Doucette shied and, while Katherine quieted the mare, she heard a familiar voice raised in sharp protest. "Have care, you clumsy jackanapes! You nearly broke my toe!"

The juggler sheepishly retrieved his anchor, while Katherine leaned over the mare's head and called "Philippa!" and then seeing a tiny figure clutching at the woman's skirts, Katherine jumped off the horse. She scooped Blanchette up in her arms, and rained kisses on the little face that screwed up in protest.

The child started to cry, but as Katherine crooned love words to her, and laughed and held her close, the little pink lips stopped quivering. Blanchette put her arms around her mother's neck.

Philippa had been standing by the fish stall pinching a large glassy-eyed mackerel, while a Kettlethorpe lad teetered behind her with a wicker basket already filled with honeycombs, leeks, stone jars and leather shoes. Philippa flopped the mackerel into the basket, walked up to Katherine and said calmly, "By Sainte Marie, enfin te voila! I've been wondering when you'd get back. Don't start spoiling that child again, the instant you get here."

Katherine set Blanchette down and embraced her sister, seeing that the weeks she had been gone and lived through a lifetime of terror, death, anguish and despairing love, had been placid fast-flying routine for those at home. "And little Tom, Philippa," she said urgently, "is he all right?"

"Of course he's all right. Both babes grown fat and obedient, I've seen to that. Are all these people with you, Katherine?"

She pointed at the three soldiers and recognised Hawise with astonishment. "Why, it's the Pessoner lass!"

Katherine explained briefly that Hawise had come to be her servant for a while and that the Duke of Lancaster had sent escort, at which Philippa nodded with satisfaction, and turned to accompany Katherine and the others up to the castle. Katherine set her delighted little girl upon Doucette, and holding her in the saddle walked beside the mare.

"Hugh is in town today too," Philippa said, puffing hard, for the climb was steep and she had gained much weight now in her sixth month of pregnancy.

"How is Hugh?" asked Katherine quickly.

"Better in health, though grumpy and worried to death over the manor dues. He couldn't pay them at Michaelmas. He can't pay 'em yet. Twice he's been to Canon Bellers in the close to beg for time on Kettlethorpe, and now to the Duke's receiver in the castle about the Coleby rents." Philippa glanced at the men and Hawise, then lowered her voice. "Did you get something substantial from the Duke or Duchess - God rest her soul?"

Katherine shook her head and such a shut, chill expression of warning hardened her beautiful face that Philippa's disgusted expostulation died unspoken. Instead she gave a weary sigh and said after a moment, "Then I don't know what's to be done. Hugh's borrowed all he can from that Lombard in Danesgate. The Duke's receiver, here, John de Stafford, is a mean hard-bitten man who threatens seizure of your lands and chattels." She did not add that she herself had been helping all she could and that the money expended on these market-day purchases had come from her own pension, but Katherine heard the sigh and put her arm around her sister's shoulders. "I'm sorry, rn'amie,", she said sadly. "The sergeant there has some official letter to deliver to this Stafford. Perhaps I should go too and beg him for time."

"It might help," agreed Philippa, sighing again. "I believe he doesn't like Hugh. Bite your lips to make them red, and here" - she patted a coppery tendril of Katherine's blown hair into place.

They had reached the East Gate of the castle walls, and the gate-ward did not even look up as their party streamed through. The castle bailey contained a dozen buildings including the shire house arid the jail, the residence of the constable and the Duchy of Lancaster's offices; and there was a constant coming and going of people on business.

They inquired of a hurrying clerk and walked the horses over to a low building that stood between the ancient Lucy keep and the shire house. The Lancaster coat of arms was nailed above the door, and lolling on a bench beside two tethered horses sat Ellis de Thoresby, Hugh's squire. He greeted Katherine with some warmth, having conceived admiration for her courage in the time of plague at Bolingbroke. Katherine, though she concealed it, was startled at his unkemptness. His shock of greasy hair hung tangled to his shoulders beneath a moth-eaten felt cap. His rusty tunic was threadbare at the elbows and his once yellow hose were profusely patched. Katherine, used now to the sleek elegance of the Lancastrian retinue, was shocked into awareness of their own shabbiness.

Sir Hugh was inside, Ellis told them, had been there for some time, pleading his case with the Lancastrian receiver for Lincolnshire.

"Well, I'm going in too," said Katherine resolutely. The sergeant followed her, holding his letters stiffly in front of him.

One was for Oliver de Barton, the castle's constable, and had something to do with quarters for the sergeant and his men and an exchange of guards, but the content of the other letter to the receiver he did not know.

They walked through a roomful of scribbling clerks who stared at Katherine and made loud smacking noises behind their hands, and across to a door guarded by a page. While the page opened the door to announce them, Katherine heard an angry shouting voice within. "I'll not pay the Coleby rent because I haven't got it yet, and be damned to you! You know bloody well I've not been able to collect from the villeins since the crop failures."

"I know very well, Sir Hugh," interrupted a dry rasping voice, "that your Coleby manor is grossly mismanaged, but 'tis no concern of mine. Mine is to procure your feudal dues to the Duchy of Lancaster, which I shall do - we have several methods -" He turned irritably in his chair. "Well, what is it, what is it?" he said to the page and peered at Katherine and the sergeant in the doorway.

"Hugh," she said, running to him and putting her hand on his arm. She saw startled gladness soften his angry eyes. He made as though to kiss her, then drew back and said awkwardly, "How come you here, Katherine?"

"And who are you that comes here?" Stafford had a small toad-face, with low sloping forehead and unwinking eyes, which regarded Katherine disagreeably.

She said with her most charming smile, "I'm Lady Swynford, sir. I - I cannot think that you'll be too hard on us, for sure a little more time and Sir Hugh will find - -"

"No more time at all," said Stafford, banging his small ink-grimed hand on the table. "Nor does it help your case, Sir Hugh, to drag in a wheedling woman. Tomorrow noon I'll have the rents, that's final. I've been too slack already in my duty to His Grace of Lancaster."

At this the sergeant, who had been listening open-mouthed, cast a look of embarrassed sympathy at the flushed and worried Katherine, and by way of creating a diversion said, "Here, sir, here's a letter to you from His Grace, sent from the Savoy, sir. I've just come from there as escort to my Lady Swynford, sir."

Stafford took the parchment and examined the seal. Many such documents came to him from the chancery and he started to put it aside and dismiss the Swynfords, when he noticed the small privy seal next the large one and frowned. This he had seen but twice before, and it meant that the letter was sent directly from the Duke and sealed with his own signet ring. At the same time, he captured the echo of the sergeant's words,

"escort to my Lady Swynford - from the Savoy - -" He glanced up quickly at the tall girl in the black hood, at the truculent knight whom he thoroughly disliked. A poor tenant, and a poor knight also, since it was well known the Duke had not called him back into service.

Stafford broke the seals and cords on the parchment, read it slowly while a deep mauve tint travelled up his flabby cheeks. He cleared his throat and read it again before saying to Katherine, "Do you know the purport of this order?" She shook her head and her heart beat fast. It was plain that Stafford did not believe her, but he turned to Hugh and said in the tone of one gritting teeth over a hateful duty. "My Lord Duke sees fit to rescue you from your embarrassment, it seems."

He glanced down at the parchment and read the official French aloud in a clipped tight accent. "We, John, Son of the King, Duke of Lancaster, etc., make known that from our especial grace and for the good and loving service which Lady Katherine Swynford, wife of Sir Hugh Swynford, has rendered to our late dearly beloved Duchess, whom God assoil, we do give and grant to the said Lady Swynford until further notice, all issues and profits from our towns of Waddington and Wellingore in the County of Lincoln to be paid at once upon receipt of this letter and thereafter in equal portions at Michaelmas and Easter. In witness, etc., given, etc., at the Savoy this twenty-seventh year of King Edward's reign."

Stafford looked up. The woman seemed astounded, and also as though she were going to weep. The knight looked puzzled and uneasy, obviously straining to understand the unfamiliar French legal words. "What does it mean?" he muttered, biting his lips.

"It means," said Stafford shrugging, "that your wife's revenues from the Duke's towns which he has granted her will pay your rents at Coleby and Kettlethorpe, I should judge, with plenty to spare. That's what it means."

"Huzzah!" cried the sergeant from near the door and met Stafford's glare imperturbably.

Hugh glanced at Katherine and then at the paved floor. "It is most generous of the Duke," he said.

"There's a postscript," said Stafford, tapping the parchment with an irritable finger, "which provides that whenever Sir Hugh Swynford shall be absent from home on knight's service one of the Duke's own stewards shall be appointed to ride to Coleby and Kettlethorpe to render assistance and manor supervision to Lady Swynford, the costs to be met by this office."

Ah, I have been well repaid - thought Katherine, with a bitter pang. The great powerful hand had been bountifully and negligently extended to rescue them. We're only little people, she thought, like the serfs, and what are we but serfs too? She glanced at the grim toad of a receiver. Had chivalry and justice not outweighed the anger that the Duke had felt for her when they parted - there would have been distraint, and punishment. Swynfords would have lost their horses, stock, all chattels - possibly imprisonment too, and the Duke would never have heard of it. But now they were safe.

"Tomorrow at noon," said Stafford, rising, "you will receive the moneys due you from this grant and will then pay your Coleby rent with interest. I give you good day, sir and lady."

The Swynfords walked out through the roomful of clerks and scarcely heeded when the sergeant congratulated them and took his leave to report to the constable. There was no one in the stone passage outside and before going into the court where Philippa and the others waited, Hugh suddenly stopped and looked at Katherine. His hand clenched on his sword hilt, his square face whitened. "For what of your services, my lady, has His Grace of Lancaster seen fit to bestow such reward?" he said, his voice croaking like a rook's.

Her grey eyes met his steadily and with pity, for now she knew what unanswered love was - and jealousy. "For none but what the grant said, Hugh, that I served the Duchess Blanche." She pulled her beads out from her purse and kissed the crucifix. "I swear it by the sweet body of Jesus and by my father's and mother's souls."

His gaze fell first and he sighed. "I cannot doubt you." He leaned towards her. She showed none of her inward shiver as he kissed her hungrily on the lips, but she felt sick fear. Was he then cured of the impotence that had afflicted him? Holy Blessed Mother, she thought, I could not endure it. But she knew she must endure it, if it were so. To escape from his rough grasp she made a business of putting her rosary back in her purse and saw the Duke's letter. "Here," she said quickly, "this is for you, from the Duke. I had forgot in all that trouble in there. Shall I read it to you?"

He nodded, flushing. She broke the seal and scanned the letter. "It's an official order for you to report for knight's duty in Aquitaine. You're to join the company under Sir Robert Knolles, until the - until the Duke arrives himself - ah, that gladdens you!" she cried, for his face had brightened as she had not seen it in years.

"Ay, for I've been ill content to sit at home while others fight, you know that, and I've worried much that the Duke did not want me; it seemed a slight, a punishment, for what I know not. Yet I've but a slow mind and can't follow his."

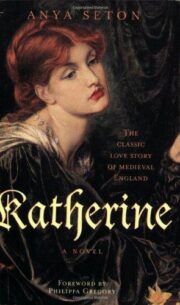

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.