I take her suitcase. “Come on. I’ll take you home.”

• • •

The last time I was at the boat, it was September; I got as far as the pier before I rode away. It looked so empty, so haunted, like it was mourning his loss, too, which made a certain sense because he built it. Even the clematis that Saba had planted—“because even a cloud-soaked country needs shade”—which had once run riot over the deck, had gone shriveled and brown. If Saba had been here, he would’ve cut it back. It’s what he always did when he came back in the summer and found the plants ailing in his absence.

The clematis is back now, bushy and wild, dropping purple petals all over the deck. The deck is full of other blooms, trellises, vines, arbors, pots, viny flowering things.

“This was my home,” I tell Kate. “It’s where I grew up.”

Kate was mostly quiet on the tram ride over. “It’s beautiful,” she says.

“My father built it.” I can see Bram’s winked smile, hear him announce as if to no one: I need a helper this morning. Yael would hide under the duvet. Ten minutes later, I’d have a drill in my hand. “I helped, though. I haven’t been here in a long time. Your hotel is just around the corner.”

“What a coincidence,” she says.

“Sometimes I think everything is.”

“No. Everything isn’t.” She looks at me. Then she asks, “So what’s wrong, Willem? Stage fright?”

“No.”

“Then what is it?”

I tell her. About getting the call this morning. About that moment in the first rehearsal, finding something new, finding something real in Orlando, and then having it all go to hell.

“Now I just want to get up there, get through it, get it over with,” I tell her. “With as few witnesses as possible.”

I expect sympathy. Or Kate’s undecipherable yet somehow resonant acting advice. Instead, I get laughter. Snorts and hiccups of it. Then she says, “You have got to be kidding me.”

I am not kidding. I don’t say anything.

She attempts to contain herself. “I’m sorry, but the opportunity of a lifetime drops into your lap—you finally get one of your glorious accidents—and you’re going to let a lousy piece of direction derail you.”

She is making it seem so slight, a bad piece of advice. But it feels like so much more. A wallop in the face, not a piece of bad direction, but a redirection. This is not the way. And just when I thought I had really found something. I try to find the words to explain this . . . this betrayal. “It’s like finding the girl of your dreams,” I begin.

“And realizing you never caught her name?” Kate finishes.

“I was going to say finding out she was actually a guy. That you had it so completely wrong.”

“That only happens in movies. Or Shakespeare. Though it’s funny you mention the girl of your dreams, because I’ve been thinking about your girl, the one you were chasing in Mexico.”

“Lulu? What does she have to do with this?”

“I was telling David about you and your story and he asked this ridiculously simple question that I’ve been obsessing about ever since.”

“Yes?”

“It’s about your backpack.”

“You’ve been obsessing about my backpack?” I make it sound like a joke, but all of a sudden, my heart has sped up. Pulled a runner. Dicked her over. I can hear Tor’s disgust, in that Yorkshire accent of hers.

“Here’s the thing: If you were just going out for coffee or croissants or to book a hotel room or whatever, why did you take your backpack, with all your things in it, with you?”

“It wasn’t a big backpack. You saw it. It was the same one I had in Mexico. I always travel light like that.” I’m talking too fast, like someone with something to hide.

“Right. Right. Traveling light. So you can move on. But you were going back to that squat, and you had to climb, if I recall, out of a second-story building. Isn’t that right?” I nod. “And you brought a backpack with you? Wouldn’t it have been easier to leave most of your things there? Easier to climb. At the very least, it would’ve been a sure sign that you intended to return.”

I was there on that ledge, one leg in, one leg out. A gust of wind, so sharp and cold after all that heat, knifed through me. Inside, I heard rustling as Lulu rolled over and wrapped herself in the tarp. I’d watched her for a moment, and as I did, this feeling had come over me stronger than ever. I’d thought, Maybe I should just wait for her to wake up. But I was already out the window and I could see a patisserie down the way.

I’d landed heavily, in a puddle, rainwater sloshing around my feet. When I’d looked back up at the window, the white curtain flapping in the gusty breeze, I’d felt both sadness and relief, the oppositional tug of heaviness and lightness, one lifting me up, one pushing me down. I understood then, Lulu and I had started something, something I’d always wanted, but also something I was scared of getting. Something I wanted more of. And, also, something I wanted to get away from. The truth and its opposite.

I set off for the patisserie not quite knowing what to do, not quite knowing if I should go back, stay another day, but knowing if I did, it would break all this wide open. I bought the croissants, still not knowing what to do. And then I turned a corner and there were the skinheads. And in a twisted way, I was relieved: They would make the decision for me.

Except as soon as I woke up in that hospital, unable to remember Lulu, or her name, or where she was, but desperate to find her, I understood that it was the wrong decision.

“I was coming back,” I tell Kate. But there’s a razor of uncertainty in my voice, and it cuts my deception wide open.

“You know what I think, Willem?” Kate says, her voice gentle. “I think acting, that girl, it’s the same thing. You get close to something and you get spooked, so you find a way to distance yourself.”

In Paris, the moment when Lulu had made me feel the safest, when she had stood between me and the skinheads, when she had taken care of me, when she became my mountain girl, I’d almost sent her away. That moment, when we’d found safety, I’d looked at her, the determination burning in her eyes, the love already there, improbably after just one day. And I felt it all—the wanting and the needing—but also the fear because I’d seen what losing this kind of thing could do. I wanted to be protected by her love, and to be protected from it.

I didn’t understand then. Love is not something you protect. It’s something you risk.

“You know the irony about acting?” Kate muses. “We wear a thousand masks, are experts at concealment, but the one place it’s impossible to hide is on stage. So no wonder you’re freaked out. And Orlando, well now!”

She’s right, again. I know she is. Petra didn’t do anything today except give me an excuse to pull another runner. But the truth of it is I didn’t really want to pull a runner that day with Lulu. And I don’t want to pull one now, either.

“What’s the worst that happens if you do it your way tonight?” Kate asks.

“She fires me.” But if she does, it’ll be my action that decides it. Not my inaction. I start to smile. It’s tentative, but it’s real.

Kate matches mine with a big American version. “You know what I say: Go big or go home.”

I look at the boat; it’s quiet, but the garden is so lush and well-tended in a way that it never was with us. It is a home, not mine, but someone else’s now.

Go big or go home. I heard Kate say that before and didn’t quite get it. But I understand it now, though I think on this one, Kate has it wrong. Because for me, it’s not go big or go home. It’s go big and go home.

I need to do one to do the other.

Forty-eight

Backstage. It’s the usual craziness, only I feel strangely calm. Linus hustles me to the makeshift dressing room where I change out of my street clothes into Orlando’s clothes, hastily altered to fit me. I put on my makeup. I fold my clothes into the lockers behind the stage. My jeans, my shirt, Lulu’s watch. I hold it in my hand one second longer, feel the ticking vibrate against my palm, and then I put it in the locker.

Linus gathers us into a circle. There are vocal exercises. The musicians tune their guitars. Petra barks last-minute direction, about finding my light and keeping the focus and the other actors supporting me, and just doing my best. She is giving me a piercing, worried look.

Linus calls five minutes and puts on his headset, and Petra walks away. Max has come backstage for tonight’s performance and is sitting on a three-legged stool in the wings. She doesn’t say anything, but just looks at me and kisses two fingers and holds them up in the air. I kiss the same two on my hand and hold them up to her.

“Break a leg,” someone whispers in my ear. It’s Marina, come up behind me. Her arms quickly encircle me from behind as she kisses me somewhere between my ear and my neck. Max catches this and smirks.

“Places!” Linus calls. Petra is nowhere to be seen. She disappears before curtain and won’t reappear until the show is over. Vincent says she goes somewhere to pace, or smoke, or disembowel kittens.

Linus grabs my wrist. “Willem,” he says. I spin to look at him. He gives a small squeeze and nods. I nod back. “Musicians, go!” Linus commands into his headset.

The musicians start to play. I take my place at the side of stage.

“Light cue one, go,” Linus says.

The lights go up. The audience hushes.

Linus: “Orlando, go!”

I hesitate a moment. Breathe, I hear Kate say. I take a breath.

My heart hammers in my head. Thud, thud, thud. I close my eyes and can hear the ticking of Lulu’s watch; it’s as if I’m still wearing it. I stop and listen to them both before I walk onto the stage.

And then time just stops. It is a year and a day. One hour and twenty-four. It is time, happening, all at once.

The last three years solidify into this one moment, into me, into Orlando. This bereft young man, missing a father, without a family, without a home. This Orlando, who happens upon this Rosalind. And even though these two have known each other only moments, they recognize something in each other.

“The little strength that I have, I would it were with you,” Rosalind says, cracking it all wide open.

Who takes care of you? Lulu asked, cracking me wide open.

“Wear this for me,” Marina says as Rosalind, handing me the prop chain from around her neck.

I’ll be your mountain girl and take care of you, Lulu said, moments before I took the watch from her wrist.

Time is passing. I know it must be. I enter the stage, I exit the stage. I make my cues, hit my marks. The sun dips across the sky and then dances toward the horizon and the stars come out, the floodlights go on, the crickets sing. I sense it happening as I drift above it somehow. I am only here, now. This moment. On this stage. I am Orlando, giving myself to Rosalind. And I am Willem, too, giving myself to Lulu, in a way that I should’ve done a year ago, but couldn’t.

“You should ask me what time o’ day: there’s no clock in the forest,” I say to my Rosalind.

You forget, time doesn’t exist anymore. You gave it to me, I said to my Lulu.

I feel the watch on my wrist that day in Paris; I hear it ticking in my head now. I can’t tell them apart, last year, this year. They are one and the same. Then is now. Now is then.

“I would not be cured, youth,” my Orlando tells Marina’s Rosalind.

“I would cure you, if you would but call me Rosalind,” Marina replies.

I’ll take care of you, Lulu promised.

“By my troth, and in good earnest, and so God mend me, and by all pretty oaths that are not dangerous,” Marina’s Rosalind says.

I escaped danger, Lulu said.

We both did. Something happened that day. It’s still happening. It’s happening up here on this stage. It was just one day and it’s been just one year. But maybe one day is enough. Maybe one hour is enough. Maybe time has nothing at all to do with it.

“Fair youth, I would I could make thee believe I love,” my Orlando tells Rosalind.

Define love, Lulu had demanded. What would “being stained” look like?

Like this, Lulu.

It would look like this.

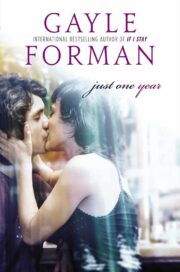

"Just One Year" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Just One Year". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Just One Year" друзьям в соцсетях.