It seemed that Bishop Courtenay himself had finally appeared and berated the mob leaders, saying that they had carried their disorders too far and that he was ashamed of his flock. So one by one they had slunk off to their homes, contenting themselves with reversing the Duke's coat of arms wherever it hung outside a shop and then pelting the blazons with mud and excrement.

"And I'm glad enough now, no harm came to the Duke," said Guy, donning his leather apron which was plastered with fish scales, " 'Twas a good night's work as 'tis, in especial that we let loose the wrongfully held prisoner from Percy's Inn. The marshal'll not try those tricks again."

"What prisoner was that?" asked Dame Emma, coaxingly pushing a dish of fried eggs towards the silent Katherine.

"Some fellow from Norwich. I didna see him. 'Twas said he was in mortal fear o' the Duke. Th' instant he was freed, he hared it off for sanctuary in St. Paul's."

Dame Emma sighed. "And think ye, chucklehead, that this is the end o' London's trouble? Can ye get it through your numskull that violence but breeds violence? D'ye think the Duke will smile and thank ye for this night's work?"

The fishmonger thrust his lip out and said stubbornly, "He should not a tampered wi' our liberties, he should not a set hisself against the Commons."

The goodwife sighed again. "Ay, Commons've no friend at court these days." She bustled over to pat Katherine's shoulder. "Ye don't eat, my lady?"

"No," said Katherine rising, "forgive me but I can't. I must get to the Savoy. God be thanked the Lady Philippa and Hawise seem to've suffered no harm. I had forgot them last night."

Ay, poor lass, you forgot all else but one man's danger, Emma thought as she said, "Ye canna go alone. Go wi' her, Guy, she'll be safe wi' you."

The fishmonger grumbled that a load of herring awaited him at the wharf, that his prentices must be chivvied to work, that there was a mess of cod to be delivered to the Guildhall, but finally he took off his apron and mounted Katherine behind him on his great bay gelding. He was a good-hearted man, and he admired Katherine's fair face, but he was increasingly convinced that Hawise's devotion to this woman was unfortunate, even dangerous. The mortal hatred aimed at the Duke might well glance off and hit those near him, as indeed it already had; and though no coward, Guy did not like certain remarks he had heard last night which reflected on his own connection with the Duke through that of his obstinate daughter.

He rode along in gloomy silence until they had crossed the Fleet bridge, then he said, "How long d'ye look to be down here, m'lady?" For he thought that since Hawise could not legally be forced to break her service indenture to Lady Swynford, and would not if she could, at least the farther away they went, the better.

"Not long," said Katherine with a cold vehemence that astonished the fishmonger. "I shall see to that, Master Guy."

"To Kenilworth, then, or Leicester?"

"No," she said, "to Lincolnshire, to my own home."

"By Saints Simon and Jude!" Guy twisted his fat neck around to stare at her. "Will the Duke allow it? Are ye not contracted to him as governess to his little ladies, as well as by other - other ties?"

"I believe the Duke will not hold me," she said, sitting stiff and straight on the pillion. "And by the Blessed Virgin, I am no serf, to be bound against my will!"

"Well-a-day!" cried Guy, thinking that the riot had very properly frightened her into caution. " 'Tis a sensible plan."

Katherine did not answer.

The gelding jogged along the Strand past St. Clement's little church. Katherine had passed the church fifty times without special notice; today as she glanced at it, eleven years slid away. She saw in the porch a priest and a knight with crinkled hair, and a girl with a wreath of garden flowers on her head. Handfasted, they stood, the girl and the knight, while the priest intoned, "To have and to hold from this day forward to love... and to cherish... till death..."

She turned away from the church and stared down the Strand ahead, then Master Guy started and cried, "By God, see what they did here!"

Katherine looked up at the gatehouse. They had wrenched off the Duke's great five-foot painted shield and hammered it back again upside down.

"'Tis what they do to traitors!" said Master Guy and chuckled suddenly. "Them leopards look mortal silly a-standing on their little heads a-waving their little legs." His chuckles grew into a rumble.

"For the love of Christ - stop it!" Katherine cried, shaking his arm. "Can't you see what you're doing to him? What man could stand the vile lies - the hatred - you know he's not a traitor. Oh, God curse the lot of you!" She jumped down off the horse.

That afternoon, unable to come to rest anywhere, Katherine went out into the Savoy gardens. It was chilly, the clipped yew hedges and the shrouded rosebushes were drenched in grey mist, but she had flung a warm squirrel-lined cloak over the grey woolsey. Nor would she have felt the cold in any case, while she paced the deserted brick paths and thought of her new-found decision.

She would leave here tomorrow. She and Hawise and the Kenilworth servants who had come down with them would return there at once. She would pick up her children and hasten to Lincolnshire - to Kettlethorpe.

John might be momentarily annoyed at her taking their two babies from the luxury of Kenilworth, but since they obviously no longer interested him any more than she did herself, his protest would be a formality. He should have no cause to reproach her for negligence in her duties to Philippa and Elizabeth either. Until he should appoint a new governess, Lady Dacre here at the Savoy would be delighted to wait upon Philippa - and delighted to get rid of me, Katherine thought. Well she knew that most of the ladies treated her with contempt when the Duke was not around. Secure in his love and protection she had always ignored these slights.

Now this was changed.

Back and forth she walked between the frosty yews and thought harsh practical thoughts. She would keep the wardships and annuity he had already given her if he allowed her to, for she owed it to his children, that Kettlethorpe might be made habitable for them. But she needed nothing more. She would be invulnerable again and alone, .with this wicked unwanted love walled out of her heart.

Suddenly she looked down at the ring he had put on her finger in the ruined chapel in the Pyrenees. Betrothal ring. She stared at the round translucent sapphire, the stone of constancy.

Her lips tightened as she twisted the ring from her finger and walked to the river-bank. She stood on the marble pier and holding the ring outstretched in her hand, gazed down at the lapping waters.

"Nay - I cannot," she said, after a moment, turning from the river. She slipped the ring into her scarlet purse that was embroidered with her arms, Swynford boars impaling the Catherine wheels; the blazon he had made for her.

Am I then nothing of myself? she thought with anguish. Can I not live apart from memories of him - -

She sank down on a stone bench, and stared out across the river to the barren stony hummocks of Lambethmoor. The mists grew thicker and downstream the pale lemon light faded over London. One by one from its churches the bells rang out for vespers; near at hand the Savoy chapel gave forth its sprinkle of silvery chimes. She stirred restlessly on the bench.

The bells drowned out the sound of approaching oars on the river until a barge appeared out of the mists quite near the pier. Katherine started for the steps, unwilling to be gaped at, when an eager voice called out, "My Lady Swynford, is it you?"

She turned and recognised Robin's feathered cap and rusty tunic as the squire waved from the barge's prow. She came down the steps and waited while the oarsmen steered up to the pier. "So you've returned," she said quietly. "Your errand last night, Robin, was well done, I've heard."

The youth jumped to the pier and cried, "I've been sent for you, my lady, to come to Kennington. You're to come back with me at once!"

"No - -" said Katherine, unsmiling. In the shadow of her hood her face gleamed hard as pearl, her eyes were cooler than the mists.

Robin was dismayed that the lovely laughing girl who had been his most precious charge was transformed into a stern woman with a stranger's eyes. He stammered, "But, my lady - 'tis a command - you are summoned to Kennington Palace."

" 'Tis kind of His Grace," she said. "You may tell him that I know he has never been lacking in courtesy when he thinks there's cause for it, but in sending you to warn him I did nothing that his lowliest varlet would not have done."

Robin blinked, and looking down at the toe of his leather shoe, said unhappily, "It is not His Grace who summons you."

The bells ceased their ringing and there was silence on the pier. "Who does then?" said Katherine.

"The Princess Joan, my lady - she commands in the name of Prince Richard that you shall come at once."

"Whyfor?" said Katherine, in a less sure tone. "I've never met the Princess, what could she want of me? Robin, is His Grace not at Kennington too?"

"Ay - he was - locked in a chamber with Percy, I believe. I've not seen him since we crossed the river last night. Lady dear - I beg of you to hurry, the Princess was most anxious."

Since there was now no queen in England, Princess Joan was sovereign lady and must be obeyed. Katherine reluctantly let Robin help her into the waiting barge. The oarsmen bent their backs and pulling sturdily against the current moved their craft upstream. They passed Westminster and crossing to the Lambeth bank landed at the Kennington pier.

They went up a terraced path to the fair small country palace where the Prince of Wales had died. Robin led the way through a courtyard and upstairs to the Princess Joan's bower, where a waiting-woman admitted Katherine at once, then left her alone.

The room was gaudy as a jewel box; the walls hung with painted silks, the floor covered with bright woven flowers in a Persian carpet. The furniture was gilded, and in a gold cage studded with crystals two white birds twittered.

As Katherine looked at the birds the Princess entered hurriedly, in a rush of pink velvet and a wave of heavy scent, crying with warm impetuosity, "Welcome, Lady Swynford, I've been awaiting you!" She held out a fat dimpled hand so loaded with diamonds that Katherine, as she curtsied, could scarce find space to kiss.

"I have come, madam, as you commanded," said Katherine distantly, and rising, she waited.

"Take off your mantle and sit down, my dear," said the Princess, while she settled her billowing hips into a canopied chair. Katherine obeyed, wondering what was wanted of her, and her pride hardened still further, for she thought that she could guess.

The Princess was like a large blowzy rose. Katherine noted the dyed hair, the excessive plumpness of the rouged cheeks, the charcoal blackening the scanty lashes, and thought how the nuns of Sheppey Convent had admired this fair maid of Kent, and of how she had once heard a knight say that when Joan had married the Prince of Wales she was "la plus belle femme d'Angleterre - et la plus amoureuse."

Perhaps his brother thought so still.

The Princess cleared her throat and leaning forward said, "My dear, you're not at all as I expected. I see now why - yes - I'm glad I summoned you." The girl looked high-born and well-bred, Joan thought in surprise, with most lovely features. The firm cleft chin showed character too. She was relieved at this new view of Lancaster's mistress, for gossip had it that the little Swynford was an upstart strumpet, and some said that she kept him from the Duchess by the use of black arts.

Joan smiled, the gay confiding smile which had won many a heart, and said, "I have something to ask of you, Lady Swynford - 'tis a delicate matter."

"Perhaps I may save you embarrassment, madam, by telling you that I intend to leave the Duke's service tomorrow, and shall go to live permanently in my own manor in Lincolnshire," said Katherine. "Is that far enough away?"

The Princess' eyes grew round as turquoise discs. "Blessed Saint Mary!" she cried. "Did you think I asked you here to beg you to give up the Duke? Great heaven, child, it is quite the opposite!"

"What!" cried Katherine sharply. "Madam, you are jesting." For the Princess was laughing in small muffled spurts.

"Nay, listen," said Joan wiping her eyes on her pink velvet sleeve. "Forgive me, I don't know whether I laugh or weep, for I am frightened - -frightened - don't stare at me with those great angry eyes - my dear, I need your help." The Princess rose and walking to Katherine cupped the girl's chin in her hand and gazed down earnestly. "Do you really love my brother of Lancaster?" Katherine looked away, and her colour rose. "Ay, I see you do."

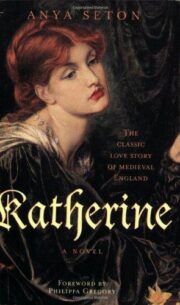

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.