‘Well, if you say so, then we will have to forgive him,’ said my father, at his most charming.

Eleanor invited her to sit by her side and asked after Mrs Allen, and my father added his hopes that Mr and Mrs Allen were well.

‘They were pointed out to me as most agreeable people,’ said my father, ‘respectable in every way. We will be happy to make their acquaintance.’

Miss Morland admired my sister’s paintings, which were hanging on the wall, and was such a mixture of innocence, vitality and earnestness that I was disappointed when it was time for her to leave.

My father was equally sorry to see her go and invited her to stay and dine with us. She could not accept the invitation, having a prior engagement, but expressed herself willing to come on a future date. Arrangements were made for the day after tomorrow.

My father further surprised me by attending her to the street-door himself, saying ‘How well you walk, Miss Morland. Your grace of movement is exactly what I thought it would be when I saw you dancing. We are obliged to you for coming to see us, and we hope to see you again.’

‘Is it really the waters?’ Eleanor asked me, wondering as much as I did at my father’s unexpected good humour. ‘I did not expect them to have such a miraculous effect.’

‘I can see no other reason for it, unless he has had some good news.’

‘But what news could produce such a reaction.’

‘Perhaps Frederick is paying court to an heiress?’ I said.

‘It is always possible,’ she returned doubtfully.

‘But whatever the reason, I am glad of it, and I only hope it will continue. He has been more used to scaring your friends away than welcoming them in the past. Perhaps he has learnt from his mistakes and now sees that if you are to have company, he must put himself out to be agreeable.’

Monday 4 March

The morning was fair and Eleanor and I called for Miss Morland at the appointed time. We decided to go to Beechen Cliff, just out of town, and were soon walking alongside the river.

‘I never look at it,’ said Miss Morland, ‘without thinking of the south of France.’

I was surprised that she had been abroad, and said so. France these days is no place to visit, or at least, not for anyone who wants to return with their head on their shoulders.

‘Oh! No, I only mean what I have read about,’ she said.

I could not help smiling when she went on, ‘It always puts me in mind of the country that Emily and her father travelled through, in The Mysteries of Udolpho.’

Eleanor and I looked at each other, delighted to have found another fellow admirer of Udolpho.

Your heroine? Eleanor mouthed silently to me.

I smiled, for Miss Morland certainly had all the hallmarks of a heroine. She was sweet and innocent and honest and loving. She had a great affection for her brother. She was, for the present at least, without a mother, and under the care of her mother’s friend. And if she was not presently threatened by some cruel marquis, well, she was young and there was still time!

Mistaking my silence for disapproval, Miss Morland went on hesitantly, ‘But you never read novels, I dare say?’

‘Why not?’ I asked.

‘Because they are not clever enough for you – gentlemen read better books.’

‘The person, be it gentleman or lady, who has not pleasure in a good novel, must be intolerably stupid,’ I assured her. ‘I have read all Mrs Radcliffe’s works, and most of them with great pleasure. The Mysteries of Udolpho, when I had once begun it, I could not lay down again; I remember finishing it in two days – my hair standing on end the whole time.’

‘Yes,’ said Eleanor, ‘and I remember that you undertook to read it aloud to me, and that when I was called away for only five minutes to answer a note, instead of waiting for me, you took the volume into the Hermitage Walk, and I was obliged to stay till you had finished it.’

‘Thank you, Eleanor – a most honourable testimony. You see, Miss Morland, the injustice of your suspicions. Here was I, in my eagerness to get on, refusing to wait only five minutes for my sister, breaking the promise I had made of reading it aloud, and keeping her in suspense at a most interesting part, by running away with the volume, which, you are to observe, was her own, particularly her own. I am proud when I reflect on it, and I think it must establish me in your good opinion.’

‘I am very glad to hear it indeed, and now I shall never be ashamed of liking Udolpho myself. But I really thought before, young men despised novels amazingly,’ said Miss Morland.

I assured her I had read dozens and laughed when she called Udolpho ‘nice’. Eleanor upbraided me for my impertinence, saying to Miss Morland, ‘He is treating you exactly as he does his sister.’

And she was right. I was talking to Miss Morland with the ease that comes of friendship, instead of with the strained politeness that is usually necessary in Bath.

‘I am sure I did not mean to say anything wrong,’ said Miss Morland. ‘But it is a nice book, and why should not I call it so?’

‘Very true,’ I said with a smile, ‘and this is a very nice day, and we are taking a very nice walk, and you are two very nice young ladies. Oh! It is a very nice word indeed! It does for everything. Originally perhaps it was applied only to express neatness, propriety, delicacy, or refinement – people were nice in their dress, in their sentiments, or their choice. But now every commendation on every subject is comprised in that one word.’

‘While, in fact,’ said Eleanor, ‘it ought only to be applied to you, without any commendation at all. You are more nice than wise. Come, Miss Morland, let us leave him to meditate over our faults in the utmost propriety of diction, while we praise Udolpho in whatever terms we like best. It is a most interesting work. You are fond of that kind of reading?’

‘To say the truth, I do not much like any other.’

I laughed. There were many people who, I am sure, felt exactly as she did, but very few who had the courage to say so.

In the next half-hour I learned that she did not like history – ‘it tells me nothing that does not either vex or weary me. The quarrels of popes and kings, with wars or pestilences, in every page; the men all so good for nothing, and hardly any women at all’ – and was astonished when I admitted I was fond of it.

I discovered that she thought it was a torment for little children to learn to read – ‘if you had been as much used as myself to hear poor little children first learning their letters and then learning to spell, if you had ever seen how stupid they can be for a whole morning together, and how tired my poor mother is at the end of it, as I am in the habit of seeing almost every day of my life at home, you would allow that “to torment” and “to instruct” might sometimes be used as synonymous words’ – but she admitted that it was worth while to be tormented for two or three years of one’s life, for the sake of being able to read all the rest of it.

‘Consider, if reading had not been taught, Mrs Radcliffe would have written in vain, or perhaps might not have written at all,’ I said.

‘That indeed would have been a dreadful thing, for I have spent many happy hours with her books. It is a sad thought to even contemplate that she might never have written them. I begin to think as you do, that learning to read and write is no bad thing, after all. Her books are so very entertaining. And instructive, too. I am sure I know a great deal about Europe through reading her books; about France and the Alps and Italy. Why, without them I would know nothing of Venice at all. Do they really have gondolas to ride in?’ she asked.

‘Yes, they really do.’

‘And is the city really full of canals?’

‘Yes, it is.’

‘Then I think that Udolpho is as good as a history book, and as instructive as any other, for though it does not contain as many facts, those facts it does contain are eagerly sought after and easily absorbed.’

‘As good an argument for the studying of Mrs Radcliffe at Oxford as I have ever heard.’

We walked on, admiring the river and the line of the cliff.

As Eleanor and I discussed its suitability for a sketch, it was easy to see that Miss Morland had not had the benefit of a drawing master and I was happy to instruct her. I soon learnt that she had great natural taste, for when I pointed out the desirability of a drawing having the river in the foreground, with the rolling hills in the distance and a beech tree in the middle distance for perspective, she agreed with everything I said.

Talk of the oak led us to forests, forests to enclosures, enclosures to waste land, and from there it was a short step to politics, which is a subject likely to end any conversation. And so it was with this one.

After a while, Miss Morland recovered from politics and returned to her favourite theme, saying, ‘I have heard that something very shocking indeed will soon come out in London. It is to be uncommonly dreadful. I shall expect murder and everything of the kind.’

Eleanor was alarmed, and Miss Morland was puzzled, and I laughed at them both.

‘You talked of expected horrors in London,’ I said, ‘and instead of instantly conceiving, as any rational creature would have done, that such words could relate only to a circulating library, my sister immediately pictured to herself a mob of three thousand men assembling in St. George’s fields, the Bank attacked, the Tower threatened, the streets of London flowing with blood, a detachment of the Twelfth Light Dragoons (the hopes of the nation) called up from Northampton to quell the insurgents, and the gallant Captain Frederick Tilney, in the moment of charging at the head of his troop, knocked off his horse by a brickbat from an upper window. Forgive her stupidity. The fears of the sister have added to the weakness of the woman; but she is by no means a simpleton in general.’

Eleanor laughed but Miss Morland, unsure whether I were serious or not, looked grave.

‘And now, Henry, that you have made us understand each other, you may as well make Miss Morland understand yourself, unless you mean to have her think you intolerably rude to your sister, and a great brute in your opinion of women in general. Miss Morland is not used to your odd ways,’ Eleanor said.

I smiled at Miss Morland’s expression as understanding dawned, for she was no doubt realizing that Eleanor and I teased each other in the way that she and her brothers and sisters did.

‘I shall be most happy to make her better acquainted with them,’ I said.

My eyes lingered on her face. It really was remarkably pretty, surrounded by soft hair, and I thought that Miss Morland herself would be a fitting subject for a drawing.

‘No doubt; but that is no explanation of the present,’ said Eleanor.

‘What am I to do?’ I asked.

‘You know what you ought to do. Clear your character handsomely before her. Tell her that you think very highly of the understanding of women.’

‘Miss Morland, I think very highly of the understanding of all the women in the world, especially of those – whoever they may be – with whom I happen to be in company.’

‘That is not enough. Be more serious.’

‘Miss Morland, no one can think more highly of the understanding of women than I do. In my opinion, nature has given them so much that they never find it necessary to use more than half.’

Miss Morland looked perplexed, and I thought how well it became her.

‘We shall get nothing more serious from him now, Miss Morland,’ said Eleanor. ‘He is not in a sober mood. But I do assure you that he must be entirely misunderstood, if he can ever appear to say an unjust thing of any woman at all, or an unkind one of me.’

Miss Morland smiled at me. I offered her my arm and as she took it I felt a surprising pleasure at her touch, and we continued with our walk.

Eleanor was not eager to lose Miss Morland’s company, and neither was I. We accompanied her into the house in Pulteney Street where she was residing, and paid our respects to the Allens and then we parted, well pleased with each other.

‘It seems you have found an agreeable friend,’ I said to Eleanor. ‘And, moreover, one my father is disposed to like.’

‘And who would not like her? She is pretty, original, and becomingly ignorant,’ said Eleanor.

I looked at her in surprise.

‘Confess it! You loved instructing her,’ said Eleanor.

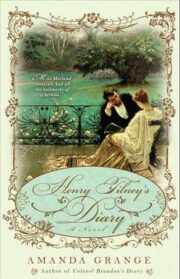

"Henry Tilney’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Henry Tilney’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Henry Tilney’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.