“Sounds good.”

Prateek gives me instructions. After a cold shower, I head outside, Chaudhary trailing behind me with dire warnings of “pickpockets, thieves, prostitutes, and roving gangs.” He ticks off the threats on his thick fingers. “They will accost you.”

I assure him I can take it, and in any case the only people to accost me are begging mothers, who congregate in the grassy medians in the center of the shady streets, asking for money to buy formula for the sleeping babies in their arms.

This part of Mumbai reminds me a bit of London with its decaying colonial buildings, except it’s supersaturated with color: the women’s saris, the marigold-festooned temples, the crazily painted buses. It’s like everything absorbs and reflects the bright sun.

From the outside, Crawford Market seems like another building plucked out of old England, but inside it is all India: bustling commerce and yet more surreally bright colors. I walk around the fruit stalls, the clothing stalls, making my way toward the electronics stalls where Prateek told me to find him. I feel a tap on my shoulder.

“Lost?” Prateek asks, a grin splitting his face.

“Not in a bad way.”

He frowns at that, confounded. “I was worried,” he says. “I wanted to call you but I don’t have your mobile.”

“My mobile doesn’t work here.”

The smile returns. “As it happens, we have many mobile phones at my uncle’s electronics stall.”

“So that’s why you lured me here?” I tease.

Prateek looks insulted. “Of course not. How did I know you lacked a phone?” He gestures to the stalls around us. “You can buy from another stall.”

“I’m joking, Prateek.”

“Oh.” He takes me to his uncle’s stall, crammed to the ceiling with cellphones, radios, computers, knockoff iPads, televisions, and more. He introduces me to his uncle and buys us all cups of tea from the chai-wallah, the traveling tea salesman. Then he takes me to the back of the stall and we sit down on a couple of rickety stools.

“You work here?”

“On Mondays, Tuesdays, and Fridays.”

“What do you do the other days?”

He does the head nod/wag thing. “I’m studying accounting. I also work for my mother some days. And I help my cousin sometimes to find goreh for movies.”

“Goreh.”

“White people, like you. It’s why I was at the airport today. I had to drive my cousin.”

“Why didn’t you ask me?” I joke.

“Oh, I am not a casting director, or even an assistant to an assistant. I just drove Rahul to the airport to look for backpackers needing money. Do you need money, Willem?”

“No.”

“I did not think so. You are staying at the Bombay Royale. Very high class. And visiting your mother. Where is your father?” he asks.

It’s been a while since anyone asked me that. “He’s dead.”

“Oh, mine, too,” Prateek says almost cheerfully. “But I have many uncles. And cousins. You?”

I almost say yes. I have an uncle. But how do you explain Daniel? Not so much a black sheep as an invisible one, eclipsed by Bram. And Yael. Daniel, the footnote to Yael and Bram’s story, the small print that nobody bothers to read. Daniel, the younger, scragglier, messier, less directed—and not to forget, shorter—brother. Daniel, the one relegated to the backseat of the Fiat, and consequently, it seemed, the backseat of life.

“Not much family,” is all I say in the end, bookending my vagueness with a shrug, my own version of the head wag.

Prateek presents me a choice of phones. I choose one and buy a SIM card. He immediately programs his number and, for good measure, his uncle’s into it. We finish our tea and then he announces, “Now I think you must go to the movies.”

“I just got here.”

“Exactly. What is more Indian than that? Fourteen million people—”

“A day go to the movies here,” I interrupt. “Yes, I’ve been told.”

He pulls a heap of magazines out of his bag, the same ones I’d seen in the car. Magna. Stardust. He opens one and shows me pages of attractive people, all with extremely white teeth. He rattles off a bunch of names, dismayed that I know none of them.

“We will go now,” he declares.

“Don’t you have to work?”

“In India, work is the master, but the guest is god,” Prateek says. “Besides, between the phone and taxi . . .” He smiles. “My uncle will not object.” He opens a newspaper. “Dil Mera Golmaal is on. So is Gangs of Wasseypur. Or Dhal Gaya Din. What do you think, Baba?”

Prateek and his uncle carry on a spirited conversation in a mix of Hindi and English, debating the merits and deficits of all three films. Finally they settle on Dil Mera Golmaal.

The theater is an art deco building with peeling white paint, not unlike the revival houses Saba used to take me to when he visited. I buy our tickets and our popcorn. Prateek promises to translate in return.

The film—a sort of convoluted take on Romeo and Juliet, involving warring families, gangsters, a terrorist plot to steal nuclear weapons, plus countless explosions and dance numbers—doesn’t require much translation. It is both nonsensical and oddly self-explanatory.

Still, Prateek gives it a shot. “That man is that one’s brother but he doesn’t know it,” he whispers. “One is evil, the other is good, and the girl is engaged to the bad one, but she loves the good one. Her family hates his family and his family hates her family but they don’t really because the feud has to do with the other one’s father, who engineered the feud when he stole the baby at birth, you see. He is also a terrorist.”

“Right.”

Then there’s a dance number and a fight scene and then suddenly we are in the desert. “Dubai,” Prateek whispers.

“Why, exactly?” I ask.

Prateek explains that the oil consortium is there. As are the terrorists.

There are several scenes in the desert, including a duel between two monster trucks that Henk would appreciate.

Then the film switches abruptly to Paris. One moment, there’s a generic shot of the Seine. And then, a second later, a shot down the banks of the river. Then we see the heroine and the good twin brother, who, Prateek explains, have gotten married and fled together. They break out into song. But they’re no longer on the Seine; now they are on one of the arched bridges that span the canals in Villette. I recognize it. Lulu and I cruised under it, sitting side by side, our legs knocking against the hull. Occasionally, we’d accidentally knock ankles and there had been something electric about it, a turn-on, just in that.

I feel it now in this musty theater. Almost like a reflex, my thumb goes to the inside of my wrist, but the gesture is meaningless, here in the dark.

Soon the song is over and we’re back in India for the grand finale when the families reunite and reconcile and there’s another wedding ceremony and a big dance number. Unlike Romeo and Juliet, these lovers get a happy ending.

After the movie, we walk through the crowded streets. It’s dark now, and the heat’s gone wavy. We meander our way to a wide crescent of sand. “Chowpatty Beach,” Prateek tells me, pointing out the luxury highrises on Marine Drive. They sparkle like diamonds against the slender curving wrist of the bay.

It’s a carnival atmosphere with all the food vendors and clowns and balloon shapers and the furtive lovers taking advantage of the darkness to steal kisses behind a palm tree. I try not to watch them. I try not to remember stealing kisses. I try not to remember that first kiss. Not her lips, but that birthmark on her wrist. I’d been wanting to kiss it all day. Somehow, I knew exactly what it would taste like.

The water laps against the shore. The Arabian Sea. The Atlantic Ocean. Two oceans between us. And still not enough.

Twenty-three

After four days, Yael finally has a day off. Instead of waking up from my fold-up bed to find her rushing out the door, I see her in her pajamas. “I’ve ordered up breakfast,” she says in that crisp voice of hers, the gutturalness of her Israeli accent ironed out from all the years of speaking English.

There’s a knock at the door. Chaudhary, who seems to always work and to do every single job here, shuffles in, pushing a trolley. “Breakfast, Memsahib,” he announces.

“Thank you, Chaudhary,” Yael says.

He studies the two of us. Then shakes his head. “He is nothing like you, Memsahib,” he says.

“He looks like his baba,” Yael replies.

I know it’s true, but it’s strange to hear her say it. Though not as strange, I’d imagine, as seeing the face of her dead husband staring back at her. Sometimes when I’m feeling charitable, I’ll justify this as the reason she’s put such distance between us these last three years. Then the less charitable side of me will ask, What about the eighteen years before that?

With a dramatic flourish, Chaudhary sets out toast, coffee, tea, and juice. Then he backs out of the door.

“Does he ever leave?” I ask.

“No, not really. His children are all overseas and his wife passed. So he works.”

“Sounds miserable.”

She gives me one of her inscrutable looks. “At least he has a purpose.”

She flips open the newspaper. Even that is colorful, a salmony shade of pink. “What have you been doing the last few days?” she asks me as she eyes the headlines.

I went back to Chowpatty Beach, the markets around Colaba, the Gateway. I went to another movie with Prateek. I’ve wandered mostly. Without purpose. “This and that,” I say.

“So today we do that and this,” she replies.

Downstairs, we are besieged by the usual congregation of beggars. “Ten rupees,” a woman carrying a sleeping baby says. “For formula for my baby. You come with me to buy it.”

I start to pull out money, but Yael snaps at me to stop and then snaps at the woman in Hindi.

I don’t say a word. But my expression must give me away, because Yael gives an exasperated explanation. “It’s a scam, Willem. The babies are props. The women are part of begging rings, run by organized crime syndicates.”

I look at the woman, now standing across from the Taj Hotel, and shrug. “So? She still needs the money.”

Yael nods and frowns. “Yes, she does. And the baby needs food, no doubt, but neither of them will get what they need. If you bought milk for that woman, you’d pay an inflated price, and you’d get an inflated sense of goodwill. You helped a mother feed her baby. What could be better?”

I don’t say anything, because I’ve been giving them money every day and now I feel foolish for it.

“As soon as you walk away, the milk’s returned to the shop. And your money? The shopkeeper gets a cut; the crime bosses get a cut. The women, the women are indentured, and they get nothing. As for what happens to babies . . .” She trails off ominously.

“What happens to the babies?” The question pops out before I realize I might not want to know the answer.

“They die. Sometimes of malnutrition. Or sometimes of pneumonia. When life is so tenuous, something small might do it.”

“I know,” I say. Sometimes even when life isn’t that tenuous, I think and I wonder if she’s thinking the same thing.

“In fact, the day you arrived, I was late because of an emergency with one of those very children.” She doesn’t elaborate, leaving it for me to put the pieces together.

Yael’s non-admission manages to make me feel retroactively guilty for faulting her—there was something more important—and bitter—there always is something more important. But mostly it makes me tired. Couldn’t she have just told me and saved me the trouble of my guilt and bitterness?

Then again, sometimes I think that guilt and bitterness may be Yael’s and my true common language.

• • •

Our first stop is the Shree Siddhivinayak Temple, an ornate wedding cake of a temple that is being attacked by a tourist horde of ants. Yael and I take our place among the masses and push into a stuffy gold hall, wending our way to a flower-covered statue of the elephant god. He’s beet-red, as if embarrassed, or maybe he’s just hot, too.

“Ganesha,” Yael tells me.

“The remover of obstacles.”

She nods.

All around us, people are laying garlands around the shrine or singing or praying.

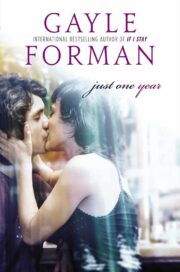

"Just One Year" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Just One Year". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Just One Year" друзьям в соцсетях.