The theater complex is packed, people spilling out the front doors. We fight our way through the crowds to the box office. And that’s when I see her: Lulu.

Not my Lulu. But the Lulu I named her for. Louise Brooks. The theater has lots of old movie posters in the lobby, but I’ve never seen this one, which isn’t on the wall but is propped up on an easel. It’s a still shot from Pandora’s Box, Lulu, pouring a drink, her eyebrow raised in amusement and challenge.

“She’s pretty.” I look up. Behind me is Lien, W’s punked-out math major girlfriend. No one can quite get over how he did it, but apparently they fell in love over numbers theory.

“Yeah,” I agree.

I look closer at the poster. It is advertising a Louise Brooks film retrospective. Pandora’s Box is on tonight.

“Who was she?” Lien asks.

“Louise Brooks,” Saba had said. “Look at those eyes, so much delight, you know there’s sadness to hide.” I was thirteen, and Saba, who hated Amsterdam’s mercurial wet summers, had just discovered the revival cinemas. That summer was particularly dreary, and Saba had introduced me to all the silent film stars: Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Rudolph Valentino, Pola Negri, Greta Garbo, and his favorite, Louise Brooks.

“Silent film star,” I tell Lien. “There’s a festival on. Unfortunately it’s tonight.”

“We could see that instead,” she says. I can’t tell if her tone is sarcastic; she’s as dry as W is. But when I get to the front of the line to buy the tickets, I find myself asking for five to Pandora’s Box.

At first, the boys are amused. They think I’m joking, until I point to the poster and explain about the retrospective. Then they are not so amused.

“There’s a live piano player,” I say.

“Is that supposed to make us feel better?” Henk asks.

“No way I’m seeing this,” W adds.

“What if I wanted to see it?” Lien interjects.

I offer her a silent thank-you and she gives me a perplexed eyebrow raise in return, showing off her piercing. W acquiesces and the rest follow suit.

Upstairs, we take our seats. In the quiet, you can hear the explosions from the adjacent theater and I can see Henk’s eyes go wistful.

The lights go down and the piano player starts in with the overture and Lulu’s face fills the screen. The movie starts, all scratchy and black and white; you can almost hear it crackle like an old LP. But there is nothing old about Lulu. She’s timeless, flirting gaily in the nightclub, being caught with her lover, shooting her husband on their wedding night.

It’s strange because I’ve seen this film before, a few times. I know exactly how it ends, but as it goes on, a tension starts to build, a suspense, churning uncomfortably in my gut. It takes a certain kind of naiveté, or perhaps just stupidity, to know how things will end and still hope otherwise.

Fidgety, I shove my hands into my pockets. Though I try not to, my mind keeps going to the other Lulu on that hot August night. I tossed her the coin, as I’d done to so many other girls. But unlike the other girls who always came back—lingering by our makeshift stage to return my very valuable worthless coin and to see what it might buy—Lulu didn’t.

That should’ve been my first sign that the girl could see through my acts. But all I’d thought was: Not to be. It was just as well. I had an early train to catch the next day, and a big, shitty day after that, and I never slept well with strangers.

I hadn’t slept well anyhow, and I’d been up early, so I’d caught an earlier train down to London. And there she was, on that train. It was the third time in twenty-four hours that I’d seen her and when I walked into that train’s café car, I remember feeling a jolt. As if the universe was saying: pay attention.

So I’d paid attention. I’d stopped and we’d chatted, but then we were in London and about to go our separate ways. By that point, the knot of dread that had been building in me since Yael’s request that I return to Holland to sign away my home had solidified into a fist. The banter with Lulu on the way down to London had made it unravel, somehow. But I knew that once I got on that next train to Amsterdam, it would grow, it would take over my insides, and I wouldn’t be able to eat or do anything except nervously roll a coin along my knuckles and focus on the next next—the next train or plane I’d be boarding. The next departure.

But then Lulu started talking about wanting to go to Paris, and I had all this money from the summer’s worth of Guerrilla Will, cash I wouldn’t be needing much longer. And in that train station in London, I’d thought, okay, maybe this was the meant to be: The universe, I knew, loved nothing more than balance, and here was a girl who wanted to go to Paris and here was me who wanted to go anywhere but back to Amsterdam. As soon as I’d suggested we go to Paris together, balance was restored. The dread in my gut disappeared. On the train to Paris, I was as hungry as ever.

On screen, Lulu is crying. I imagine my Lulu waking up the next day, finding me gone, reading a note that promised a quick return that never materialized. I wonder, as I have so many times, how long it took her to think the worst of me when she already had thought the worst of me. On the train from London to Paris, she’d started laughing uncontrollably, because she’d thought I’d left her there. I’d made a joke of it; and of course, it wasn’t true. I wasn’t planning that. But it had got to me because it was my first warning that somehow, this girl saw me in a way I hadn’t intended to be seen.

As the movie goes on, desire and longing and regret and second-guessing of everything about that day start building in me. It’s all pointless, but somehow knowing that only makes it worse, and it builds and builds and has nowhere to go. I shove my hands deeper into my pockets and punch a hole right through.

“Damn!” I say, louder than I mean to.

Lien looks at me, but I pretend to be absorbed in the movie. The piano player is building to a crescendo as Lulu flirts with Jack the Ripper and, lonely and defeated, invites him up to her room. She thinks she has found someone to love, and he thinks that he has found someone to love, and then he sees the knife, and you know what will happen. He’ll just revert to his old ways. I’m sure that’s what she thinks of me, and maybe she’s right to think it. The film ends with a frenzied flourish of the piano. And then there’s silence.

The boys sit there for a minute and then all start talking at once. “That’s it? So he killed her?” Broodje asks.

“It’s Jack the Ripper and he had a knife,” Lien responds. “He wasn’t carving her a Christmas turkey.”

“What a way to go. I’ll give you one thing, it wasn’t boring,” Henk says. “Willem? Hey, Willem, are you there?”

I startle up. “Yeah. What?”

The four of them all look at me for what feels like a while. “Are you okay?” Lien asks at last.

“I’m fine. I’m great!” I smile. It feels unnatural I can almost feel the scar on my face tug like a rubber band. “Let’s go get a drink.”

We all make our way to the crowded café downstairs. I order a round of beers and then a round of jenever for good measure. The boys give me a look, though if it’s for the booze or for paying for it all, I don’t know. They know about my inheritance now, but they still expect the same frugality from me as always.

I drain my shot and then my beer.

“Whoa,” W says, passing me his shot. “No kopstoot for me.”

I knock his shot back, too.

They’re quiet as they look at me. “Are you sure you’re okay?” Broodje asks, strangely hesitant.

“Why wouldn’t I be?” The jenever is doing its job, heating me up and burning away the memories that came alive in the dark.

“Your father died. Your mother left for India,” W says bluntly. “Also, your grandfather died.”

There’s a moment of awkward silence. “Thanks,” I say. “I’d forgotten all about that.” I mean it to come out as a joke, but it just comes out as bitter as the booze that’s burning its way back up my throat.

“Oh, don’t mind him,” Lien says, tweaking his ear affectionately. “He’s working on human emotions like sympathy.”

“I don’t need anyone’s sympathy,” I say. “I’m fine.”

“Okay, it’s just you haven’t really seemed yourself since . . .” Broodje trails off.

“You spend a lot of time alone,” Henk blurts.

“Alone? I’m with you.”

“Exactly,” Broodje says.

There’s another moment of silence. I’m not quite sure what I’m being accused of. Then Lien illuminates.

“From what I understand, you always had a girl around, and now the guys are worried because you’re always alone,” Lien says. She looks at the boys. “Do I have that right?”

Kind of sort of yeah, they all mumble.

“So you’ve been discussing this?” This should be funny, except it’s not.

“We think you’re depressed because you’re not having sex,” W says. Lien smacks him. “What?” he asks. “It’s a viable physiological issue. Sexual activity releases serotonin, which increases feelings of well-being. It’s simple science.”

“No wonder you like me so much,” Lien teases. “All that simple science.”

“Oh, so I’m depressed now?” I try to sound amused but it’s hard to keep that tinge of something else out of my voice. No one will look at me except for Lien. “Is that what you think?” I ask, trying to make a joke of it. “I’m suffering from a clinical case of blue balls?”

“It’s not your balls I think are blue,” she says coolly. “It’s your heart.”

There’s a beat of silence, and then the boys erupt into raucous laughter. “Sorry, schatje,” W says. “But that would be anomalous behavior. You just don’t know him yet. It’s much more likely a serotonin issue.”

“I know what I know,” Lien says.

They all argue over this and I find myself wishing for the anonymity of the road, where you had no past and no future either, just that one moment in time. And if that moment happened to get sticky or uncomfortable, there was always a train departing to the next moment.

“Well, if he does have a broken heart or blue balls, the cure is the same,” Broodje says.

“And what’s that?” Lien asks.

“Getting laid,” Broodje and Henk crow together.

It’s too much. “I’ve gotta piss,” I say, standing up.

In the bathroom, I splash water on my face. I stare in the mirror. The scar is still red and angry, aggravated, as though I’ve been picking at it.

Outside, the corridor is crowded, another film having just let out, not the de Bont but one of those treacly British romantic comedies, the kind that promise an everlasting love in two hours.

“Willem de Ruiter, as I live and breathe.”

I turn around, and coming out of the cinema, her eyes misty with fabricated emotion, is Ana Lucia Aurelanio.

I stop, letting her catch up. We kiss hello. She gestures for her friends, people I recognize from University College, to go on ahead. “You never called me,” she says, adjusting her face into a little girl pout that somehow looks charming on her, though almost anything would.

“I didn’t have your number.” I say. I have no reason to be sheepish, but it’s like a reflex.

“But I gave it to you. In Paris.”

Paris. Lulu. The feelings from the movie start to come back, but I push back against them. Paris was make-believe. No different from the romantic movie Ana Lucia just saw.

Ana Lucia leans in. She smells good, like cinnamon and smoke and perfume.

“Why don’t you give me your number again,” I say, pulling out my phone. “So I can call you later.”

“Why bother?” she says.

I shrug. I’d heard rumors she wasn’t too happy when things ended last time. I put my phone away.

But then she grabs my hand in hers. Mine is cold. Hers is hot. “I mean why bother calling me later when I’m right here, right now?”

And she is. Here now. And so am I.

The cure is the same, I hear Broodje say.

Maybe it is.

Ten

NOVEMBER

Utrecht

Ana Lucia’s dorm is like a cocoon, thick feather quilts, radiators hissing full blast, endless cups of custard-like hot chocolate. For the first few days, I am content just to be here, with her.

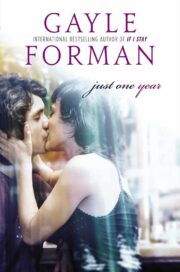

"Just One Year" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Just One Year". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Just One Year" друзьям в соцсетях.