He drew it out of his pocket and placed it on the table in front of me. With the recent discovery of Uncle's financial doings in my head, I jumped to the conclusion that he had discovered in some manner that Barry had bought it, and he was giving it back to us. “How did you find out my uncle bought it? You must have been looking through your aunt Margaret's accounts, as I have been looking into my uncle's."

His brows rose in gentle arcs. “I beg your pardon? Are you saying your uncle bought the necklace?"

"I… well, perhaps.” Then I said more firmly, “Yes."

"Will you explain more fully? I do not quite understand."

I explained about the five thousand pounds Uncle had come home with, and taken out of his account at around the time the necklace had disappeared.

"Good God!” he exclaimed. “It looks as though my aunt is the thief, for this thing she sold him is glass."

"You mean it is not real diamond?"

"Mama thought it did not sparkle as it should. I tried cutting a windowpane with it. The edge of the stone crumbled without making a dint in the windowpane. I rushed it straight into the jeweler in Aldershot. Stacey confirmed that the thing is glass. Worth five or ten pounds."

I was stunned into temporary silence. When I looked at the necklace again, it seemed to have lost its luster. It looked common, cheap. I said, “So your aunt never had a diamond necklace at all?"

"She had one, all right. She took it to Stacey to be cleaned shortly before it was stolen. This is a copy. Mama did not know of its existence, nor did I, though it is not uncommon for ladies to have copies made of their jewels."

"And the real diamonds-they are still missing?"

"Yes, along with a few other baubles. Just trifles really. A garnet brooch, and an opal ring. The more valuable Macintosh jewelry was entailed on Macintosh's son."

"Your aunt did not report the other items stolen?"

"No, which is odd, for she certainly made a fine ruckus when the necklace was taken. I confess it is all a complete mystery to me. And now you say five thousand pounds of your uncle's money has vanished as well?” Lord Weylin displayed the keenest interest in all of this. I did not think he was really concerned, or worried about the jewelry, but just interested in a bizarre little mystery.

"Actually it vanished shortly after he came to us."

"Remind me, when was that, exactly?"

"He withdrew the money the fifteenth of May, 1811.” I looked to see if the date suggested anything to him.

"About the time my aunt's necklace disappeared-which is why you thought he'd bought it, of course. And no great bargain either. The thing was not insured, but it had been evaluated for insurance purposes at four thousand pounds. My aunt did not renew the policy as she so seldom wore it, and felt it was safe at Parham. When one takes into account that Mr. McShane would be called a thief if he ever produced the necklace, it begins to look as though his purchasing it is not the answer."

"He would never have bought it under those terms. Your aunt would not have claimed it stolen if she had sold it."

We sat frowning at the glass beads on the sofa table in silence. “Perhaps I shall have a glass of that wine,” he said, and helped himself. He was too gentlemanly to grimace at its sharp taste, but I noticed he set it aside after one sip and was in no hurry to take it up again.

After a frowning pause, he continued, “It almost seems the two incidents are related-certainly by time, if not by place. You were here, and privy to your uncle's doings, Miss Barron. Had he anything to do with Lady Margaret?"

"To the best of my knowledge, they never exchanged more than a nod. She did not call at Hernefield, and we do not call at Parham. Uncle lifted his hat if they chanced to meet in town or at some social do."

"And Mr. McShane never went to Tunbridge Wells?"

I hesitated a moment before answering. The situation had changed since the morning, when I had humiliated myself by giving back the necklace. It was now Lady Margaret whose actions were under a cloud. I decided to reveal Steptoe's hint.

"I am not aware of his ever going there. Our butler, however, has dropped a dark hint that he saw my uncle at Tunbridge. I cannot get anything concrete out of him. He is the slyest dog in the parish."

Lord Weylin nodded and said, “Steptoe,” in a grim voice. “Whatever possessed you to hire the man?"

"We would not have done so had you seen fit to warn us he is a thief,” I shot back. “Really, milord, I think you might have warned us."

He looked surprised at my sharp tone. “I did caution the Pakenhams, when they inquired after his character. They were in urgent need of an experienced footman, and Steptoe knows his business. They took him on probation, with a warning. He behaved himself for two years, then small items began disappearing, and they let him go. Did they not caution you, when you spoke to them?"

"We did not speak to them. As he had worked at Parham, we felt he must be reliable. We offered him the post of butler; he was happy to be promoted from footman, and accepted. As you are our neighbor, I think you might have warned us."

"Mama was concerned, but she did not feel he could do much harm here.” A look of chagrin seized his face the minute the words were out. “That is-not that I mean-"

I quenched down an angry reproof. “Hernefield is not so littered with chinoiserie as Parham, to be sure,” I snipped.

Lord Weylin wisely let the matter drop, and spoke on quickly to cover his gaffe. “How did you learn of his having taken my Tang vase? I never could prove it, and was reluctant to publicly shame the man without proof, though I am morally certain he was the culprit."

"He blurted it out himself. He thought we already knew."

"I take it, then, that you have given him his congé?"

I blushed to admit we had not. “It is this matter of his knowing something about Tunbridge Wells,” I explained. “I hope to discover what it is he knows."

"What can he know? He obviously saw your uncle there, and is trying to make gain on it."

"Yes, but…” Lord Weylin just looked patiently while I sorted out my muddled thoughts. “It is the way he says it, as though my uncle were doing something he should not."

"You are letting him play on your susceptibilities, Miss Barron. I must own that surprises me,” he said with a small smile. “You were more forthcoming at Parham. Stop a moment, and consider the facts. Mr. McShane did not have the stolen necklace; he had a worthless copy. Did he leave a large sum of money in his will? Is that what concerns you?"

"Certainly not; he did not even leave enough to bury himself. Everyone else who goes to India comes home a nabob, but Uncle only brought back five thousand pounds, and he lost that, or gave or gambled it away."

"Then it does not appear he was engaged in any criminal doings. Would you like me to have a word with Steptoe?"

"It will do no good. When I tried to quiz him, he as well as denied having said anything to me. The man is a weasel."

"You should dismiss him at once."

"I daresay you are right. Now that I know that necklace is glass, I shan't hesitate to do it."

Weylin glanced at his watch, and said, “I must be running along.” He picked up the necklace, looked a question at me, and when I did not object, he put it in his pocket.

I said, “I still think it odd my uncle had the copy."

"It is one of life's little mysteries."

"He must have obtained it at Tunbridge Wells, don't you think? If he and Lady Margaret ever had anything to do with each other, it did not happen here."

"I suggest we let sleeping dogs lie,” Weylin said, rising in a smooth motion. “There is nothing to be learned at this late date. I have business in London tomorrow, so I shall take my leave of you, Miss Barron. I shall risk boring you by repeating what I said earlier. If you learn anything more of this business, I wish you will let me know, and I shall also tell you if I chance across anything."

I murmured a vague agreement, and he left. I sat on, mulling over the matter. To Lord Weylin, with London and his politics to distract him, the affair of the necklace was a mere curiosity. For me, it loomed larger than that. I felt my uncle, and ultimately Mama, had been bilked of that missing five thousand pounds. The secret was buried at Tunbridge Wells. A trip there was well worth the effort. And to ensure smooth sailing, Weylin would be in London, well removed in case I learned something to Barry's discredit.

It was equally possible that Lady Margaret was no better than she should be, in which case I would not hesitate to inform him. The idea had not quite been put to rest that the illustrious Lady Margaret had conned my uncle into buying a fake necklace, and sold the genuine article in or around Tunbridge Wells. Would Barry have been fool enough to fall in with a bargain like that? Had Lady Margaret been younger and prettier, she might have hoodwinked him, but she was a stout matron-stylish to be sure, but with little left of her beauty. I was sorry I had let Weylin walk off with the glass beads in his pocket. They might jar someone's memory at Tunbridge Wells.

I jumped up to go after him, and noticed that he was still in the hallway, talking to Steptoe. They had their heads together like conspirators.

"Is there something amiss, Lord Weylin?” I asked, stepping toward them.

"I shall see myself out, Steptoe,” he said to the butler. Steptoe darted off.

"I was just quizzing him a little,” Lord Weylin explained. “As I suspected, he saw nothing at Tunbridge Wells. He knew my aunt used to go there, and was trying to frighten you. I fear there is nothing to be learned at Tunbridge.” He gave the sort of measured look a cat gives, just before leaping on a mouse.

"Indeed, there is no point in going all the way to Tunbridge,” I agreed. He was the last person I wanted to go there.

We exchanged good days, and he left. After he was gone, I remembered I had not gotten the necklace back from him.

Chapter Seven

Mama and I set out for Tunbridge Wells at nine the next morning, despite an early shower that promised to destroy our trip. She was not hard to convince once I had related the gist of Lord Weylin's visit, and held out the lure of recovering her brother's five thousand pounds. She was firmly convinced that Lady Margaret had taken advantage of Barry's susceptibilities.

"He was always putty in the hands of a lady,” she said, as the carriage rumbled through the mist.

"I never saw any evidence of weakness for ladies, Mama. He scarcely looked at them."

"He used to, when he was younger. A leopard does not change his spots. She fed him some tale of woe that she needed the money, and he, like a regular green-head, handed over every penny he had in the world. And to think-"

To divert the story of her paying for his coffin, I said, “Lord Weylin says no such sum appeared in Lady Margaret's bank statements. Surely Uncle Barry was not such a gudgeon."

We were back to the unanswerable question. “Where did the money go, then?” she demanded.

These thoughts had been running around in my head for hours, and when the rain let up, I put them aside and enjoyed the scenery. The carriage progressed through pretty countryside, all gleaming from the recent downpour that left the leaves dripping with crystal pendants of rain. The sun came out, striking each droplet and broadcasting tiny prisms. Borsini would have enjoyed it. He could turn his brush with equal effect to either landscape or the human form. I regretted missing my lesson.

With a longish luncheon stop to rest Mama's aching bones, our trip took seven hours. It was four in the afternoon when we entered that picturesque, hilly moorland where Sussex turns into Kent, with Tunbridge Wells nestled in its folds. We hired a room at Bishop's Down Hotel, behind the Pantiles and facing the Common. It was late in the day to begin making inquiries, but we strolled out to see something of the town before darkness descended. At Tunbridge, one goes to the promenade called the Pantiles, where all society struts to see and be seen.

The height of the season is from July to September, but already in early June there was no shortage of tourists. The serious-minded folks who came for their health were not of much interest to me, even “at my age.” An air of propriety hangs over the town, encouraged by such biblical names as the Mount Ephraim Hotel, and even Zion. Despite all this, there was a smattering of lightskirts, come to prey on the elderly gents.

We went to the Pantiles and duly admired the beauty of a colonnade on one side, a row of lime trees on the other. I had some hope of getting into the shops, but Mama felt the need of the chalybeate waters for her aching joints, so we went to the Pump Room, and paid one farthing each for a glass of impotable mineral water, which left us longing for a nice cup of tea.

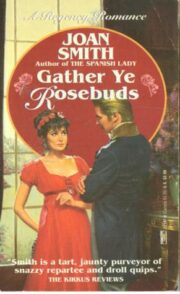

"Gather Ye Rosebuds" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Gather Ye Rosebuds". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Gather Ye Rosebuds" друзьям в соцсетях.