"We've got to find her, Daddy, and bring her home."

"Find her," he said angrily. "Those people close around their own like clams. They won't talk to us; they won't tell us anything."

He reached for his nearly empty bottle of bourbon and poured himself another drink. "Maybe she'll come to her senses and call us or come home," he muttered.

"Daddy, we've got to call the police. She's not in her right mind after all this sadness and tragedy. They'll understand and they'll help us," I said.

He shook his head. "Waste of time."

"No, it isn't," I insisted. "I can't stand the thought of her under the influence of these people. If you don't call them, I will."

"What are you going to tell them? That your mother wandered off to practice voodoo rituals someplace?" he asked disdainfully.

"Yes."

"They won't take you seriously, Pearl. They have a great many more urgent problems to deal with in this city."

"It's worth a try, Daddy."

He took a long gulp of bourbon.

"Daddy! You can't just sit there all day and night and drink yourself to sleep," I cried.

"She's gone, run off, returned to her bizarre past, and my son is dead," he said. "My little boy is gone. My other little boy is catatonic. What did I do to deserve this?"

"Stop this self-pity, Daddy. Mommy needs us."

He lowered his chin to his chest. I felt heat crawling up my spine. What had happened to Daddy and Mommy was terrible. No parent should endure such tragedy, but if Daddy didn't find a well of strength from which to draw new energy and determination, more terrible things loomed over us. Mommy had asked me to be strong. If that meant being cruel first, so be it, I thought.

"Is this the way you handle all your crises, Daddy? You wallow in them?" I sneered. "Is this why you ran off to Europe when Mommy was pregnant with me?" He looked up sharply, knitting his brows as if a sharp pain had cut across his forehead, as if my words were tiny knives.

"No, I—"

"You left her alone to face the anger and the abuse. She gathered strength and returned to the bayou, and she managed to care for herself and for me while you were enjoying the most expensive restaurants and the wildest parties in Europe. Now, when she needs you again, you sit there gulping whiskey and moaning about what's happened to you."

"Pearl, please, that's not the way I was or the way I am," he argued.

"Then get a hold of yourself and let's go find her. Call the police," I demanded sharply, firing my words like bullets.

He nodded, sobering up quickly. "All right," he said. "Maybe you're right. We'll start with the police."

I straightened my shoulders and wiped away my tears with the back of my hand. "I'll look in on Pierre. We've got to find Mommy and bring her home for his sake most of all," I added. Daddy bit down on his lower lip and nodded. Pivoting on my heel, I marched out of the room and up the stairs quickly, so he wouldn't see how painful it was for me to treat him so harshly. I had to pause at the landing to catch my breath and slow my thumping heart.

Mrs. Hockingheimer was dozing in her chair in Pierre's room when I looked in on him. She heard me and looked up quickly.

"How is he doing?" I asked softly. His face was in repose, but his lips were crooked, reacting to some nightmare, no doubt, I thought.

"He's having a restless sleep," she said. "I couldn't get him to eat any more, but he did drink some water. He felt a little warm, but he has no fever."

"Okay," I said sadly.

"Mademoiselle," she called as I started to turn from the doorway. "He did mutter something."

"What?"

"He's calling for his mother," she said. "Where is your mother, if I may ask?"

Mrs. Hockingheimer wasn't being nosy. Anyone would have wondered why Pierre's mother wasn't at his side, I thought. "My mother is very troubled by what happened, the whole tragedy. She believes herself responsible, and she's disappeared. We've got to call the police and . . ." My lips started to quiver badly. It was as if my face had mutinied. I couldn't pronounce the words. They got choked up in my throat.

Mrs. Hockingheimer saw what was happening and rose quickly to come to me. "You poor dear. I didn't mean to upset you," she said and embraced me.

"No one has seen her. My father and I are at our wit's end. We're calling the police right now."

"I'm so sorry. There, there," she said, patting my hand. "You must remain strong. Don't worry about Pierre. I will watch him very closely."

"Thank you, Mrs. Hockingheimer." I took a deep breath.

Mrs. Hockingheimer dabbed away the tears that lingered on my cheeks and smiled. "You're a strong young woman. You'll find a way to help your mother," she assured me.

I thanked her again and went downstairs to be with Daddy when the police arrived.

A detective and two uniformed patrolmen came to our door. The detective introduced himself as Lieutenant Ribocheaux. He was about as tall as Daddy, but with much wider shoulders and a square jaw. He looked like an ex–football player. The patrolmen stood in the doorway of Daddy's study and listened with Lieutenant Ribocheaux as Daddy described the terrible events that had unfolded. Daddy showed him Mommy's letter, and I then told him about Mommy's visiting the cemetery. I hadn't spelled out the details before. Daddy's eyes went as wide and round as quarters when he heard me talk of the screeching, the black cat, Mommy's walking about with a candle, and the whispering.

"This young woman who came to your door with the letter," Lieutenant Ribocheaux asked me, "had you seen her before? Was she at the cemetery too or at this house where your mother went to see the dead lady?"

"No, sir."

"And when you ran after her, you say she threw a snake's head out of the streetcar window?"

"Yes. I dropped it. It's probably still there. I can show it to you."

"I imagine it's only one of those souvenirs that the tourists buy in the voodoo shops in the French Quarter," he said.

"Still, I couldn't bring it home."

"I understand," he said, smiling. He turned to the uniformed policemen. "Ted, you and Billy take a look. Maybe it's still there, and it might give us some clue," he said, but from the looks on their faces, I knew they were doing it only to placate me. I told them where it would be, and they left.

Lieutenant Ribocheaux turned back to Daddy. "Monsieur Andreas, was your wife under a doctor's care?"

"Not in the sense I believe you mean," Daddy replied, "but our physician had given her sedatives."

Lieutenant Ribocheaux took out his notepad. "You've called all her friends, people she might go see, I imagine?"

"Everyone we could think of," Daddy said. "No one has heard from her or seen her."

"Relatives?"

"We have none presently in New Orleans. My parents are in Europe for the summer."

"Well, where are your closest relatives?"

"My wife's family comes from the bayou, around Houma, but she wouldn't go to them," Daddy added. "We don't get along that well."

"Except with Aunt Jeanne," I reminded him. "Yes, but I don't think she would have gone to Jeanne," Daddy said.

"Okay," Lieutenant Ribocheaux said. "Let me have the address of that house, the Jackson residence." I gave it to him, and he jotted it down quickly. "We'll pay them a visit," he promised. "In the meantime give us a recent picture of Madame Andreas, please. I'd like to speak with the butler, too, and get a description of what she was wearing when she was last seen here."

Daddy turned to me, and I went to fetch Aubrey. He was reluctant to tell the police any of the bizarre details about Mommy's behavior, but I urged him to be as forthcoming as possible. Lieutenant Ribocheaux took more notes.

The patrolmen returned. They had found the snake's head, but Lieutenant Ribocheaux said there was nothing remarkable about it. "As I suspected, it's no different from what you can buy at Marie Laveau's. Someone's having some fun with you," he added.

"If that's true, it's very cruel," I replied.

After the police left, I sat with Daddy in his study.

"I'm not optimistic about their finding her, Pearl. They'll send a patrol car around, all right, but unless Mommy is standing right in front of them . . . I know these voodoo people. They believe they are doing something spiritual and something good. They won't want Mommy to be found and brought back. That might break some sort of spell."

"Maybe we should go to Nina's sister's house too, Daddy," I suggested, "and stay until she tells us the truth."

"We won't fare any better. At least the police carry some authority. Why don't you go up to bed, honey? No sense in both of us staying up and worrying all night. Besides, I need you strong and healthy for the days to come."

"You're not going to remain down here all night, are you, Daddy?" I gazed at the bottle of bourbon.

Daddy saw where my eyes were fixed. "I won't drink anymore," he promised. "I've got to stay alert in case we're needed."

I nodded, rose, and went to him. We hugged, and he held on to me for a few moments longer than usual before releasing me and sitting back.

"Good night, Daddy."

"Good night, princess. Thanks for making me come to my senses," he said, smiling. "For a moment there I thought I was looking at your mother when she was about your age."

I kissed him again and walked away. At the doorway I turned. He had already swung his chair around and was gazing up at his and Mommy's portrait again, wondering, I'm sure, how they would ever get back to the happy, wonderful time they had when the portrait was painted.

When I peeked in on Pierre, both he and Mrs. Hockingheimer were fast asleep, so I closed the door softly and went to my room. Just as I got into bed, Sophie called. I told her all that had happened, right up to the black girl throwing the snake's head out of the streetcar window.

"I don't know much about voodoo," she said, "but nana does. I could ask her if you want."

I thought about it. I was beginning to agree with Daddy. The more we involved ourselves with these things, the more twisted and confused we became. All it did was fill my head with bad thoughts and give me nightmares. "No, thanks. I'd rather not know."

"I can come over after work and help you go looking, if you want," she volunteered.

"Thank you, but I wouldn't even know where to start. We'll wait and see what the police say tomorrow."

"Maybe she'll come home tonight."

"Maybe."

"I'll say a prayer for you and your family," she said. How ironic, I thought. A few weeks ago Sophie had sat in the streetcar gazing out the window at the Garden District, her face full of envy as I waved good-bye and started for home. She would have given anything to trade places with me, I'm sure. Now I was the object of her pity and sympathy. Money makes people comfortable, but it doesn't guarantee happiness, I thought.

"Thank you, Sophie." It brought tears to my eyes to think that none of my so-called upper-class friends from school had called or visited, but my new friend, my poorest friend, cared enough to volunteer her time to help me.

After I hung up, I put my palms together under my chin, closed my eyes, and said my own prayer. I prayed for Mommy, I prayed for Pierre, I prayed for Daddy, and I prayed that I would have the strength to help everyone. Then I tried to fall asleep. I tossed and turned for hours before drifting off, but my sleep was restless and continually interrupted. I woke often with a start, listening hard for the sound of a door being opened or a phone ringing. I longed to hear Mommy's voice echoing through the hallway or up the stairs, but the dead silence of our morgue-like house was all I heard.

Daddy was disheveled and tattered-looking in the morning. No doubt he had stayed awake most of the night. He had slept on the sofa in his study when he did catch some sleep. I made sure he ate something substantial for breakfast and then persuaded him to take a shower. Mrs. Hockingheimer had Pierre up and washed. She got him to eat a portion of his breakfast, but he had the same empty look in his eyes, the same anticipation when I entered. I spoke to him for a while. His lips quivered and then formed the word "Mommy." It shattered the thin veneer on my heart and made me gulp back the tears.

I convinced Daddy that he should call Lieutenant Ribocheaux to see if they had any leads, but they didn't. Daddy hung up the phone and looked at me, his face lined with exhaustion and frustration.

"I told you it wouldn't do us any good to call the police," he said. "They don't take this voodoo thing seriously, and when an adult disappears, they're not really concerned. Of course, they promised to keep looking."

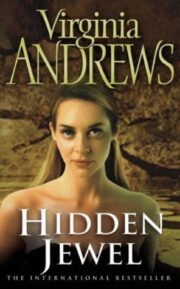

"Hidden Jewel" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Hidden Jewel". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Hidden Jewel" друзьям в соцсетях.