"Thank you, Brodagan. I shall deal with Mrs. Chawton. I am sorry you had the inconvenience of looking after the door."

"Your apron, Brodagan! You have singed it,” Mama said.

Brodagan stared placidly at her charred apron. “There's two night's work and two shillings of me pittance of money gone up in flames, for I'll not disgrace you by being seen in this ruin again, meladies. It'll make dandy rags,” she said, and sailed out. Of course, she would cut off the burned edge and have Mary rehem it, but one did not introduce reality into one of her Celtic tragedies.

"I shall go up and bring Steptoe down for you to dismiss him, Mama,” I said.

Her pretty face pinched in displeasure. “Why don't you speak to him yourself, dear? You handle him better than I."

Mama dislikes trouble nearly as much as Brodagan relishes it. I fall in the middle, and am the go-between for such jobs as this. I did not look forward to confronting Steptoe, but I did not dread it either. I found him in the tower room, as Brodagan had said. He was separating my uncle's belongings into two boxes, one for the better items, one for the worn garments.

He looked up boldly. “I'll keep this lot for myself,” he said, pointing to the box of good clothes. “My tailor can do something with these jackets."

"My tailor"-as though he were a fine gent! It was the little goad I needed to lend sharpness to my words. “I have just returned from Parham, Steptoe. I told her ladyship where the diamonds were found. No legal action will be taken."

He looked sulky, but not so chastened as he ought. “I am afraid we cannot see our way clear to increasing your salary. Naturally you will not want to remain with us at your present wage. You may consider yourself free to look for another position. It will be best if you not use us as a reference. Let us say two weeks, to give us both time to make other arrangements."

His snuff brown eyes narrowed. “I might be able to get along on my present wage for the meanwhile,” he said.

"You force me to remove the gloves, Steptoe. Your services are no longer required."

His reply was not apologetic, but aggressive. “I never took nothing from you! You can't say I did."

"I did not accuse you of stealing the spoons."

"If it's that little Chinese jug from Parham you're referring to, I never took it. It got broken, and if one like it turned up at the antique store, it's nothing to do with me."

It was foolish of him to actually tell me why he had been released from Parham. Nothing was more likely to vex Lord Weylin than tampering with his porcelains. “Two weeks, Steptoe,” I said, and turned to leave, happy to put the unpleasant incident behind me.

"I wouldn't do that if I was you, miss,” he said, with a nasty smile in his voice. I turned and looked a question at him. “I've a mate at Tunbridge Wells,” he said.

"What of it?"

"I go there on my holidays and days off. Interesting, what you see at Tunbridge."

"If you have something to say, Steptoe, say it."

"I'm not one to go rashly hurling accusations, like some. But I know what I saw at Tunbridge, and I know who I saw-the weekend Lady Margaret's necklace was stolen."

I felt my body stiffen at his words. “Are you referring to my uncle?"

His lips drew into a cagey grin. “Will you still be wanting me to leave, miss?"

"There will be no salary increase,” I said, and left on that ambiguous speech.

Naturally I darted straight down to the saloon to tell Mama what had happened.

Mama paled visibly. “He'll tell the world Barry was there when the necklace was stolen! Do you think it is true, Zoie?"

"Barry had the necklace. Lord Weylin asked whether I was certain Uncle did not go to Tunbridge. We don't really know where he went. We have only his word for it."

"My own brother, a common thief!"

What bothered me more was what Lord Weylin would say if Steptoe told him. It was intolerable to be in the clutches of a creature like Steptoe. I had been looking forward to Borsini's visit, but this new development robbed it of all pleasure.

I discussed the matter with Mama over lunch, and we decided we must go over all Barry's papers to see if we could find any evidence of his having been at either London or Tunbridge Wells. He might have receipts from hotels, or his bankbook might turn up interesting sums. The deposits should be no more than his pension from John Company. If larger deposits appeared, we would know the worst. We also hoped to discover what he had done with his ill-got gains, for when he died, his total estate of thirty-nine pounds went to Mama.

I wrote to Borsini, putting off his visit, and spent the afternoon in the attic with Mama, rooting through boxes of old letters and receipts. There was nothing to indicate any untoward doings. The recent bankbooks held only a record of the quarterly pension deposits. Uncle took nearly the whole sum out as soon as it went in. He kept a running balance in the neighborhood of fifty pounds. Whatever he spent the rest on, he must have paid cash.

Taking into account the small sum Mama took from him for room and board, though, he seemed to have spent a great deal of money. He did not indulge himself in a fancy wardrobe. He had a couple of decent blue jackets, one good evening suit, and one old-fashioned black suit that he never wore. It was quite ancient. He did not set up a carriage, or even a hack. On the few occasions when he rode, he borrowed my mount. He was not the sort to spend his nights in the taverns, or eat meals out. Mama thought it was the rumors of his Indian misadventure with the account books that kept him to himself. He felt it keenly.

Mama had perched on the edge of a trunk. She called, “Look at this, Zoie. This is curious.” I went to see what had caught her interest. It was a bankbook dating back to the time of Barry's arrival at Hernefield. “He came home with five thousand pounds! It was withdrawn from the bank the week after he got here. What did he do with it?"

I stared at the crabbed entries, counting the zeroes to make sure it was five thousand, and not five hundred, or fifty thousand. Nothing seemed impossible, but it was indeed five thousand. We puzzled over it awhile, until a dreadful apprehension began to form.

"Was he paying someone off, being held to ransom?” Mama suggested.

"Steptoe!” I exclaimed.

"Steptoe was still with the Pakenhams then. He only came to us three years ago. We cannot blame Steptoe, much as I should like to."

"What is the date?” I said, running my eye along the left-hand column. “May the fifteenth, 1811. About the time Lady Margaret's necklace was stolen. Mama, Uncle Barry bought the necklace! And here we were in a great rush to give it back to the Weylins."

She clapped her two hands on her cheeks. “Oh dear, and they will never believe us. I can hardly believe it myself. Five thousand pounds thrown away on that ugly old thing."

"And to think I humbled myself to them, apologizing and listening to Lady Weylin accuse me of chasing after her son."

"Why did Lady Margaret say it was stolen?” Mama asked. “The thing was not entailed. Her husband gave it to her as a wedding gift, so if she wanted to sell it, she could. Barry must have bought it in all innocence from whoever stole it."

"Why would he do that? It is not as though he got it at a bargain price. The necklace would hardly be worth five thousand, and to buy it from some hedge bird on a street corner-it makes no sense. If he wanted a diamond necklace for some reason, he would have bought it from a reputable jeweler."

After considerable discussion, we had gotten no further toward solving the mystery.

"Steptoe knows something about this,” I said, and rose to march downstairs and confront him.

He was still in the tower room, which struck me as highly suspicious. As there was nothing there worth stealing, however, I only told him his duties were belowstairs, before speaking of the more important matter. I chose my words carefully. It was not my intention to tell him anything, only pick his brains to discover what he knew.

I jumped in without preamble. “I want to know the meaning of your cryptic reference to Tunbridge Wells, Steptoe,” I said.

He looked at me with the face of perfect innocence, but with that sly light beaming in his eyes. “Tunbridge Wells, madam? A fine and healthy spot. I often go there to take the waters. I believe I mentioned it to you earlier."

"You implied seeing my uncle there. What was he doing?"

"I did not say I had seen Mr. McShane, madam. You must have misheard me."

"Then you did not see him?"

"Oh, I did not say that either, miss.” The subtle shift from “madam” to the demeaning “miss” did not pass unnoticed. “It might come back to me anon."

There was obviously no point quizzing him further. He knew something, but he was holding on to it for future mischief.

"Why are you wasting your time up here? Go downstairs. That is what we are paying you for."

"Certainly, miss."

His bow was a perfect model of impertinence. I wanted to run after him and kick him, but uncertainty held me in check. The devil knew something that would redound to my uncle's discredit, or he would not be so brass-faced. I went back to the attic and reported my failure to Mama.

My mood could hardly have been worse when Steptoe came tripping up to the attic ten minutes later. His bold eyes took a close look at what we were doing before he spoke. “Lord Weylin to see you, Miss Barron."

"Lord Weylin!” Mama exclaimed. “What can he want?"

"He did not say, madam,” Steptoe said. “Shall I tell him you are indisposed, Miss Barron?"

It was what I wanted to say, but I would not give Steptoe the satisfaction. “Certainly not. I shall be down presently. Pray show his lordship into the saloon while I wash my hands."

"I have already done so, madam."

I gathered up my uncle's papers to take to my room, safe from Steptoe. “Come down with me, Mama,” I said. “I cannot meet Weylin alone."

"Why, Zoie,” she laughed, “it is not a courting call. It is only business. At your age there can be no impropriety in meeting a gentleman alone."

"Of course it is not a courting call!"

"Well then-I shall just poke about up here and see what else I can find. Leave those papers with me."

I left her to it and went to my room to freshen up.

Chapter Six

That killing phrase, “at your age,” has begun finding its way to Mama's lips too often to suit me. It seems only yesterday the phrase that guided my actions was “when you are a little older.” When had I become old enough to be my own chaperon? The awful answer is that the point had not arisen in recent memory, because no gentleman had tried to get me alone.

Naturally I knew Lord Weylin had only come to discuss the curst necklace, but that did not mean I must greet him with dusty hands and cobwebs in my hair. With the memory of his sartorial elegance still fresh in my mind, I was tempted to change out of the three-year-old sprigged muslin I had put on for rooting in the attic.

By the time I had washed up and brushed away the cobwebs, ten minutes had passed. I could not like to leave him waiting any longer, and went belowstairs in the old sprigged muslin.

Our saloon, which is not honored with a formal name like the Blue Saloon at Parham, suddenly seemed cramped and shabby. Lord Weylin's boots shone more brightly than our mirrors; his jacket had more nap than our carpets. I wished I had changed my gown, but as I had not, I went forward to greet him.

He rose and bowed. “Miss Barron. You will be wondering what brings me pelting to see you so soon after your visit.” If he took any interest in either my hair or my gown, he concealed it well. His glowing eyes displayed a keen interest in something, but that something was not Miss Barron, nor her lack of a chaperon either.

"I am sure you are welcome any time, milord, but I expect I know why you are here. It is about the necklace, of course."

His thoughtless “Of course” confirmed that no other reason for coming had so much as entered his well-barbered head. “The strangest thing!"

My heart plunged. He had heard something to Barry's discredit! Steptoe had sent him a note, or-For a moment, Lord Weylin faded to a black cloud, which slowly dissipated to reveal my caller, staring at me in astonishment. I did not quite tumble over, but I was reeling.

He hastened forward to assist me into a chair. “What an idiot I am! I've frightened you to death. Let me get you a glass of wine. You're white as paper."

He bustled about, pouring the wine and handing it to me. I sipped and was glad for the warmth it brought to my shaken body. “A weak spell. I cannot think what came over me,” I said. “Pray help yourself to a glass of wine, milord.” I wished we had set out a better wine. There were still a few bottles of Papa's good wine in the cellar, but the sherry on the table was first cousin to vinegar. He did not take any, however. His interest was all on the necklace.

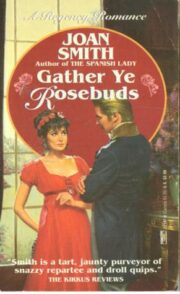

"Gather Ye Rosebuds" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Gather Ye Rosebuds". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Gather Ye Rosebuds" друзьям в соцсетях.