The Duchess, after consultation with Piers, had finally realised something of conditions at Kettlethorpe and done her best to mitigate them.

Katherine had poignantly grateful thoughts on the long ride and made many good resolutions for her future. She would be as much like the Duchess as possible - always gracious, charitable and devout. She doubted her power to force Sir Robert to celebrate daily Mass as did the Duchess' chaplain, but at least she could pray every day and she need not wickedly skip Sunday Mass because of trifling illness, as she had through the autumn. She saw now clearly that she had grown guilty of the sin of accidie - spiritual sloth. The nuns had talked much of that sin at Sheppey.

She had time for conscience - searching, as the ride home took fifteen hours. The lumbering carriage travelled slowly; after they had rested the horses at Lincoln, it began to snow, and the last miles to Kettlethorpe were nearly as wearisome as they had been when she first came there in May with Hugh. And her welcome was scarcely better. The manor house was dark, the servants, not expecting her, had gone to bed in the kitchen loft and when routed out by Piers were surly and unhelpful and scarcely attended to Katherine in their wonder at the great painted carriage and their resentment of the supercilious ducal postilions.

Katherine went up to her dank musty - smelling solar. She did not undress but crept as she was between the clammy sheets. The night candle flickered and blew out in a gust from the east wind through the shutter. The east wind also carried sound from the tower. An intermittent wailing chant, with sometimes a sharper call as of a question. The Lady Nichola talking to her cat, or to the snowflakes, or to some ghostlier figment of her sick mind - what did it matter?

Nothing had changed. Katherine pulled the bearskin around her ears and clenching her teeth prayed violently for resignation.

The winter snows melted in the strengthening sun. Its fight moved southward and now awakened Katherine through the solar window that gave on to the forest, where nesting rooks began their incessant cawing. A film of ice no longer glazed the moat each morning, and as the pastures turned a tender green, the new - born lambs, white as swan's - down, filled the fragrant air with plaintive bleats.

April came in with soft cloudless days, and gentle nightly showers - prime growing weather; and as the danger to the new - sown crops from freezing or floods abated, the grim faces of the serfs grew softer. They sang often in the fields and the dairies and the malthouse; they even smiled at Katherine while they bobbed their heads to her.

The whole manor pulsed with spring, and Katherine spent most of her time outdoors basking on a bench in the courtyard or strolling dreamily through the lanes, listening to the thrushes and blackbirds. She could not walk far now before her back ached and her ankles swelled, but she was no longer sickly or unhappy. She existed from day to day, peacefully expectant as any fecund animal, yet so accustomed now to her burden that she could not remember how it felt to be free.

In Holy Week, a wandering Grey Friar turned up at the manor to beg a night's hospitality for his small shaggy donkey and himself. Katherine was delighted to accommodate him, and all the more so as he brought news. Brother Francis was bound north into the wilds of Yorkshire on a preaching expedition, but he had come from Boston town, near Bolingbroke. He told Katherine that on April 3, eleven days ago, the Duchess Blanche had been safely delivered of a fair, healthy son who had been christened Henry after her father. "All the countryside rejoiced," added the friar. "I thought our bell at Saint Botolph's church would crack from the wild pealings, and the bonfires in our streets set alight two houses."

"Oh I'm glad!" cried Katherine, "so very glad!" Tears came to her eyes, of honest joy for Blanche, but of hurt too. "All the countryside rejoiced" - and yet she had known nothing of it, had worried and prayed for her friend, who might have sent some messenger from amongst her retinue to tell the news. And yet why should she? The Duchess lived in the midst of vast concerns, made vaster now by the birth of a male heir at last; she knew nothing of loneliness or isolation. Doubtless she thought Katherine had heard the news long ago, if she ever thought of her at all. But the hurt persisted.

"This new little Henry of Lancaster," pursued the friar, a small merry man who enjoyed gossiping, "is born to great inheritance, but he has no hope for the English throne, especially since the birth of his new cousin."

"What cousin?" said Katherine, pouring ale for the friar.

"Why, Richard, of course! He that was born at Bordeaux to the Princess of Wales on Epiphany Day." He looked at her quizzically. "Surely, lady, you live here close as the kernel in a nut - most proper though in your state and with your lord away!"

Katherine was nearly stung into telling him that she was not such a country bumpkin as he thought her, that she had visited the Duchess and had stayed at court where her sister waited on the Queen; but the impulse died, for he might think her boastful or lying and, besides, his chatter rippled on without pause.

"When King Edward dies, God give him grace, our glorious Prince of Wales will reign, and after him come his two sons, little Edward - a sickly lad though and given to fits - but now we also have the tiny Richard. If aught should happen to all of them" - he raised his hand and murmured - "Christus prohibeat! - there's the Duke Lionel and his get, present and future, for I hear he's to marry again, and then the Duke of Lancaster and finally our little Henry Bolingbroke, fifth in line if no new ones are born." He shook his head. "Nay, lady, we'll never have a Lincolnshire - born king - a great pity."

"Indeed," said Katherine somewhat dryly. She was growing tired, and her love for Lincolnshire was not such as to make her appreciate this aspect of young Henry's birth. Besides, her heart was still very sore and she desired to hear no more about the Lancasters.

On the last day of April, Katherine awoke early and was filled with restless energy. She dressed and went downstairs to the courtyard before the sun was fairly up. She awakened Toby to make him lower the drawbridge, and walking into the woods, gathered armfuls of flowers and flowering branches. She carried them to the Hall and began to prop them in corners, and in the windy embrasures. Then, seeing that the long oak table was spattered with candle wax and other grease, she called into the kitchen for Milburga.

The maid found her mistress violently polishing the table, and noting the flowers and branches already placed in the Hall, nodded sagely. "Ay lady, I see ye're hands 're restless and ye feel the need for busyness. For sure your time be nigh."

Katherine looked up startled. "Nay, I feel well, better than for long. I but wanted to bring the May into the house ready for tomorrow." Her voice wavered, for she thought of May Day a year ago in London, with Hawise.

"I'll go tell Parson's Molly ye'll be needing her later on," said Milburga stolidly. As usual she managed to convey a subtle contempt for Katherine.

"Nonsense, the baby isn't due yet. Get a rag and help me with this table." Katherine didn't know for sure when the baby was due, but Milburga always aroused, her to opposition.

"Ay, I'd best warn Parson's Molly," repeated the woman as though Katherine had not spoken, "or she might be off at sundown to light the fires and launch Ket's boat on the river."

Katherine bit her lips. Her palm itched to slap the smug sallow face. Milburga well knew that Katherine had forbidden the outlandish ritual performed by her tenants on this St. Walburga's Eve. Gibbon had warned her of it, and described it as a brutish heathen festival which had come down from Druid times and had to do with sacrifice to some dark goddess they called Ket, though some said it was in honour of the Dane, Ketel. No matter which, the proceeding seemed outrageous to Katherine.

The serfs, it seemed, always lit fires in a small circle of ancient stones on a hill near the Trent and after an orgy of dancing, guzzling and worse, they then launched a coracle on the river. The coracle would contain three new - born slaughtered lambs - slaughtered, with wild cries and leapings, on a stone they called an altar. The whole ceremony was called the "Launching of Ket's Ark," Gibbon told her, and his objection to the function sprang not so much from moral indignation at this pagan folderol but from the wanton waste of the lambs and waste of two days' work, one of preparation, and one of recovery from the drinking throughout the night.

But Katherine had been shocked and rushed at once to the priest demanding that he stop the preparations. "Oh, I cannot, lady," said Sir Robert, astonished. "They've always done so here. 'Tis custom. I've often gone myself to launch Ket's ark." "But it's heathen!"

The priest shrugged and looked honestly bewildered.

Then Katherine, calling all her housefolk together and the reeve, had issued a command forbidding them to hold Ket's rite this May Eve. They had said nothing, merely listened to her and dispersed silently. But she had heard the reeve's mocking laugh and Milburga's high - pitched whinny in the courtyard.

"I told you, Milburga, that I forbid this thing tonight," said Katherine, trying to speak with dignity. "I expect to be obeyed."

The maid's lips twitched. "To be sure, lady. So I needn't warn Molly?"

"Certainly not!"

Thus it was that night, an hour after sundown, that Katherine felt her first pains and found herself alone, deserted by all the housefolk. They had fed her her supper, and Katherine, not dreaming that they would defy her and being still in a restless mood, had gone up to the solar and sitting by the window with her lute, strummed random chords while she tried to remember a song she had sung at Bolingbroke.

She took pleasure in her music, and though mostly self - taught, had become a fair player, so that at first she did not notice the growing sharpness of an ache in her back. But the pain grew more insistent, and she stood up, thinking to ease the cramp. Sure enough, it ebbed. She leaned out of the window, gazing idling into the dark forest beyond the moat and thinking of Hugh. She had had no news of him except that given her by the Duchess in January of his arrival overseas, but she had expected none. Even if he had found someone to write a letter for him, whom could he have sent to deliver it? Yet he had hoped to be home in May and perhaps he might be. It seemed to her that if he came she would be neither sorry nor glad, though she would feign gladness.

She sighed, then tensed, holding on to the rough stone of the embrasure and hearing her own startled breathing. The ache in her legs and back had returned more strongly, and this time before ebbing sent a stab of pain up through her loins.

She ran to the door and down the stairs calling "Milburga!" There was no answer; no lights in Hall or empty kitchen, where the embers had been raked under the curfew for the night. She went out into the quiet court and clenched her hands while another pain came and went. "Toby!" she shouted underneath the gatehouse windows. Though the bridge was down the keeper was not there.

She stumbled to Gibbon's hut, and flung the door open.

"God's wounds, what is it?" cried the man's slow voice in the darkness. "Is it you, my lady? Open the shutter." After a moment she obeyed, and he saw her in the gloaming light. She was crouching, her arms laced tight across her belly.

"Jesu - " whispered the sick man. "Poor creature, so your time has come - but lady, go up to bed, send for the midwife. Oh ay - I'd forgot - God blast them all - they've gone to Ket's hill." A spasm twisted his yellow face. "Is no one here?"

"No - one," she gasped, "and I dare not try to reach the village."

" 'Twould do no good, there'd be nobody there. I heard them go - they were laughing, shouting drunken songs." The veins corded on his forehead. "Devil take this stinking useless body of mine - "

"What shall I do, Gibbon?" she asked dully.

"Go to your bed." He spoke briskly to hearten her. "It can't be long before they come back. I'll listen and shout, send someone to you. Be brave for a little while, it won't be long." Though he knew well that last year they had stayed the night through at their wicked rites.

"Ay," she said, "I'll go to bed. That would be best." She could not think for herself, and Gibbon's words brought her relief. "The pains're not so bad," she added, trying to smile. "Not near so dreadful as I'd heard."

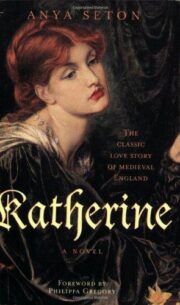

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.