It was unfortunate that amongst the bodies of the Castilian slain they could not find that of the bastard Trastamare, but otherwise the victory had been complete even to the capture of the redoubtable Sir Bertrand du Guesclin. All the victors had held high feast in Burgos, Castile's fair capital. And there, when the messenger from Bolingbroke found him ten days later, John discovered that he had fresh cause for exultation. His son Henry had been born on the same day as the triumph at Najera, surely a most auspicious bit of fortune. He gave thanks in the cathedral and determined to make a quick trip home to see his son - and Blanche. But neither sentiment nor paternal pride alone could justify the time expended on such a voyage, for there were still angry matters to smooth out in Castile and his brother needed him. So John bore letters to the King at Westminster and, more important, had seized the opportunity to replenish his purse from funds held by his receiver - general at the Savoy. The campaign, however glorious, had been expensive.

These matters passed through his mind as he stood by the window and he almost regretted the impulse that he sent him here this morning; for he saw that he could not leave at once as he had planned, while Katherine lay helpless, at the mercy of her serfs and the mad woman Nichola. Yet he was sorely pressed for time and turned plans over in his mind which might best ensure her safety until he could send Hugh back.

He returned to the bed and saw that she had awakened, and was softly kissing the baby's head. "Your villeins must be punished, Katherine," he said, smiling at her. "I understand from your bailiff that you and he forbade their extraordinary rites last night and yet they left you here alone."

"That was my fault, my lord." Through this dreaming bliss she felt no anger towards anyone. "The midwife would have stayed with me but I wouldn't let Milburga fetch her."

The two listening women looked at each other. Molly whispered, "Our little mistress is kind." Milburga shrugged. They held their breaths.

John shook his head impatiently. "These serfs cannot be permitted to defy you - there's no strong arm on this manor, that I see well, nor can I forgive Swynford for leaving you in charge of such a bailiff - a dead man - it was dangerous folly - - " His anger rose at Hugh, though in Castile he had felt none, for Hugh had again proved himself a powerful fighter.

"Poor Gibbon does the best he can," said Katherine softly. "It's I who have been lax."

"Nonsense, child! It's only that you're far too young to have learned the arts of ruling and you must have help. I've decided what shall be done."

"Yes, my lord," said Katherine, humbly. Though he was but twenty - seven he seemed to her the embodiment of unquestioned authority as he stood there, his shining head thrown back, his eyes stern. He spoke to her as her father had used to long ago. There was no tension between them now, nor did she remember that there ever had been. He was but her overlord and her rescuer.

"I shall leave one of my men here to guard you. A Gascon named Nirac de Bayonne and - for a Gascon - trustworthy." John smiled suddenly. Nirac amused him with his quick tongue, nimble wits and sly humour. Nirac was a man of many parts, he could concoct licorice potions or spice hippocras; he could fight with the dagger and sail a ship, the latter accomplishment learned during years of smuggling and freebooting between Bayonne and Cornwall. Though Gascony and the rest of Aquitaine belonged to England, Nirac had not troubled himself about allegiance, until the Prince of Wales' officers caught him and pressed him into military service in the recent Castilian war. And that temporary allegiance would have dissolved as soon as he had been paid, except for the entirely fortuitous circumstances that John had saved his life at Najera.

This was no deed of chivalry - the Duke had simply interposed his well - armoured body between Nirac and a Castilian spear; but the fiery little Gascon had been passionately grateful and attached himself doggedly to the Duke.

John was a shrewd judge of those who served him and he knew that Nirac would obey his commands loyally, and he thought too that of the men with him today, Katherine would be safest with this one. Nirac belonged to that type of man who had but tepid interest in the love of women.

John glanced towards the courtyard window where the sun already slanted above the church spire and said, "Yes - I'll leave you Nirac. He'll keep your churls in order until Swynford gets home. And, Katherine - - "

She looked up at him and waited.

"Your baby must be christened! - now."

Katherine gasped and drew the baby closer. "Is there danger for her? The women said she was unharmed - does there seem something wrong to you?"

"No, no - there's nothing to fear. But we'll christen the babe at once, because I shall be its godfather."

"Oh - my sweet lord," whispered Katherine, flushing with delight. During the vague unreasoning months of her pregnancy she had wondered once or twice who might be found to sponsor the baby if it were actually born.

"It is a very great honour - -" she whispered.

"Yes," said the Duke, "and will help ensure your safety and the babe's." It was for this reason he had suggested it. The spiritual parentage of an infant was no light thing; it linked the sponsor with the real parents in bonds of compaternity, it incurred obligation for the infant's material as well as religious nurture and if, as in this case, the sponsor were of royal blood and the most powerful noble in the land, it endowed the baby with an exalted aura.

A child so honoured on earth and in heaven would be powerfully protected and even Katherine's unruly serfs should be intimidated.

The christening took place an hour later at the old Saxon font in the little church across the lane. The nave was crowded, because the Duke had sent his men to summon all the villagers, many of whom had been shaken and slapped from their drunken snorings. Parson's Molly held the baby and served as godmother since there was obviously no one else in the least suitable on the manor. At the baptismal questions, John took the baby from Molly and made the responses himself, though waiting with barely concealed impatience while the flustered Sir Robert tried to remember the Latin form, could not, and reverted to English.

The baby was christened Blanche Mary as Katherine had asked. And she wailed satisfactorily when the holy water doused her head and the devil flew out of her.

Katherine, lying tense and strained on her bed, heard the glad ringing of the church bell and dissolved into happy tears. My tiny Blanche, she thought, Blanchette, named for the lovely Duchess and the Blessed Queen of Heaven. She would be safe now for ever from the horrors that menaced the un-baptized. And surely all the good fairies had hovered near this christening and brought the baby luck, though there was scarcely need for luck greater than sponsorship by the Duke.

How good he is, she thought, and she felt for him die same gratitude and humble admiration she did for the Lady Blanche, and she felt too that she was purged completely from those other darker feelings towards him which now seemed to her incredible.

When the Duke preceded Molly and the baby back into the solar, Katherine greeted him with a soft little cry and, taking his hand, kissed it in a childlike gesture of homage.

The Duke, receiving it as such, bent over and kissed her quickly on the forehead. "There, Katherine, your babe is now a Christian and you and I have become spiritual brother and sister. So I must leave you. I can scarce reach Bolingbroke tonight as it is."

She nodded. "I know, my lord. I'm sorry. And when you see Hugh - -"

"Ay," he broke in with sudden curtness, "I'll tell him all and send him back. In the meantime, here is Nirac."

The little Gascon had been hovering in the doorway and skipped in at his master's call crying "Oc! oc! seigneur -" followed by a further string of liquid syllables which Katherine could not understand. The man was like a blackbird with his bright round eyes, his cocky strut and a cap of hair like glossy blue - black feathers. He wore the Duke's blue and grey household livery, and the tunic clung like a glove to his spare wiry body.

John laughed and said to Katherine, "Nirac speaks the langue d'oc, but much else as well, some Spanish, the barbarous Basque, French of course."

"And English, seigneur, also - I am a man of many tongues and many talents."

"Daily you prove that Gascon bragging shames even the devil," said John a trifle sternly, "but I'm entrusting you here. You will guard this lady -"

"With my life, seigneur, with my honour, with my soul, I swear by the Virgin of the Pyrenees, by Sant' Iago de Compostela, by the English Saint Thomas, by -"

"Yes, well, that's enough, you little jackanapes. I trust you'll never be forsworn. I've told the serfs that I leave you here in my place until their rightful lord comes home. You'll know how to make them obey?"

The bright beady eyes sobered and gazed intently up at the Duke's face. "Oui, mon duc." He nodded once. "Your wish shall be done in every sing - long as Nirac de Bayonne has breat' in body - -" His narrow brown hand fingered the hilt of his dagger.

"No, said the Duke, glancing at the dagger, "you must be chary of violence. The English have laws on the manor, 'tis not like your wild mountain country. You must be guided by the Lady Katherine."

The Gascon's hand dropped, he looked at the pale girl on the bed, then back into the Duke's face as though reading something there. He ran to the bedside and knelt. "Votre serviteur,belle dame," he said. "I shall guard you for the Duke."

Neither of them gave any deeper meaning to these words or guessed that Nirac had misconstrued the situation. He came of a primitive southern race where emotions were as simple as they were violent. There was love and there was hate, and no nuances between. He loved the Duke; therefore he would love this girl whom he took to be the Duke's leman, else why should his master waste all this time attending to such trivial matters as baptisms and peasants? Perhaps the baby was the Duke's - that would explain matters, and explain too why the young mother never spoke of her husband in the days that followed, but spent all her time nursing and petting her baby.

She listened though, when Nirac spoke of the Duke, while a smile, naif - wistful and half - awed, would light her grey eyes. Nirac, eager to please her, sang often of the Duke's bravery at the battle of Najera. Sir John Chandos' herald had made up a song after the battle, and it began:

En autre part le noble duc

De Lancastre, plein de vertus

Si noblement se combattait

Que chaqu'un s'en emerveillait. . . .

She listened and she took pleasure in Nirac's company. They often spoke French together, he was gay, and of some help to her on the manor by his very presence, though the serfs resented him bitterly. Still, for the next few weeks they gave no further cause for complaint, being thoroughly cowed by the ducal visit. But there were many whispered conferences in the alehouse and on the whole the distrust of Katherine increased, now that she was forever shadowed by this other foreigner whom the terrifying Duke had foisted on them. Singing they were, the lady and that strutting little rooster at all hours in the Hall, in a gibberish no one understood. The manor folk longed for their rightful English lord to return.

Parson's Molly always defended her mistress when she heard the others reviling her. She pointed out how the lady had shown mercy in many ways and particularly in the matter of the Lady Nichola. She had ordered that the crazed woman be unchained and simply confined to her tower - room behind a locked door, and Lady Katherine herself brought up milk and bread and spoke gently to the woman who had tried to steal her baby. But the Lady Nichola never answered, she crouched now day and night in a corner of her room while floating little pieces of straw in a pan of water, nor even cared about her cat. At Lady Katherine's orders, they carried Nichola down to the church during Mass and tied her to the rood screen that the evil spirits might be exorcised, and Lady Katherine saw to it that nobody poked or pinched the mad woman at these times, for the little mistress was clement.

And no woman, Molly said, could be a better mother than the Lady Katherine, that was plain for all to see.

"And what of it?" sniffed Milburga. "The ewes and the sows do as much, and she thrives on it herself - the quean."

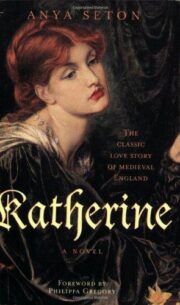

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.