost his. I am just suggesting possibilities."

"I have noticed you are quick to suggest any possibility that makes my uncle into an ogre and a thief."

"Cut line, Zoie. I learned, in London, why your uncle retired early. Funds missing from the EIC, was it not? You are defending the indefensible."

"You have been checking up on my uncle? Dragging our name through the mud! My uncle did not steal that money. One of his underlings took it. He told us all about it. They caught the man, and got the money back. My uncle retired voluntarily, with his full pension. They would not have given him his pension if he had robbed them."

"They got a part of the money back. McShane was in charge. He was either involved, or a demmed bad manager, as I said. Demme, I don't see why you are so angry. I am not suggesting McShane's character reflects in any way on you. He conned you and your mama. No disgrace in being a victim. Every family has its dirty dishes. My own Cousin Albert embezzled a fortune from his friends on forged mining stocks. Scratch any rich man and you will find a scoundrel; if not in the present generation, you do not have to go far back in history. I thought we were working on this together."

"No, Weylin. It is clear to me you are working to turn your aunt into one of those innocent victims, to my uncle's discredit."

"You won't admit Borsini is a crook, in other words,” he said. “That is what this is all about. You have fallen for his smooth lies. I have heard him at work on Mama. I know how he operates. Never has he seen such lustrous eyes, such a complexion, like rose petals. Can she really hear, with those dainty ears, like seashells? The man is nothing but a gigolo. I shall kick him out the door as soon as we find this item he and Steptoe are looking for. And I'll have back my aunt's fortune as well, to give to her real son."

"You don't know that Borsini is not the real son,” I said. I would have said more, were it not for those familiar old compliments. I daresay Lady Weylin would be pulling her hair back in a Grecian knot and donning a toga before long.

I kept remembering, too, how well Borsini and Uncle Barry got along together. In the inclement weather, I used to send the carriage to Aldershot for him. As often as not, Barry would go along for the ride. I had thought he was just bored in his retirement, but now I began to wonder.

Every few months, Borsini would miss a lesson. I had taken no special note of the times, but it did seem to be about once a quarter. He had missed the lessons because he had been at Tunbridge Wells, posing as Andrew Jones. The timing of Borsini's entry into my life, and the fact that it was Barry who introduced us…

Weylin said, “If Borsini is their son, why does he not say so? And why is he looking for that certain something, offering to pay a hundred pounds for it? That is not the behavior of an innocent man, Zoie."

"If there is anything in this house to prove it, I shall find it, if I have to tear down the walls and pull up the floorboards."

"I shall come over early tomorrow morning. The place to begin is in your uncle's room."

"My uncle used the octagonal tower-that is now my studio. It has been stripped bare. His personal effects were taken to the attic. Mama and I-and Steptoe-have been through them a dozen times."

We sat a moment, pondering this problem. Weylin said, “There is more than one way to skin a cat. Borsini has a past, and we won't have to go all the way to Italy to discover it. I shall send a man to Dublin to check into this boys’ school. There will be some record of a teacher leaving unexpectedly five years ago. I daresay he has a full set of parents of his own, and a birth certificate to prove it. But first we'll have one more go at the studio, and the attics."

Something in me disliked to see my old friend Borsini disgraced. I knew his charm was only a second-rate thing. I had never really believed the palazzo in Venice, or the vineyards, but he had been kind and thoughtful in his way. He used to bring little bouquets of violets in the spring, and say he wished they were orchids. He always remembered any personal thing I told him. When I said I liked Thomas Gray, he had got a copy of his poems at the circulating library and read them. He used to send a card on my birthday, with a poem so awful, I knew without being told that he had written it himself.

He had always been respectful to me. There had been several occasions when he might have made improper advances. He always behaved like the perfect gentleman. His compliments on complexion and ears were given shyly, while he worked. I knew they were like cologne, to be sniffed and enjoyed, not taken seriously. He never once touched me in any familiar way. Other than the occasional mention of the family estate in Italy, he was modest and unassuming. If he was a thief, it was my uncle who had seduced him into it. I could not like to see poor Borsini take the brunt of it, and that was exactly what Weylin had in mind.

"You need not trouble yourself to come and search, Weylin,” I said, and stood up to leave. “I shall do it myself."

Weylin rose and looked at me through eyes narrowed to slits. “And conceal the evidence?” he said. “You are letting your partiality for Borsini lead you astray."

"He is not a bad man, whatever you say."

I did not expect such an outburst. Weylin flew into a towering rage. “So he has been sweet-talking you all the while, has he? Oozing his pseudo-Latin charm on you. Has he screwed himself to the sticking point? Or have you, like my aunt, given yourself without benefit of marriage?"

When I figured out what he meant, I lost the last vestige of control. I raised my hand and struck him a resounding blow on the cheek. The slap echoed on the still night air, with Weylin's gasp of surprise coming after it, the echo of an echo.

"How dare you! I'll have you know, Lord Weylin, Count Borsini is a gentleman. He may not have any right to his title, and he may not have a family mansion behind him, but he-"

"Are you engaged to him?” he said, cutting into my tirade. “You have lost your mind, Zoie. When an engagement must be kept under wraps, that should be enough to tell you there is something wrong with it."

"I am not engaged to him! He has never touched me-in that way, I mean. We are friends."

I watched as the fury subsided to anger, and softened further to embarrassment. “I am happy to hear it,” he said, quite mildly. “I admit I rather liked him myself before-"

"Before you took the notion he was posing as Andrew Jones?"

"Oh no. I suspected that earlier, which is why I took him to Parham, to pick his brains a little.” He stood, looking ill at ease, a completely new posture for Lord Weylin. “I am sorry if I offended you, Zoie."

"And I am sorry I attacked you, but I am not accustomed to being accused of loose and wanton behavior. It strikes me you have a poor notion of my character, sir. First you thought I was stealing that stupid little pot at Parham."

"A Ming vase!"

"I didn't know that, did I? We have one exactly like it in our spare room."

"Not exactly like it, I think. You have your blind spots as well, you see.” His hands rose and seized my wrists. “Why do you think I flew into a pelter when you leapt to Borsini's defense?” he said, in a husky voice. His fingers eased up my forearms until they were holding me in a tight grip, and all the while his head was inching slowly to mine, as if drawn by an inexorable force.

My throat felt swollen. When I spoke, my voice had that same choked sound as Weylin's. “I do not see it is any of your business,” I said weakly.

"Blind as the proverbial bat,” he said softly, and seized my lips for a scalding kiss, there in the moonlight, with the cloying scent of roses around us-and just a whiff of the stable, too, from his jacket. Weylin was no uncertain, teenaged Romeo. He did not woo like a babe, but like a fully grown man. I felt the passion in him, and was aware of an answering force rising like a tide inside me, matching every pressure of body and lips. His arms pressed me against his hard chest, and my hands found their way to his neck. My fingers moved possessively through his crisp hair.

He moved one hand to rest against my throat, the fingers splayed so they touched my shoulder. His moving fingers felt fevered. I could feel my pulse throb against them with every beat of my heart. A heat grew between us; flames licked along my veins and rose in a delirium to my head, robbing me of sense.

Was this how Lady Margaret had lost her virtue? I did not know whether she deserved pity or envy. Through the swirling mist of passion, I remembered Weylin's hint that I had given myself to Borsini. Weylin had made no declaration of love, or of honorable intention. Was he trifling with me? I felt my body stiffen involuntarily. The heat cooled to a chilling anger. I pulled away and glared at him.

"Don't look at me like that!” he said gruffly. “If I got a little carried away, it was not all my doing, Zoie."

I waited to hear the more interesting words I had been hoping for. When they did not come, I said coolly, “You had best go now, Weylin."

"There is no hurry.” He tried to pull me back into his arms. I stepped back with a twitch of my skirts.

He said, “What time shall I come in the morning?"

"I shall let you know if I discover anything."

"Nine o'clock. I shall be here at nine.” He looked all around the garden, inhaling the scent of roses. Then he looked up at the moon and smiled. “It seems a shame to waste that moon,” he said, with a quizzing smile.

I was ready to blame the moon for half my behavior. “It will light your way home,” I told him.

He stood a moment, looking at me in an assessing way. My stiff demeanor told him the lovemaking was over. He accepted it, whistled for his mount, and left with a wave.

I went back inside, determined to be in the attic by seven o'clock tomorrow morning for a private search. And I would have Brodagan or Mama come upstairs with us when Weylin arrived at nine, if I had no luck before that, to keep him in line.

I returned to my lamp chair and my book of poetry, to review our meeting in the garden. How Mrs. Monroe would stare if she knew what brought that smile to my face! Put on my caps indeed! Put on a tiara was more like it. That embrace in the garden told me Weylin loved me, and I meant to see that he did the proper thing about it.

Chapter Twenty

Despite my intention, I did not have a root through the attic trunks before Weylin's arrival the next morning after all. Brodagan came down with a toothache in the night, and when Brodagan has the toothache, they hear of it in Scotland and Wales. Morpheus himself could not sleep for the moaning. Servants raced through the halls bringing her oil of cloves and camphor, tincture of myrrh and friar's balsam and brandy-all to no avail. When it became clear that this was one of Brodagan's major toothaches, as opposed to the minor ones that cure themselves after a toothful of brandy, I knew my duty, and I did it.

I got out of bed at two o'clock in the morning and went belowstairs to prepare her a posset with a few drops of laudanum, to let the poor soul rest. I would insist she have that distressed tooth removed in the morning.

Steptoe came to the kitchen to inquire what was amiss. He was wearing a dressing gown that belonged to a dandified lord. It was green silk with gold tassels on the belt. On the pocket some family crest was embroidered. Either Pakenham's or Weylin's, no doubt. I told him of Brodagan's trouble. He stirred up the moldering embers in the stove, and between us we got the milk heated. There was enough for two, and I took the pan with me, planning to have the second cup myself, without the laudanum. I added a few drops of the medicine to Brodagan's cup and went upstairs.

Brodagan lay in bed with a hot brick against her cheek, cushioned with a wad of flannelette. Without her headpiece, and with her face shriveled in pain, she looked no more formidable than young Mary. Mary was with her, warming another brick at the grate, to replace the one in use when it cooled off.

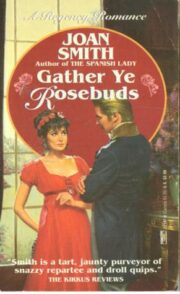

"Gather Ye Rosebuds" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Gather Ye Rosebuds". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Gather Ye Rosebuds" друзьям в соцсетях.