"I'm afraid you'll have to have breakfast with your brothers only this morning," Daddy said. "I've al-ready eaten, and so has your mother, and we're busier than two bees in a hive."

"I wish you and Mommy hadn't planned quite such a large affair for me, Daddy."

"What? I wouldn't have it any other way. In fact, it's not big enough. Every hour I remember someone else we should have invited."

"The guest list is already a mile long!"

He laughed."Well, with my business interests and your mother's art crowd, not to mention your teachers and friends, we're lucky it's only a mile."

"And my portrait will be unveiled in front of all those people. I'll be so embarrassed."

"Don't think of it as your portrait, Pearl. Think of it as your mother's art," he advised. I nodded. Daddy was always so sensible. He would surely have made a wonderful doctor.

"I'll eat quickly and help you, Daddy." "Nonsense. You relax, young lady. You have a big night ahead of you. You won't know how big until it starts. And you have your speech to worry over, too."

"Will you listen to me practice later?"

"Of course, princess. We'll all be your first audience. But right now I've got to see about our parking arrangements. I've hired a valet service."

"Really?"

"We can't have our guests riding around looking for a place to park, can we? Make sure your brothers eat their breakfast and don't annoy anyone, will you?" he asked and kissed me again before hurrying to the front of the house.

Jean and Pierre were at the table, both looking so polite and innocent that I knew they were up to something. Strands of Jean's blond hair hung down over his forehead and eyes. As usual his shirt was buttoned incorrectly. Pierre's appearance was perfect, but Pierre wore that tiny smirk around his lips and Jean looked at me with his blue eyes twinkling. I checked my seat to be sure they hadn't put honey on it so I would stick to it.

"Good morning, Pearl," Pierre said. "How's it feel to be graduating?"

"I'm very nervous," I said and sat down. They both stared. "Did you two do anything silly?"

They shook their heads simultaneously, but I didn't trust them. I scrutinized the table, checked the floor by my chair, and studied the salt and pepper shakers. Once, they put pepper in the salt shaker and salt in the pepper, and another time, they put sugar in the salt shaker.

They dipped their spoons into their cereal and ate with their eyes still fixed on me. I looked up at the ceiling to be sure there wasn't a fake black widow spider dangling above me.

"What have you two done?" I demanded.

"Nothing," Jean said too quickly.

"I swear if you do anything today, I'll have the two of you locked in the basement."

"I can get out of a locked room," Jean bragged. "I know how to pick a lock. Right, Pierre?"

"It's not hard to do, especially with our old locks," Pierre said pedantically. He had a way of making his eyes small and pressing his lower lip over his upper whenever he offered a serious opinion.

"I can take the hinges off the door, too," Jean claimed.

"All right. Stop talking about it. I'm not serious," I said. Jean looked disappointed.

"Good morning, mademoiselle," our butler, Aubrey, said as he came in from the kitchen with a glass of fresh orange juice for me. Aubrey had been with us for years and years. He was the proper Englishman at all times. He was bald with small patches of gray hair just over his ears. His thick-rimmed glasses were always falling down the bridge of his bony nose, and he would squint at us with his hazel eyes.

"Morning, Aubrey. I'll just have some coffee and a croissant with jam this morning. My stomach is full of butterflies."

"Ugh," Jean said. "They were caterpillars first,"

"She just means she's nervous," Pierre explained.

"Because you got to make a speech?" Jean asked.

"Yes, that mostly," I said.

"What's it about?" Pierre asked.

"It's about how we should be grateful for what we have, for what our parents and teachers have done for us, and how that gratitude must be turned into hard work so we don't waste opportunities and talents," I explained.

"Boring," Jean said.

"No, it's not," Pierre corrected him.

"I don't like sitting and listening to speeches. I bet someone throws a spitball at you," Jean threatened.

"It better not be you, Jean Andreas. There's plenty that has to be done around here all day. Don't get underfoot and don't aggravate Mommy and Daddy," I warned.

"We can stay up until everyone leaves tonight," Pierre declared.

"And Mommy let us invite some of our friends," Jean added. "We should light firecrackers to celebrate."

"Don't you dare," I said. "Pierre?"

"He doesn't have any."

"Charlie Littlefield does!"

"Jean!"

"I won't let him," Pierre promised. He gave Jean a look of chastisement, and Jean shrugged. His shoulders had rounded and thickened this past year. He was tough and sinewy and had gotten into a half dozen fights at school, but I learned that three of those fights were fought to protect Pierre from other boys who teased him about his poetry. All their friends knew that when someone picked a fight with Pierre, he was picking a fight with Jean, and if someone made fun of Jean, he was making fun of Pierre as well.

Mommy and Daddy had to go to school to meet with the principal because of Jean's fights, but I saw how proud Daddy was that Jean and Pierre protected each other. Mommy bawled him out for not bawling them out enough.

"It's a tough, hard world out there," Daddy said. "They've got to be tough and hard too."

"Alligators are tough and hard, but people make shoes and pocketbooks out of them," Mommy retorted. No matter what the argument or discussion, Mommy had a way of reaching back into her Cajun past to draw up an analogy to make her point.

After breakfast I returned to my room to fine-tune my valedictory address, and Catherine called.

"Have you decided about tonight?" she asked.

"It's going to be so hard leaving my party. My parents are doing so much for me," I moaned.

"After a while they won't even know you're gone," Catherine promised. "You know how adults are when make parties for their children; they're really making them for themselves and their friends."

"That's not true about my parents," I said.

"You've got to go to Lester's," she whined. "We've been planning this for months, Pearl! Claude expects it. I know how much he's looking forward to it. He told Lester, and Lester told me just so I would tell you."

"I'll go to the party, but I don't know about staying overnight," I said.

"Your parents expect you to stay out all night. It's like Mardi Gras. Don't be a stick-in-the-mud tonight of all nights, Pearl," she warned. "I know what you're worried about," she added. Catherine was the only other person in the world who knew the truth about Claude and me.

"I can't help it," I whispered.

"I don't know what you're so worried about. You know how many times I've done it, and I'm still alive, aren't I?" Catherine said, laughing.

"Catherine . . ."

"It's your night to howl. You deserve it," she said. "We'll have a great time. I promised Lester I would see that you were there."

"We'll see," I said, still noncommittal.

"I swear, Pearl Andreas, you're going to be dragged kicking and screaming into womanhood." She laughed again.

Was this really what made you a woman? I wondered. I knew many of my girlfriends at school felt that way. Some wore their sexual experiences like badges of honor. They had a strut about them, a demeanor of superiority. It was as if they had been to the moon and back and knew so much more about life than the rest of us. Promiscuity had given them a sophistication and filled their eyes with insights about life, and especially about men. Catherine believed this about herself and was often condescending.

"You're book-smart," she always told me, "but not life-smart. Not yet."

Was she right?

Would this be my graduation night in more ways than one?

It was difficult to return to my speech after Catherine and I ended our conversation, but I did. After lunch, Daddy, Mommy, and the twins sat in Daddy's office to listen to me practice my delivery. Jean and Pierre sat on the floor in front of the settee. Jean fidgeted, but Pierre stared up at me and listened intently.

When I was finished, they all clapped. Daddy beamed, and Mommy looked so happy, I nearly burst into tears myself. Graduation was set to begin at four, so I went upstairs to finish doing my hair. Mommy came up and sat with me.

"I'm so nervous, Mommy," I told her. My heart was already thumping.

"You'll do fine, honey."

"It's one thing to deliver my speech to you and Daddy and the twins, but an audience of hundreds! I'm afraid I'll just freeze up."

"Just before you start, look for me," she said. "You won't freeze up. I'll give you Grandmère Catherine's look," she promised.

"I wish I had known Grandmère Catherine," I said with a sigh.

"I wish you had too," she said, and when I gazed at her reflection in the mirror, I saw the deep, far-off look in her eyes.

"Mommy, you said you would tell me things today, things about the past."

She nodded and pulled back her shoulders as if she were getting ready to sit down in the dentist's chair.

"What is it you want to know, Pearl?"

"You never really explained why you married your half brother, Paul," I said quickly and lowered my eyes. Very few people knew that Paul Tate was Mommy's half brother.

"Yes, I did. I told you that you and I were alone, living in the bayou, and Paul wanted to protect and take care of us. He built Cypress Woods just for me."

I remembered very little about Cypress Woods. We had never been back since Paul's death and the nasty trial for custody over me that had followed.

"He loved you more than a brother loves a sister?" I asked timidly. Just contemplating them together seemed sinful.

"Yes, and that was the tragedy we couldn't escape."

"But why did you marry him if you were in love with Daddy and I had been born?"

"Everyone thought you were Paul's daughter," she said. She smiled. "In fact, some of Grandmère Catherine's friends were angry that he hadn't married me yet. I suppose I let them believe it just so they wouldn't think I was terrible."

"Because you had gotten pregnant with Daddy and returned to the bayou?"

"Yes."

"Why didn't you just stay in New Orleans?"

"My father had died, and life with Daphne and Gisselle was quite unpleasant. When Beau was sent to Europe, I ran off. Actually," she said, "Daphne wanted me to have an abortion."

"She did?"

"You wouldn't have been born."

I held my breath just thinking about it.

"So I returned to the bayou where Paul took care of us. He even helped me give birth to you. When I heard Daddy was engaged to someone in Europe, I finally gave in and married Paul."

"But Daddy wasn't engaged?"

"It was one of those arranged things. He broke up with the young lady and returned to New Orleans. My sister had been seeing him. She had a way of getting whatever she wanted, and your father was just another trophy she wanted," Mommy said, not without a touch of bitterness in her voice.

"Daddy married Gisselle because she looked so much like you, right?" It was something I had squeezed out of Daddy when he had decided to stem the flood of questions I poured at him.

"Yes," Mommy said.

"But neither of you were happy?"

"No, although Paul did so much for us. I devoted all my time to my art and to you. But then, when Gisselle became sick and comatose . . ."

"You took her place." I knew that story. "And then?"

"She died, and there was the terrible trial after Paul's tragic death in the swamp. Gladys Tate wanted vengeance. But you knew most of that, Pearl."

"Yes, but, Mommy . . ."

"What, honey?"

I lifted my eyes to gaze at her loving face. "Why did you get pregnant if you weren't married to Daddy?" I asked. Mommy was so wise now; how could she not have been wise enough to know what would happen back then? I had to ask her even though it was a very personal question. I knew most of my girlfriends, including Catherine, could never have such an intimate conversation with their mothers.

"We were so much in love we didn't think. But that's not an excuse," she added quickly.

"Is that what happens, why some women get pregnant without being married? They're too much in love to care?"

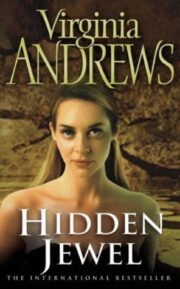

"Hidden Jewel" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Hidden Jewel". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Hidden Jewel" друзьям в соцсетях.