She waited. They did not move. There was no sound. Only the sea broke in its inevitable monotony upon the shore, sweeping the strand and returning again, the line of breakers showing thin and white against the black night.

The mist began to lift very slowly, disclosing the narrow outline of the bay. Rocks became more prominent, and the cliffs took on solidity. The expanse of water widened, opening from a gulf to a bare line of shore that stretched away interminably. To the right, in the distance, where the highest part of the cliff sloped to the sea, Mary made out a faint pinprick of light. At first she thought it a star, piercing the last curtain of dissolving mist, but reason told her that no star was white, nor ever swayed with the wind on the surface of a cliff. She watched it intently, and it moved again; it was like a small white eye in the darkness. It danced and curtseyed, storm tossed, as though kindled and carried by the wind itself, a living flare that would not be blown. The group of men on the shingle below heeded it not; their eyes were turned to the dark sea beyond the breakers.

And suddenly Mary was aware of the reason for their indifference, and the small white eye that had seemed at first a thing of friendliness and comfort, winking bravely alone in the wild night, became a symbol of horror.

The star was a false light placed there by her uncle and his companions. The pinprick gleam was evil now, and the curtsey to the wind became a mockery. In her imagination the light burnt fiercer, extending its beam to dominate the cliff, and the colour was white no more, but old and yellow like a scab. Someone watched by the light so that it should not be extinguished. She saw a dark figure pass in front of it, obscuring the gleam for a moment, and then it burnt clear again. The figure became a blot against the grey face of the cliff, moving quickly in the direction of the shore. Whoever it was climbed down the slope to his companions on the shingle. His action was hurried, as though time pressed him, and he was careless in the manner of his coming for the loose earth and stones slid away from under him, scattering down onto the beach below. The sound startled the men beneath, and for the first time since Mary had watched them they withdrew their attention from the incoming tide and looked up to him. Mary saw him put his hands to his mouth and shout, but his words were caught up in the wind and did not come to her. They reached the little group of men waiting on the shingle, who broke up at once in some excitement, some of them starting halfway up the cliff to meet him; but when he shouted again and pointed to the sea, they ran down towards the breakers, their stealth and silence gone for the moment, the sound of their footsteps heavy on the shingle, their voices topping one another above the crash of the sea. Then one of them — her uncle it was; she recognised his great loping stride and massive shoulders — held up his hand for silence; and they waited, all of them, standing upon the shingle with the waves breaking beyond their feet; spread out in a thin line they were, like crows, their black forms outlined against the white beach. Mary watched with them; and out of the mist and darkness came another pinprick of light in answer to the first. This new light did not dance and waver as the one on the cliff had done; it dipped low and was hidden, like a traveller weary of his burden, and then it would rise again, pointing high to the sky, a hand flung into the night in a last and desperate attempt to break the wall of mist that hitherto had defied penetration. The new light drew nearer to the first. The one compelled the other. Soon they would merge and become two white eyes in the darkness. And still the men crouched motionless upon the narrow strand, waiting for the lights to close with one another.

The second light dipped again; and now Mary could see the shadowed outline of a hull, the black spars like fingers spreading above it, while a white surging sea combed beneath the hull, and hissed, and withdrew again. Closer drew the mast light to the flare upon the cliff, fascinated and held, like a moth coming to a candle.

Mary could bear no more. She scrambled to her feet and ran down upon the beach, shouting and crying, waving her hands above her head, pitting her voice against the wind and the sea, which tossed it back to her in mockery. Someone caught hold of her and forced her down upon the beach. Hands stifled her. She was trodden upon and kicked. Her cries died away, smothered by the coarse sacking that choked her, and her arms were dragged behind her back and knotted together, the rough cord searing her flesh.

They left her then, with her face in the shingle, the breakers sweeping towards her not twenty yards away; and as she lay there helpless, the breath knocked from her and her scream of warning strangled in her throat, she heard the cry that had been hers become the cry of others, and fill the air with sound. The cry rose above the searing smash of the sea and was seized and carried by the wind itself; and with the cry came the tearing splinter of wood, the horrible impact of a massive live thing finding resistance, the shuddering groan of twisting, breaking timber.

Drawn by a magnet, the sea hissed away from the strand, and a breaker running high above its fellows flung itself with a crash of thunder upon the lurching ship. Mary saw the black mass that had been a vessel roll slowly upon its side, like a great flat turtle; the masts and spars were threads of cotton, crumpled and fallen. Clinging to the slippery, sloping surface of the turtle were little black dots that would not be thrown; that stuck themselves fast to the splintering wood like limpets; and, when the heaving, shuddering mass beneath them broke monstrously in two, cleaving the air, they fell one by one into the white tongues of the sea, little black dots without life or substance.

A deadly sickness came upon Mary, and she closed her eyes, her face pressed into the shingle. The silence and the stealth were gone; the men who had waited during the cold hours waited no more. They ran like madmen hither and thither upon the beach, yelling and screaming, demented and inhuman. They waded waist deep into the breakers, careless of danger, all caution spent; snatching at the bobbing, sodden wreckage borne in on the surging tide.

They were animals, fighting and snarling over lengths of splintered wood; they stripped, some of them, and ran naked in the cold December night, the better to fight their way into the sea and plunge their hands amongst the spoil that the breakers tossed to them. They chattered and squabbled like monkeys, tearing things from one another; and one of them kindled a fire in the corner by the cliff, the flame burning strong and fierce in spite of the mizzling rain. The spoils of the sea were dragged up the beach and heaped beside it. The fire cast a ghastly light upon the beach, throwing a yellow brightness that had been black before, and casting long shadows down the beach where the men ran backwards and forwards, industrious and horrible.

When the first body was washed ashore, mercifully spent and gone, they clustered around it, diving amongst the remains with questing, groping hands, picking it clean as a bone; and, when they had stripped it bare, tearing even at the smashed fingers in search of rings, they abandoned it again, leaving it to loll upon its back in the scum where the tide had been.

Whatever had been the practice hitherto, there was no method in their work tonight. They robbed haphazard, each man for himself; crazy they were and drunk, mazed with this success they had not planned — dogs snapping at the heel of their master whose venture had proved a triumph, whose power this was, whose glory. They followed him where he ran naked amongst the breakers, the water streaming from the hair on his body, a giant above them all.

The tide turned, the water receded, and a new chill came upon the air. The light that swung above them on the cliff, still dancing in the wind, like an old mocking man whose joke has long been played, turned pallid now and dim. A grey colour came upon the water and was answered by the sky. At first the men did not notice the change; they were delirious still, intent upon their prey. And then Joss Merlyn himself lifted his great head and sniffed the air, turning about him as he stood, watching the clear contour of the cliffs as the darkness slipped away; and he shouted suddenly, calling the men to silence, pointing to the sky that was leaden now and pale. They hesitated, glancing once more at the wreckage that surged and fell in the trough of the sea, unclaimed as yet and waiting to be salved; and then they turned with one accord and began to run up the beach towards the entrance of the gully, silent once more, without words or gesture, their faces grey and scared in the broadening light. They had outstayed their time. Success had made them careless. The dawn had broken upon them unawares, and by lingering overlong they had risked the accusation which daylight would bring to them. The world was waking up around them; night that had been their ally, covered them no more.

It was Joss Merlyn who pulled the sacking away from her mouth and jerked Mary to her feet. Seeing that her weakness had become part of her now, and could not be withstood, for she could neither stand alone nor help herself in any way, he cursed her furiously, glancing behind him at the cliffs that every minute became harder, more distinct; and then he bent down to her, for she had stumbled to the ground again, and threw her over his shoulder as he would a sack. Her head lolled without support, her arms lifeless, and she felt his hands pressing into her scarred side, bruising it once again, rubbing the numb flesh that had lain upon the shingle. He ran with her up the strand to the entrance of the gully; and his companions caught up already in a mesh of panic, flung the remnants of spoil they had snatched from the beach upon the backs of the three horses tethered there. Their movements were feverish and clumsy, and they worked without direction, as though unhinged, lacking all sense of order; while the landlord, sober now from necessity and strangely ineffectual, cursed and bullied them to no avail. The carriage, stuck in the bank halfway up the gully, resisted their efforts to extract it, and this sudden reverse to their fortune increased the panic and stampede. Some of them began to scatter up the lane, forgetting everything in a blind concentration on personal safety. Dawn was their enemy, and more easily withstood alone, in the comparative security of ditch and hedge, than in the company of five or six upon the road. Suspicion would lie in numbers here on the coast, where every face was known and strangers were remarkable; but a poacher, or tramp, or gypsy could make his way alone, finding his own cover and his own path. These deserters were cursed by those who remained, struggling with the carriage, and now, through stupidity and panic, the vehicle was wrenched from the bank in so rough a manner that it overturned, falling upon one side and smashing a wheel.

This final disaster let loose pandemonium in the gullyway. There was a wild rush to the remaining farm cart that had been left further up the lane, and to the already over-burdened horses. Someone, still obedient to the leader and with a sense of necessity, put fire to the broken carriage, whose presence in the lane screamed danger to them all, and the riot that followed — fight between man and man for the possession of the farm cart that might yet carry them away inland — was a hideous scrap of tooth and nail, of teeth smashed by stones, of eyes cut open by broken glass.

Those who carried pistols now had the advantage, and the landlord, with his remaining ally Harry the pedlar by his side, stood with his back to the cart and let fly amongst the rabble, who, in the sudden terror of pursuit that would follow with the day, looked upon him now as an enemy, a false leader who had brought them to destruction. The first shot went wide and stubbed the soft bank opposite; but it gave one of the opponents a chance to cut the landlord's eye open with a jagged flint. Joss Merlyn marked his assailant with his second shot, spattering him in mid-stomach, and while the fellow doubled up in the mud amongst his companions, mortally wounded and screaming like a hare, Harry the pedlar caught another in the throat, the bullet ripping the windpipe, the blood spouting jets like a fountain.

It was the blood that won the cart for the landlord; for the remaining rebels, hysterical and lost at the sight of their dying fellows, turned as one man and scuttled like crabs up the twisting lane, intent only on putting a safe distance between themselves and their late leader. The landlord leant against the cart with smoking, murderous pistol, the blood running freely from the cut on his eye. Now that they were alone, he and the pedlar wasted little time. What wreckage had been salved and brought to the gully they threw upon the car beside Mary — miscellaneous odds and ends, useless and unprofitable, the main store still down on the beach and washed by the tide. They dared not risk the fetching of it, for that would be the work of a dozen men, and already the light of day had followed the early dawn and made clear the countryside. There was not a moment to spare.

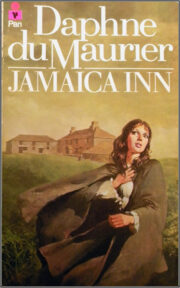

"Jamaica Inn" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Jamaica Inn". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Jamaica Inn" друзьям в соцсетях.