But Hugh could see little through the visor slit, and his eyes were half blinded with sweat. He knew only that here in the moment of victory over de Cheyne there was somehow new battle. And he turned on the Duke.

There was a rumble of astonishment from those spectators who had noticed this particular engagement, whispers of "Lancaster's unhorsed! Who's he fighting? What happened?"

One of the marshals galloped up and then paused uncertainly. By the rules of combat any knight on the one side might singly engage any one of the opponents, but in actual practice nowadays this was unusual, and the two princely leaders were tacitly reserved for each other.

But Blanche knew what was happening. She stood up, marble-still, her eyes fixed on the figures across the lists. And Katherine knew. She had held her breath while she watched the fight between Roger and Hugh, but the spectacle had not seemed very real; it was like the banging, slashing battles the mummers played, and there had been room in her heart for a primitive female thrill, since the two knights fought over her.

But when she saw that the Duke had somehow taken Roger's place her detachment fled and fear rushed in. She gasped at each of Hugh's lunges and tightened as though to receive them on her own body; her lips moved incessantly. "Make him win, Blessed Mother, make him win," and it was the Duke that she meant.

It lasted only three minutes. Hugh's crazy rage did not abate, but he was no match for John of Gaunt, whose cool head, lean, powerful body and chivalrous training from babyhood had made him the most accomplished knight at court. John parried the vicious blows and waited until Hugh's right arm was raised, then he hit the gauntleted hand a tremendous blow. Hugh's sword went spinning down the field.

The Duke with studied deliberation lowered his own sword and thrust it into the ground, while thundering applause shook the loges, and the King, cupping his hands, shouted, "Well done, Lancaster! Well done, fair son!"

It was then that Hugh realised who his opponent was. He staggered backwards, raising his visor. "My Lord Duke, I'm honoured."

John gazed at him with icy eyes. "You're not honoured, Swynford, you're disgraced. Look at your sword-" He pointed with his mailed shoe at the unguarded point of Hugh's sword as it lay in the dust. "And you wounded young de Cheyne in unfair combat."

Hugh turned purple under the sweat-caked dust. "By God, sir, I didn't know. I swear it."

"Get out of the lists," said the Duke. "We'll deal with you later." Hugh turned and limped slowly off the field.

John dismissed the problem of Hugh and, mounting his horse again, accepted the lance from his squire and rested it in the socket, preparatory to running the final course with Lionel. He saw that this course would be the end of the tournament, since the lists were cleared of all but two combatants, a French knight and Sir Michael de la Pole, his own man. He beckoned to the marshal. "How has it gone? What is the tally?" he asked.

"It is a near thing, Your Grace. The Duke of Clarence was ahead until you bested that knight." The marshal indicated Hugh's retreating figure. "But now, I see, his forces are ahead again." For even as they conferred, the French knight dexterously backed Sir Michael against the far stockade, and the Englishman raised his sword-hilt high in token of submission.

"By Christ's blood, then, we must try to even the contest," cried the Duke and he waved his lance in signal to Lionel.

The crowd, which had been restive, quietened and watched with delight as the two resplendent Plantagenets ran the final course against each other. Here was no blind unruly jousting, but an elegant deed of arms with each fine point of technique observed. The ceremonious bowing of the helmeted heads as the herald's trumpet sounded, the simultaneous start from the lines drawn at either end of the lists, the lances held precisely horizontal, the control over the snorting destriers who were always liable to swerve, the shivering impact of the lances square on the opposing shields and the final neat thrust sideways of Lancaster's lance, which dexterously knocked the helmet up and off Lionel's head, where it dangled by the lacings from the gorget.

"Splendid, splendid!" cried the King, proud of his sons.

John and Lionel came riding up to their father's loge and bowed to him while the heralds, once more taking the centre of the field, proclaimed that the great tournament in honour of St. George had ended in a draw. The crowd groaned with disappointment. But, continued the heralds, the prizes would be given anyway by lot tonight at the Feast of the Garter and the special prize for the knight adjudged to have been most worthy in the tournament would also be presented then.

"Lancaster! Lancaster!" yelled a hundred voices, and John flushed. "Lancaster's the worthiest knight!"

It was the first time he had heard himself acclaimed by the mob, and he found it unexpectedly sweet. The King, his father, was immensely popular, of course, and Edward, Prince of Wales, was an idol. Even Lionel, the great blond giant who now sat good-naturedly grinning at his brother, had always, except in Ireland, enjoyed public admiration.

But John was a third son, and the most reserved of all Edward and Philippa's brood. He could inspire deep devotion amongst his intimates, but he had not the gift of easy camaraderie. He knew that most people, and certainly the common folk, thought him haughty and cold. He had been quite indifferent to their opinion, but now at the continuing shouts he felt a pleasant warmth.

He rode over to Blanche's loge and looked up at her smiling. "Well, my dearest lady," he said, "did you enjoy the tournament?" He looked very boyish with his ruddy gold hair tousled by the helmet, streaks of dirt on his cheeks and a happy look in his brilliant blue eyes, which gazed only at Blanche. He had not seen Katherine down on the platform, and he ignored the other admiring ladies around his wife.

"You were wonderful, my lord," said Blanche softly, leaning over the parapet towards him. "Listen how they shout for you. Grand merci to the Blessed Saint John who protected you from harm."

Oh, yes, thought Katherine fervently, gazing at the Duke. A strange pain twisted her heart, and she looked away quickly.

Blanche caught the motion of Katherine's head. "Is young de Cheyne all right?" she asked, leaning closer to her husband whose tired horse now stood quiet next to the parapet. "I couldn't understand just what happened, but Sir Hugh-"

"- is a dangerous fool," snapped John, his face darkening. "I shall deal with him. Though it's that wretched girl's fault."

"Hush, my lord," cried Blanche, glancing swiftly at Katherine. "The poor child's not to blame."

It was then that John saw her sitting below his wife's chair. Her grey eyes with their long shadowing lashes were gazing out over the lists towards the distant oaks. In one quick angry glance he saw the change her new clothes had made in her, the long creamy neck exposed and the velvet flesh in the cleft of her breasts, which were outlined by the tight green bodice. He saw the dimple in her chin and the voluptuous curve of her red lips, he saw the tiny black mole high on her cheek where the rose faded into the gleaming white of her innocent forehead. He saw the rough, reddened little hand, the great beryl ring on the middle finger. She was sensuous, provocative, glowing with colour like a peasant, and it seemed to him an outrage that she should be ensconced here next to his Duchess.

"Apparently you have no interest in the fate of your chevaliers, madamoiselle de Roet," he called in a tone of stinging rebuke.

Fresh dismay washed over Katherine. The unkindness of his voice did not hurt her so much as the stab of her own conscience. For it was true, she had been thinking not of her betrothed or the charming young man to whom at the convent she had given so much thought. She had been immersed in a sudden fog of loneliness, unable to look at the soft expression of the Duke's eyes as they gazed up at his lovely wife. What's the matter with me? she thought, and she turned her head with her own peculiar grace and said quietly, "I am indeed concerned for Sir Hugh and Sir Roger, my lord. How may I best show it?"

John was silenced. The girl's poise showed almost aristocratic breeding, though she came of yeoman stock. And it was true that she could not run down to the leech's tent amongst all the disrobing men and find out for herself. He beckoned to one of his hovering squires, but the young man already had the required information, having just come from the pavilions.

He said that Roger de Cheyne, though faint from loss of blood, would recover, the stars being propitious. The King's leech, Master John Bray, had poulticed the neck wound. Sir Hugh Swynford was uninjured except for a twisted wrist and a bone or two broken in his hand, as a result of the Duke's blow. He had refused the services of the surgeon and gone at once to his tent.

John and all those near enough to hear the squire listened attentively and nodded approval. A gratifying tournament, few casualties and probably no deaths. At least today. Everyone knew that injuries bred fever and putrefaction later, but the outcome would depend on a man's strength, the skill of the physician and his ability to read the astrological aspects aright.

"Farewell, my sweet lady," said the Duke to his Blanche. "I'll see you at the banquet." Ignoring Katherine and the rest of the Duchess's entourage, he trotted his horse off towards the pavilions. It was necessary to punish Hugh in some way for flagrant transgression of the rules, but the heat of John's anger had passed. Poor Swynford was bewitched and doubtless couldn't help his behaviour. Besides, a fierce and vengeful fighter was invaluable in war, however improper at a tourney.

And war was now John's great preoccupation. War with Castile. A deed of arms so chivalrous as to reduce these little jousts and melees to the pale counterfeits they were.

That very morning four knights, Lord Delaware, Sir Neil Loring and the two de Pommiers had arrived at Windsor from Bordeaux bearing official letters from Edward the Prince. There had been no time for the King to digest these letters yet, but John had read them. They contained an impassioned plea from his brother, asking for help in righting a great wrong. All of England must help, all of Christendom should help, in restoring King Pedro to his throne and driving out the odious usurping bastard, Henry Trastamare. King Pedro and his young daughters had been reduced to ignominious flight, and had to throw themselves on Edward's mercy at Bordeaux and beg for help, reminding him most pitifully of England's long-time alliance with Castile. That rightful anointed kings should find themselves in such desperate plight must move every royal heart to valorous response and to arms! That was the gist of the Prince's letters, and certainly John's own heart had responded at once.

He burned to distinguish himself in battle as his elder brothers did. His military role, so far had been unimpressive, through no fault of his own, but he chafed under the memories.

At fifteen he had gone to France with his father, full of hope that he might find glory in another Crecy as his brother Edward had done nine years before. But this French campaign bogged down into a welter of plots and counter-plots. King Jean of France blockaded himself behind the walls of Amiens and would not fight; it was all anticlimax and disappointment. King Edward knighted young John anyway, but there was no glorious deed of arms to give the ceremony savour, and the King, moreover, was preoccupied with trouble in Scotland.

The English returned home in a hurry, prepared to subdue the impudent Scots who had, as usual, seized any opportunity to capture Berwick. John was jubilant again. The Scots would do as well as the French as a means to prove his courage and new knighthood. Again he was disappointed. Berwick, unprepared for a siege, gave up at once, and then the infamous Scottish king, Baliol, surrendered his country to King Edward for two thousand pounds, and the English marched unchecked to Edinburgh, burning and looting as they went.

There was nothing in this moment of Scotland's abasement to thrill a boyish heart, fed on the legends of King Arthur's days, and fretting to prove himself the perfect knight. But in Edinburgh he at least had a glimpse of chivalry. His father, the King, had intended to burn Edinburgh as a final and conclusive punishment for the Scots. But the lovely Countess of Douglas flung herself weeping before the angry conquerors, imploring him to spare the city.

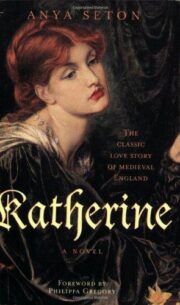

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.