"I didn't bargain for this," she said fiercely. "I could face the brutality of my uncle, and the pathetic dumb stupidity of Aunt Patience; even the silence and the horror of Jamaica Inn itself could be borne without shrinking and running away. I don't mind being lonely. There's a certain grim satisfaction in this struggle with my uncle that emboldens me at times and I feel I'll have the better of him in the long run, whatever he says or does. I'd planned to take my aunt away from him and see justice done, and then, when it was all over, to find work on a farm somewhere and live a man's life, like I used to do. But now I can't look ahead any more; I can't make plans or think for myself; I go round and round in a trap, all because of a man I despise, who has nothing to do with my brain or my understanding. I don't want to love like a woman or feel like a woman, Mr. Davey; there's pain that way, and suffering, and misery that can last a lifetime. I didn't bargain for this; I don't want it."

She leant back, her face against the side of the carriage worn out by her torrent of words and already ashamed of her outburst. She did not care what he thought of her now. He was a priest, and therefore detached from her little world of storm and passion. He could have no knowledge of these things. She felt sullen and unhappy.

"How old are you?" he asked abruptly.

"Twenty-three," she told him.

She heard him swallow in the darkness, and, taking his hand away from hers, he placed it once more upon the ebony stick and sat in silence.

The carriage had climbed away from the Launceston valley and the shelter of the hedges and was now upon the high ground leading to the open moorland, exposed to the full force of the wind and the rain. The wind was continuous, but the showers were intermittent, and now and again a wild star straggled furtively behind a low-sweeping cloud and hung for an instant like a pinprick of light. Then it would go, obscured and swept away by a black curtain of rain, and from the narrow window of the carriage nothing could be seen but the square dark patch of sky.

In the valley the rain had fallen with greater steadiness, and the wind, though persistent, had been moderate in strength and checked in its passage by the trees and the contour of the hill. Here on the high ground there was no such natural shelter; there was nothing but the moor on either side of the road, and, above, the great black vault of the sky; and there was a scream in the wind that had not been before.

Mary shivered and edged closer to her companion like a dog to his fellow. Still he said nothing, but she knew that he had turned and was looking down upon her, and for the first time she was aware of his proximity as a person; she could feel his breath on her forehead. She remembered that her wet shawl and bodice lay on the floor at her feet, and she was naked under her rough blanket. When he spoke again she realised how near he was to her, and his voice came as a shock, confusing suddenly, and unexpected.

"You are very young, Mary Yellan," he said softly: "you are nothing but a chicken with the broken shell still around you. You'll come through your little crisis. Women like you have no need to shed tears over a man encountered once or twice, and the first kiss is not a thing that is remembered. You will forget your friend with his stolen pony very soon. Come now, dry your eyes; you are not the first to bite your nails over a lost lover."

He made light of her problem and counted it as a thing of no account: that was her first reaction to his words. And then she wondered why he had not used the conventional phrases of comfort, said nothing about the blessing of prayer, the peace of God, and life everlasting. She remembered that last ride with him when he had whipped his horse into a fever of speed, and how he had crouched in his seat, with the reins in his hands; and he had whispered words under his breath she had not understood. Again she felt something of the same discomfort she had experienced then; a sensation of uneasiness that she connected instinctively with his freak hair and eyes, as though his physical departure from normality were a barrier between him and the rest of the world. In the animal kingdom a freak was a thing of abhorrence, at once hunted and destroyed, or driven out into the wilderness. No sooner had she thought of this than she reproached herself as narrow and unChristian. He was a fellow creature and a priest of God; but as she murmured an apology to him for having made a fool of herself before him and talking like a common girl from the streets, she reached for her clothes and began to draw them on furtively under cover of the blanket.

"So I was right in my surmise, and all has been quiet at Jamaica Inn since I saw you last?" he said after a while, following some train of thought. "There have been no waggons to disturb your beauty sleep, and the landlord has played alone with his glass and his bottle?"

Mary, still fretful and anxious, with her mind on the man she had lost, brought herself back to reality with an effort. She had forgotten her uncle for nearly ten hours. At once she remembered the full horror of the past week and the new knowledge that had come to her. She thought of the interminable sleepless nights, the long days she had spent alone, and the staring bloodshot eyes of her uncle swung before her again, his drunken smile, his groping hands.

"Mr. Davey," she whispered, "have you ever heard of wreckers?"

She had never said the word aloud before; she had not considered it even, and now that she heard it from her own lips it sounded fearful and obscene, like a blasphemy. It was too dark in the carriage to see the effect upon his face, but she heard him swallow. His eyes were hidden from her under the black shovel hat, and she could see only the dim outline of his profile, the sharp chin, the prominent nose.

"Once, years ago, when I was hardly more than a child, I heard a neighbour speak of them," she said; "and then later, when I was old enough to understand, there were rumours of these things — snatches of gossip quickly suppressed. One of the men would bring back some wild tale after a visit to the north coast, and he would be silenced at once; such talk was forbidden by the older men; it was an outrage to decency. "I believed none of these stories; I asked my mother, and she told me they were the horrible inventions of evil-minded people; such things did not and could not exist. She was wrong. I know now she was wrong, Mr. Davey. My uncle is one of them; he told me so himself."

Still her companion made no reply; he sat motionless, like a stone thine, and she went on again, never raising her voice above a whisper:

"They are in it, every one of them, from the coast to the Tamar bank; all those men I saw that first Saturday in the bar at the inn. The gipsies, poachers, sailors, the pedlar with the broken teeth. They've murdered women and children with their own hands; they've held them under the water; they've killed them with rocks and stones. Those are death waggons that travel the road by night, and the goods they carry are not smuggled casks alone, with brandy for some and tobacco for another, but the full cargoes of wrecked ships bought at the price of blood, the trust and the possession of murdered men. And that's why my uncle is feared and loathed by the timid people in the cottages and farms, and why all doors are barred against him, and why the coaches drive past his house in a cloud of dust. They suspect what they cannot prove. My aunt lives in mortal terror of discovery; and my uncle has only to lose himself in drink before a stranger and his secret is split to the four winds. There, Mr. Davey; now you know the truth about Jamaica Inn."

She leant back, breathless, against the side of the carriage, biting her lips and twisting her hands in an emotion she could not control, exhausted and shaken by the torrent of words that had escaped her; and somewhere in the dark places of her mind an image fought for recognition and found its way into the light, having no mercy on her feelings; and it was the face of Jem Merlyn, the man she loved, grown evil and distorted, merging horribly and finally into that of his brother.

The face beneath the black shovel hat turned towards her; she caught a sudden flicker of the white lashes, and the lips moved.

"So the landlord talks when he is drunk?" he said, and it seemed to Mary that his voice lacked something of its usual gentle quality; it rang sharper in tone, as though pitched on a higher note; but when she looked up at him his eyes stared back at her, cold and impersonal as ever.

"He talks, yes," she answered him. "When my uncle has lived on brandy for five days he'll bare his soul before the world. He told me so himself, the very first evening I arrived. He was not drunk then. But four days ago, when he had woken from his first stupor, and he came out to the kitchen after midnight, swaying on his two feet — he talked then. That's why I know. And that's perhaps why I've lost faith in humanity, and in God, and in myself; and why I acted like a fool today in Launceston."

The gale had increased in force during their conversation, and now with the bend in the road the carriage headed straight into the wind and was brought almost to a standstill. The vehicle rocked on its high wheels, and a sudden shower spattered against the windows like a handful of pebbles. There was no particle of shelter now; the moor on either hand was bare and unprotected, and the scurrying clouds flew fast over the land, tearing themselves asunder on the tors. There was a salt, wet tang in the wind that had come from the sea fifteen miles away.

Francis Davey leant forward in his seat. "We are approaching Five Lanes and the turning to Altarnun," he said; "the driver is bound to Bodmin and will take you to Jamaica Inn. I shall leave you at Five Lanes and walk down into the village. Am I the only man you have honoured with your confidence, or do I share it with the landlord's brother?"

Again Mary could not tell if there was irony or mockery in his voice. "Jem Merlyn knows," she said unwillingly. "We spoke of it this morning. He said little, though, and I know he is not friendly with my uncle. Anyway, it doesn't matter now; Jem rides to custody for another crime."

"And suppose he could save his own skin by betraying his brother, what then, Mary Yellan? There is a consideration for you."

Mary started. This was a new possibility, and for a moment she clutched at the straw. But the vicar of Altarnun must have read her thoughts, for, glancing up at him for confirmation of her hopes, she saw him smile, the thin line of his mouth breaking for a moment out of passivity, as though his face were a mask and the mask had cracked. She looked away, uncomfortable, feeling like one who stumbles unawares upon a sight forbidden.

"That would be a relief to you and to him, no doubt," continued the vicar, "if he had never been involved. But there is always the doubt, isn't there? And neither you nor I know the answer to that question. A guilty man does not usually tie the rope around his own neck."

Mary made a helpless movement with her hands, and he must have seen the despair in her face, for his voice became gentle again that had been harsh hitherto, and he laid his hand on her knee. "Our bright days are done, and we are for the dark," he said softly. "If it were permitted to take our text from Shakespeare, there would be strange sermons preached in Cornwall tomorrow, Mary Yellan. Your uncle and his companions are not members of my congregation, however, and if they were they would not understand me. You shake your head at me. I speak in riddles. 'This man is no comforter,' you say; 'he is a freak with his white hair and eyes.' Don't turn away; I know what you think. I will tell you one thing for consolation, and you can make of it what you will. A week from now will bring the New Year. The false lights have flickered for the last time, and there will be no more wrecks; the candles will be blown."

"I don't understand you," said Mary. "How do you know this, and what has the New Year to do with it?"

He took his hand from her and began to fasten his coat preparatory to departure. He lifted the sash of the window and called to the driver to rein in his horse, and the cold air rushed into the carriage with a sting of frozen rain. "I return tonight from a meeting in Launceston," he said, "which was but a sequel to many other similar meetings during the past few years. And those of us present were informed at last that His Majesty's Government was prepared to take certain steps during the coming year to patrol the coasts of His Majesty's country. There will be watchers on the cliffs instead of flares, and the paths known only at present to men like your uncle and his companions will be trodden by officers of the law.

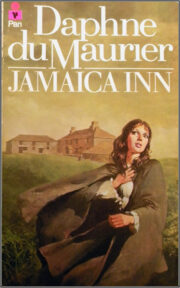

"Jamaica Inn" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Jamaica Inn". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Jamaica Inn" друзьям в соцсетях.