Katherine dropped the bag she carried. She ran stumbling towards the private rooms at the far end of the bailey. She reached the foot of the stone staircase that led up to the Duchess's apartments. Here it was that she had stood laughing at the mummers' antics with the two little girls in that Christmastime three years ago. She looked back into the smoke-filled silent courtyard and saw the hooded figures fumble again beneath the canvas on the mound.

Her stomach heaved, while bitter fluid gushed up into her mouth. She spat it out and, turning, began to mount the worn stone steps. As she rounded the first spiral the hush that held the castle was broken by the sudden tolling of a bell. Muffled though it was by the stone walls around her, she knew it for the great chapel bell and she clung to the embroidered velvet handrail while she counted the slow strokes. Twelve of them before the pause - a child then, this time - somewhere in the castle and dimly through the knell she heard a long far-off wailing.

At once much nearer sounds broke out from above her, a wild cacophony of voices and the shrilling of a bagpipe. She listened amazed; in the discordant sounds she recognised the tune of a ribald song, "Pourquoi me bat mon mart?" that Nirac had taught her, and many voices were bawling it out to the squealing of the pipes and the clashing of cymbals.

As Katherine mounted slowly the noise grew more raucous, for it came from the large anteroom outside the Duchess's solar, and the door was ajar. There were a dozen half-naked people in the room, all of them in frantic motion, dancing. Nobody noticed Katherine, who stood transfixed in the doorway. Despite the fog heat, a fire was blazing on the hearth and the painted wall-hangings were illuminated by a score of candles. On the table, which had been pushed to the wall, there was the carcass of a roast peacock, a haunch of venison and a huge cask of wine with the cock but half shut; a purple stream splashed down on the floor rushes which had been strewn with thyme, lavender and wilting roses. To the falcon-perch beside the fireplace, a human skull had been tied so that it dangled from the eye-sockets and twisted slowly from side to side as though it watched the company who danced around and around upon the rushes. They jerked their arms and kicked their legs. When the minstrel who held the cymbals clashed them together, a man and a woman would grab each other convulsively and, kissing, work their bodies back and forth while the rest jigged and whirled and called out obscene taunts.

Katherine, held viced as in a nightmare, recognised some of these people, though their faces were crimson and slack with drunkenness. There was Dame Pernelle Swyllington, the stout matron who had protested against Katherine's presence in the Lancaster loge at the tournament at Windsor. Her bodice was torn open so that her great breasts hung bare, and the cauls that held her grizzled hair had twisted loose and bumped upon her shoulders as she danced. There was Audrey, the Duchess's tiring-woman, dressed in a wine-stained white velvet gown, trimmed with ermine, the skirt held bunched up around her waist, though yet she tripped and stumbled on it. Her broad peasant face was wild as a bacchante's beneath one of the Duchess's jewelled fillets. Audrey held Pier Roos by the hand and when the cymbals crashed, she flung herself against his chest, slavering. The young squire wore nothing but a shirt and was drunk as the rest, his pleasant freckled face drawn down into a goatish mask, his eyes narrow and glittering. A kitchen scullion danced with them, and a small pretty young woman - a lady, by her dress - who giggled, and hiccuped and let any of the men fumble her who wished; Piers, or the scullion, or the minstrels - or Simon Simeon, the steward of Bolingbroke Castle.

It was the sight of this old man, his long beard tied up with a red ribbon, his portly dignity lost in lewd capers, a garland of twined hollyhocks askew on his bald head, that shocked Katherine from her daze.

"Christ and His Blessed Mother pardon you all," she cried. "Have you gone mad - poor wights?" A sob clotted in her throat, and she sank down on to a littered bench, staring at them woefully.

At first they did not hear her; but the piper paused for breath and the steward, turning to catch up a mazer full of wine, saw her and blinked foolishly, passing his hand before his bleared eyes.

"Sir Steward," she cried out to him, "where is my Lady Blanche?" Her despairing voice shot through them like an arrow. They ceased dancing and drew back, huddling like sheep menaced by sudden danger. Dame Pernelle clenched her hands across her naked breasts and cried thickly, "Who are you, woman? Leave us - begone." Piers' arm dropped from Audrey's waist and he shouted, "But 'tis Lady Swynford - by the devil's tail! I've longed for this! Come dance with me, my pretty one, my burde, my winsome leman-" His nostrils flared on a great lustful breath, he shoved Audrey to one side and would have grabbed at Katherine, but the old steward stepped between and held his shaking arm out for a barrier.

"Where is the Duchess?" repeated Katherine, unheeding of Piers.

"In there," said the steward slowly. He pointed to the solar. "She bade us leave her - while we wait our turn."

"She's dead then," Katherine whispered.

The steward bowed his head and through mumbling lips he said, "We know not."

Katherine jumped from the bench and ran past them to the solar door. They watched her dumbly. Piers drew back against the others. They made no sound as she went through the door but when it closed behind her a woman's voice cried out, "Give me the wine!", the pipes shrilled and the cymbals crashed anew.

In the great solar it was dim and quiet. Two huge candles burned on either side of the vast square bed that was hung with azure satin. The Duchess lay there on white samite pillows. Her eyes were closed, but her body twitched, her breath was like the panting of a dog. Her arms were closed on her chest below a crucifix, the white flesh mottled from the shoulder to the elbow with livid spots. A trickle of black blood oozed from the corner of her mouth and ran on to her outspread golden hair.

As Katherine gazed down, shuddering, the purple lips drew back and murmured, "Water -" The girl poured some into a cup and the Duchess swallowed, then opened her eyes. She did not know the face that bent over her, and she whispered, "Where's Father Anselm? Tell him to come - I haven't long - nay, Father Anselm's dead, he died the first-" Her voice trailed into incoherent muttering.

Katherine knelt on the prie-dieu which stood beside the bed and gazed up at the jewelled figure of the Blessed Virgin in the niche. No fear for herself entered her mind, nor did She pray that the Duchess would recover, for that would be a miracle worked by God alone. She saw that the plague boils had turned inward, and none that vomited blood ever lived. She prayed only that Ellis would bring the monk in time. She prayed while the candles burned down an inch, and the Duchess shivered and moaned, and once cried out. Suddenly Katherine's wits cleared and she saw that she must go back outside the castle to guide the monk since he would be a stranger, nor did Ellis know of the postern gate.

She knew that it was useless to ask help of those in the anteroom. She slipped down the privy stairway that led to the Duke's wardrobe and out on a corner of the battlements, and down to the bailey.

It was dark outside now except for the glare from the plague fire. The hooded black figures had gone and loose earth covered the ditch. Katherine sped through the bailey and out through the postern door. The fog had blown off into a fine rain, yet at first she could see nobody outside the castle walls. Then she heard the whicker of a horse over by the church and she ran there, calling, "Ellis!"

Her squire and a tall Cistercian monk in white had taken shelter from the rain in the church porch, having indeed been unable to find a way into the castle. Katherine wasted no time on Ellis and, giving the monk a murmur of gratitude, seized the edge of his sleeve. Together they hurried back into the castle and up the privy stair to the Duchess's room.

The Duchess still lived. She stirred as Katherine and the white monk came to her bed, and when she saw the cowled head and the crucifix the monk held out to her as he said "Pax vobiscum, my daughter," she gave a long sigh and her hand fluttered towards him. The monk opened his leather case and laid the sacred parts of the viaticum out on the table, then he motioned to Katherine to leave.

The girl crept down the stairs and turned off the landing into the little room called the Duke's garde-robe, because it was in here that he dressed and that his clothes were kept when he was in residence. It was bare now except for two ironbound coffers, a rack full of lances and an outmoded suit of armour that hung from a perch and shone silver-grey in the darkness. A faint odour of lavender and sandalwood clung to the room and there was here no plague stench.

Katherine sat on the coffer with her head in her hands until the monk called out to her.

The Duchess died next morning at the hour of Prime while a copper-red sun tipped above the eastern wolds against a lead sky. Katherine and the Cistercian monk knelt by the bedside whispering the prayers for the dying, and one other was with them - Simon, the old steward of the castle, who had recovered from his drunkenness and crept in to join them, his head bowed with heavy shame.

A little while before her passing, the Lady Blanche's torments eased, and it seemed that she knew them. She tried to speak to the steward and though the words were not clear, they knew she spoke of her dearest lord, John, and of her children; and Simon breathed something of reassurance while the tears ran down his face. Then Blanche's wandering gaze passed over the monk and rested on Katherine with a look of puzzled recognition. She remembered nothing of the night just gone but she felt the girl's love and saw the anguish in her eyes. She raised her hand and touched Katherine's hair. "Christ have mercy on you, dear child," she whispered, while the gracious charm of this most noble lady showed for a moment in her dimming blue eyes. "Pray for me, Katherine - -" she added so faintly that the girl heard with her heart and not her ears.

Then the great room was quiet again except for the chanting of the monk. Lady Blanche sighed, her fingers closed around the crucifix on her breast. "In manus tuas - Domine -" she said clearly, in a calm, contented voice. And died.

It seemed that the Black Death, having slain the Duchess, had at last slaked its greed. The weather on that September 12 turned sharp and freezing cold, and the evil yellow fog vanished. There were a few more deaths throughout the castle, a scullion and a dairymaid, two of the guards and the head falconer's wife; but these had all been stricken before the Duchess died, and there were no new cases.

Of those who had danced in frenzy by the skull in the anteroom, none died of plague but Audrey, the Duchess's tiring-woman, and she followed her mistress on the next day without ever regaining her sense from the drunken stupor which had finally quietened all the revellers.

On Piers Roos, too, the dread black spots appeared, but God showed him mercy, for the plague boil in his groin swelled fast and burst like a rotten plum; and when the poison drained away, Piers recovered, albeit he lay for months in sweating weakness afterwards.

During those days of heavy sorrow and gradually lightening fear, Katherine remained at the castle. They had sore need of help, and old Simon was distracted by the terrible responsibilities on him. Of those at Bolingbroke, thirty had died. Most of the varlets had run off in panic to the wolds and fens. There were few left to do Simon's bidding, and none to tell him what disposition should be made of the Duchess - until the messenger he had dispatched to the King at Windsor should return.

They sealed away the Lady Blanche in a hastily made coffin and placed it in the private chapel. There the good white monk said Masses for her soul, and many of her household came to pray; and there too, every morning after it seemed sure the plague had passed, Katherine brought the ducal daughters, Philippa and Elizabeth, to light candles and kneel by their mother's black velvet bier.

The children had all been safe in the North Tower throughout the scourge; the Holy Blessed Mother had watched out for them, since their own could not.

The baby, Henry, toddled merrily about the floor in his own apartments playing with his silver ball and a set of ivory knights his father had sent him. When Katherine first went to see him he drew back as children do, and hid distrustfully behind his nurse's skirts, but he soon grew used to her and crowed with glee when she played finger games with him as she did with Blanchette.

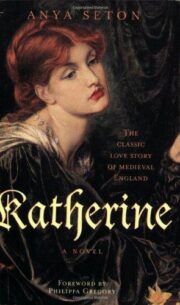

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.