‘I am sure of that.’

‘And I should not wish to bother my lord Duke, and even if he felt so disposed I might discourage him.’

‘How unkind!’

She laughed aloud. ‘Very glib. And I have no more desire to marry you than you have to marry me. So set yourself at ease on that score.’

‘Marriage?’ gasped the Duke.

‘Let us be honest. Whenever the son of a king visits a princess the intention is always there. Your visit, sir, is in the nature of an inspection. I am not asking you to deny this. I am only putting your mind at rest.’

She whipped up her horse and rode on; the Duke stared after her. What a strange creature! What did she mean? Was she coquettish? Was she chiding him for not making advances or warning him off lest he did? He attempted to follow her; then he saw her making for a tall soldier on horseback.

She joined him; she threw a glance over her shoulder at the Duke. Nothing could have told him more clearly that she had no wish for him to join them.

The Duke fell back and rode with the rest of the party.

Life was conducted in a very strange manner at the Court of Brunswick, he thought, and the strangest part of it was the behaviour of the Princess Caroline.

A messenger arrived from England with letters and a package for the Duke of York and to his astonishment, when he opened the packet, he found a necklace and earrings set with splendid diamonds.

The Duke read the letter which accompanied them and which was signed by his father.

The King thought that the Duke of York might wish to make a present to his cousin Caroline and for this purpose he had sent him the diamonds.

The Duke looked at them speculatively for some minutes.

He took out the necklace and examined the stones. To give them to Caroline would be tantamount to making her an offer of marriage. So that was clearly what the old man had in mind. It was quite out of the question. He had no desire to marry her. Moreover, he might well be refused and that would not please the King. Would she be allowed to refuse an offer from England? She had hinted in one or two of the conversations that her father had told her she should never be forced into marriage.

He shook his head, put the necklace back into its case and carefully rewrapped the package.

He sat down and thought of returning home and the kind of woman to whom he would present the necklace. He fancied she would be rather like Mrs.

Robinson; and she would be English.

The Duke of York had left the Court of Brunswick. Many shook their heads.

Was Caroline going to reject all her hopes of marriage? What a strange girl she was! It seemed very likely that she would never marry at all.

Caroline knew they whispered of her. ‘Let him go,’ she said to the Baroness de Bode. ‘He’s a pleasant enough young man but not for me.’

The Baroness said: ‘He is the son of the King of England.’

Caroline pouted. ‘The second son.’

‘Good Heavens, is Your Highness hoping for the Prince of Wales?’

Caroline turned away with a laugh. Let them think so. Let them imagine her to be ambitious. She was ambitious— for a home with the man she loved and a large family of happy children.

And she was in love.

Under cover of dusk she slipped out to meet her Major. He was a little alarmed— for her, of course. He had declared frequently that he did not care what happened to him.

‘Silly man,’ she cried fondly. ‘My father understands me. He knows he could never force me into marriage. He will let me marry where I will.’

Then if this was so why not disclose their plans to the Duke? That was what Caroline thought; but Major von Töbingen begged her to keep their secret a little longer.

She gave way. But, she warned him, not for long. He was there waiting in the shadows— tall, mysterious in his long cloak.

She threw herself into his arms and hugged him in the unrestrained manner which while it delighted him alarmed him too.

‘I have a present for you, my dearest,’ she said. ‘It’s a token.’

She gave him the large amethyst pin which she had had made for him from one of her rings.

‘I shall expect you to wear it— always,’ she told him.

She began to talk rapidly of the future. She would speak to her father and they would be married.

‘It will never be,’ he told her in despair. ‘They will never allow a princess to marry a mere soldier!’

‘A mere soldier! You— a mere soldier! There is nothing mere about you. I love you, do you hear. I love you. That means that my father will give his consent.’

He whispered that they must speak quietly or they would be overheard.

‘Let them hear!’ Her voice rang out. ‘What does it matter? I want the whole Court to know. Why should they not? I have made up my mind.’

She was exuberant and impatient. Marriage with her Major would be perfect bliss, she told him.

‘Children— do you want children? But of course you do. Dear little children.

All our own. Every time, I go to the village to see my adopted ones I say to myself: They are lovely. I adore them. But soon I shall have little ones of my own. I cannot wait. Why should I? I am no longer a child. I must speak to my father— I must— I must— I will! ‘

But he begged her to wait a little longer and because she loved him she agreed.

Major von Töbingen was seen to wear a big amethyst pin. Sometimes his fingers would stray to it and linger there lovingly. The Princess Caroline constantly contrived to be where he was; and her eyes were seen to rest on the pin. It was her gift to him, was the general comment.

It was impossible not to be aware of the Princess’s emotions. She had never been one to hide them at any time; and Caroline in love was at her most emotional row like the Princess to reject the Princes of Orange and Prussia and to show the Duke of York quite clearly that she had no wish to marry him— and then to fall besottedly in love with a major in the Army.

The rumours grew fast. She was already with child, it was whispered. Well, it wouldn’t be the first time. That other occasion was recalled when during a ball an accoucheur had to be called to the palace.

A fresh scandal was about to break.

Madame de Hertzfeldt consulted with the Duke and as a result one day not very long after she had presented him with the amethyst pin, Caroline went to their usual trysting place where she waited in vain for her Major.

He had gone, and when she had demanded of his fellow officers where he was they could not tell her. He had been there one morning and by afternoon had disappeared. There was simply no trace of him.

She had stamped her foot; she had raged. ‘Where? Where? Where?’ she had cried But they could not help her.

One of them suggested that her father the Duke might be able to explain.

She went to her father’s apartments, Madame de Hertzfeldt was with him, and they were expecting her.

‘My dear child—’ began her father and would have put his arms about her but she cried out― ‘Where is Major von Töbingen?’

‘Major von Töbingen’s duties have taken him away,’ said the Duke gently, ‘What duties? Where?’

The Duke looked surprised. Even his dear daughter could not speak to him in that manner.

‘Suffice it that he is no longer with us.’

‘No longer with us! I tell you I shall not be satisfied with that. I want to know where he is. I want him brought back. I am going to marry him. Nothing— nothing— nothing— is going to stop me.’

The Duke looked at Madame de Hertzfeldt who said gently: ‘Caroline, you must realize that a princess cannot marry without the approval of her family.’

‘I know nothing of other princesses. I only know what I myself will do. I will marry Major von Töbingen.’

The Duke said: ‘No, my dear, you will not.’

She turned on him. ‘You said that I should not be forced to marry against my will.’

‘I did; and you shall not be. But I did not give you permission to marry without my consent.’

‘So you have sent him away.’

‘Caroline,’ said Madame de Hertzfeldt, ‘it was the only thing we could do.’

‘The only thing you could do. And who are you, Madam, to govern me? Be silent! If I have to listen to my father, I will not to you. I shall not stay here.’ She began to pace the room.

She was like a tigress, thought Madame de Hertzfeldt. How peaceful we should be if she would marry and go away from the Court! The Duke was about to protest when Madame de Hertzfeldt signed to him not to do so on her account. She was sure that they must try to reason with Caroline gently. She was always afraid on occasions like this that Caroline’s delicately- poised mind would over-balance and she knew what great grief this would bring to the Duke.

The Duke said: ‘You must have realized the unsuitability of such a match.’

‘It is suitable because we love each other. What more suitable? Would you have me make a marriage such as yours? Would you give me a mate whom I must despise as you do yours?’

The Duke clenched his hands. She was shouting and he knew that her words would be overheard.

‘Don’t try to silence me. You have taken my lover from me. He is good and kind and handsome but that would not do. You would marry me to some ill- formed monstrosity just because he is a royal. That would be suitable— suitable — suitable―’

Madame de Hertzfeldt had slipped out of the room. The Duke guessed that it was to take some action. In the meantime he tried to quiet his daughter.

‘Caroline, I will not have you shout in this manner. I will have you remember your place here. If I cared, I could arrange a marriage for you entirely of my choosing. Do not imagine that because I have so far been lenient with you, I shall continue to be so. So much depends on your own conduct.’

That quieted her. It was true she was a little afraid of him. She did realize that she owed her free way of life to him‚ that she was not treated as so many princesses in her position would have been.

‘Papa,’ she said, ‘I love him!’

‘I know, my dear, but it could not be. You must realize that.’

‘Why not? It seems so senseless! Why should we have to be made unhappy when we could be happy, when we could have healthy children and bring them up in a happy home.’

‘It is the penalty of royalty.’

‘But we ourselves make those penalties! Why? Why? Why cannot we be free?

Why do we pen ourselves in with our misery merely to preserve our silly royalty?’

‘Pray do not speak in that way, daughter.’

‘So I may not even speak as I will!’ Her eyes flashed with sudden rage. ‘I will not endure this treatment, I tell you. I will make my own life I will go and find him— I will renounce your precious royalty for the sake of love.’

Madame de Hertzfeldt had returned; she was carrying a cup. ‘Caroline,’ she said, ‘you know you have my sympathy. Pray, do as I say.’

‘What is that?’

‘Drink this. It will help you to sleep for a while. You are distraught; and when you have recovered a little from this shock you may talk with your father.’

For a moment it seemed as though Caroline would dash the cup out of Madame de Hertzfeldt’s hand; then that tactful woman said, ‘You will feel calmer. You may be able to convert him to your ideas— or even accept his.’

The hopelessness of her situation was brought home to Caroline. The walls of the apartment seemed to close in upon her. Shut in, she thought, imprisoned in royalty.

The Princess Caroline was ill. She would eat nothing; she could not sleep. She lay hollow-eyed in her bed.

She had received a letter from Major von Töbingen in which he said goodbye to her. He begged her to accept their separation which in his heart he had known was inevitable from the beginning. She must not try to find him, for even if she did— which was not possible— he could not marry her. To do so would be an act of treason, she must realize that. He would never forget her. He would love her until he died if she would occasionally think of him with tenderness that was all he would ask of life.

She wept bitterly over the letter and kept it under her pillow to read again and again The dream of love and marriage with the man of her, choice was over. She was listless‚ and they feared for her life.

It gave her a savage pleasure to see their concern. Her father came to her room each day, he was very tender. If there was anything she wished for— except that one thing which was all she wanted— she might have it.

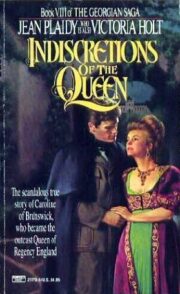

"Indiscretions of the Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Indiscretions of the Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Indiscretions of the Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.