"God's wounds," whispered the Duke. Discouragement dragged him down like a millstone tied to his feet. "I cannot do battle with an undergrown boy of sixteen," he said wearily, pulling on Morel's bridle and turning the horse.

De la Pole glanced at his Duke with sharp sympathy. It must be writ in his stars, thought the baron, naught else could explain the checks and bitter disappointments that constantly assailed poor Lancaster.

But young Percy would not leave it so. He furiously spurred his horse and galloped up the Duke. "But I will fight, I will!" he shouted. "I demand my right to do battle in my father's stead. 'Tis the law of chivalry."

"And what do Percys know of chivalry, young cockerel?" said Lord Neville with a contemptuous laugh.

"Ay, but he has the right," said the Duke slowly, reining in his horse. He shrugged beneath his steel epaulettes. "Be it so. To your end of the field, Percy - -"

Lancaster and Northumberland heralds ran out to the open space and blowing on their trumpets announced the contest. The Duke waited listlessly until he saw the white batons raised and dropped, heard the heralds call "Laissez-aller - -!"

With lances braced and horizontal the two horses pounded down the field from opposite directions. As they crossed each other the Duke negligently parried the boy's wild thrust and on this first course forbore to take advantage of Hotspur's unguarded left flank. But on the second course he shattered the boy's spear and, though his own lance point was broken off by the shock, he swerved Morel and, coolly slanting the butt of his lance into the boy's armpit-beneath the breastplate, lifted him from the saddle and deposited him on the ground.

A wild cheer went up from the Duke's men, but John raised his visor and shook his head frowning. "Have done!" he cried sternly. "There's naught to cheer in this shameful contest."

He dismounted and walked over to Hotspur, whose squire was unbuckling his helmet. When it was off, the boyish face was seen to be wet with angry tears.

"You acquitted yourself bravely, young Percy," said the Duke. "You may tell your father so. Now get back to him, and tell him too that since he skulks and runs from me here I shall certainly confront him later in the presence of the King - unless of course some apt malady of limb should prevent the earl from travelling!"

Hotspur screamed out a trembling defiance, but John turned on his heel and did not listen. He strode back to his tent, while Percy's disgruntled men rode silently away beside their little chieftain.

The Duke and his meinie started south that night and on the sixteenth of July they reached Newcastle-upon-Tyne. A fair prosperous town was Newcastle, albeit a smoky one, for folk here burned the coals they laboriously dug from the surrounding hillsides. The Duke rode at the head of his men to the old Norman Castle that overlooked the Tyne. He entered by the Black Gate and pausing in his chamber in the keep only long enough to remove his armour and cleanse himself, walked down the twisting stone stairs to the beautiful little chapel.

Here he lit a candle to the Virgin and knelt down to pray, hoping as he had each day since Berwick to lift thereby the oppression in his heart. He would whisper the Ave over and over like an incantation and often found comfort in it, but the painted wooden features of this Virgin had in them something of Katherine in the demure lowered lids, the faintly cleft chin, the high rounded forehead, and he turned away from Her in sharp pain.

There was no image of St. Catherine in this chapel so he could not properly renew the vow he had already made, but he repeated it at the end of his prayers. "If I find my Katrine safe and unharmed, I vow to build a chapel to Saint Catherine on any place in my lands that the Blessed Saint shall designate." He kissed the crucifix on his beads and rose.

He went restlessly upstairs to the Hall, where his knights had gathered, some drinking, some dicing, while de la Pole and Neville were engaged in an acrimonious game of chess. The Hall was fetid and smoky from the old-fashioned fire over which the varlets were roasting a bullock; John, glancing in, changed his mind and continued up the stairs to the leaded roof of the keep. The watch, a burly man-at-arms with pike and longbow, was circling it slowly, but John dismissed him. He wanted to be alone.

He leaned his elbows on the parapet in one of the square towers, breathed deeply of the fresh summer air and let his disconsolate gaze wander from the golden furze-covered moors to the north, to the shipping below in the harbour, and on down the pewter-coloured ribbon of the Tyne as it wound into distance towards the sea. He turned slowly to the west where he could see the straight grassy ditch, the mounds and scattered stones of the Roman wall, and he thought of the ages that had streamed by since it was built, and wondered with drear melancholy what had become of the men who built it. Where were their plans and hopes now, what difference had their joys or sufferings made to England? He thought of those of his own blood who had gazed at this ancient wall, his father - all the Plantagenets, and far back to the days of King Arthur himself. In Arthur's reign there had been love-longing and wanhope too and there had been evil to be conquered. But the old tales told of glorious battle against these evils, for there were dragons and giants to be fought in those days, not creeping little jealousies and darting slanders that scurried like spiders into cover when one tried to confront them. He thought with great bitterness of the humiliating, ludicrous outcome of his challenge to Percy, and there rose in him a loathing of Fate that constantly blocked him and denied his deepest wishes.

The sun turned red as blood above the Roman wall and sank down towards the wild desolate moors behind, leaving a sudden chill that struck through John. He turned away and looked down into the castle ward, where his eye was caught by something familiar in a figure that was mounting the long flight of outstairs into the keep beneath. He leaned over the parapet and stared again, then shouted in amazement, "Ho there! You in the brown hood and cloak, look up!"

The man paused on a step, stared around to find the voice until finally, raising his head, he saw the Duke and waved. It was indeed Geoffrey Chaucer, and John's heart beat faster. "Come up here to me!" he called. Geoffrey nodded and disappeared into the keep, and presently came out on to the tiles through a tower door.

The Duke's hand trembled as he held it out: Geoffrey kissed it while he bent his knee, saying with a faint smile, "Your Grace, I've been a long time a-finding you."

"Indeed?" said John, afraid now to ask the question that beat against his lips.

"Ay, my lord. A fortnight ago when you were - ah - detained in Scotland I tried to pass into Northumberland, but was turned back. I waited at Knaresborough until word came that you were at last on your way south."

"Knaresborough," John repeated, and could not hide his bitter disappointment. "To be sure," he said dully. "Your wife is there, I suppose, in the Duchess' train."

"She is, and I've spent some time with Philippa, but 'twas not for that I came north. My lord," said Geoffrey slowly, touching the pouch that hung from his waist, "I bring you a letter from Lady Katherine."

The Duke's indrawn breath was sharp as tearing silk. He grabbed Geoffrey by the shoulders. "She's well then? And unharmed?"

Geoffrey nodded, but looked away because he could not bear the leap of joy and sudden glistening in the blue eyes.

"Thank God!" the Duke whispered. "Thank God! Thank God and the Blessed Saint Catherine!" He seized Geoffrey's hand, "Oh, Chaucer, you shall be well rewarded for this news. Name what you like. Never did I know how dear she was to me till these last days. In fear and suffering I've longed for her - longed-" He broke off. "And where is she now?"

"I don't know, my lord," said Geoffrey, looking down at the leaded tiles. He unbuckled his pouch and drew out a folded parchment. "You would better be alone when you read this," he said quickly. "I'll wait in the little wall chamber in case you should want me."

The happy flush died on the Duke's lean cheeks as Geoffrey disappeared into the tower. He broke the seal on Katherine's letter and read it by the light of the dying sun.

Geoffrey waited in the wall chamber until Newcastle's bells rang out for curfew and the sky through the arrow-slit window showed amethyst. He heard his name called at last and went back up to the tiles.

In the evening light the Duke's face now loomed white as ashes, his voice was thick and halting as he said, "Do you know what's in this letter?"

"Ay, my lord. But no one else does, nor ever shall."

"She cannot mean to give me up like this. She cannot! I don't believe it. She says farewell - that we must never meet again. This coldness, these incredible commands! She who was so warm and soft, who has lain so often in my arms, who has borne my children!" The hollow voice faltered, after a moment went on with a sharper edge. "She speaks of Blanchette. You'd think she had no child but Blanchette!"

"'Tis I think, my lord," Geoffrey ventured, "because of the terror she feels for the little maid, who may be dead. She has not forgot her other children, but they are in no need."

"I am in need," cried the Duke. "She thinks not of that!"

Geoffrey, profoundly disliking this whole coil and his unwilling part in it, yet forced himself to go on. "It is because she loves you that she must give you up. Brother William told her this before he was killed. She believes it. And I, my lord, have come to believe it too. The load of sin, and now the knowledge of murder done would crush you both in the end."

John turned away from Geoffrey and looked out over the parapet into the night of shadows. So it was Swynford's murder that the martyred Grey Friar had meant in all those strange allusions through the years. Nirac, poor little rat - a monstrous sneaking crime in truth - poison - the coward weapon. Sickening. And yet - so long ago, and Nirac had been shriven of his crime by the Grey Friar. The little Gascon's soul was not imperilled. It was Katherine's and his souls that were in danger - so Katherine believed.

"By God," he said roughly, crumpling up her letter, "if fate wills it that we are to be damned, then we shall be damned. I'll not give Katherine up. Where is she, Chaucer?"

"Gone on pilgrimage, my lord."

"Ay - but to where?"

"I don't know, upon my honour. She would not tell. She doesn't wish you to find her."

"Then God help me, she may have set out for Rome - for Jerusalem even!"

Geoffrey was silent. He thought it possible that Katherine had set forth on the longest and harshest pilgrimage of all. He cleared his throat unhappily, for he had not yet discharged all of Katherine's anguished message. "Your Grace - one more thing she bade me tell you. It is not in the letter because she could not bring herself to write it." He stopped, remembering how her control had broken down at last after she had given him the letter to the Duke, how she had covered her face while the tears coursed down between her fingers.

"What is that one more thing?" said the Duke's voice from the shadows.

"She prays you, my lord - by the love you have borne her - to - to ask the Duchess to forgive her. Yes - I know, my lord," said Chaucer quickly as he heard a sharp exclamation, "but this is what she said. Matters have gone badly with you for a long time, and that is the earthly punishment for murder and adultery. The murder cannot be undone but the adultery must cease. She says that you both have wronged the Duchess - who she thinks loves you in her fashion, as truly as Hugh Swynford was wronged who loved Katherine too - as best he could."

"Blessed Jesu! Now I know you lie! Before God, Chaucer, 'tis not for naught you are a spinner of tales!"

Geoffrey stepped back quickly, the Duke had turned on him as though he would strike.

"I've not invented her letter, my lord," Geoffrey cried.

"Her letter!" The Duke's voice shook with fury, he crushed the parchment between his hands and flung the ball violently away from him over the parapet. "That I should live to see Katherine treat me like this! Dismiss me like a thieving scullion, with rantings about morality! She dares send you to prate of love that Swynford bore her! By God, 'tis late times to think of that. What has she been doing there in the south when I thought her tending to her child? She found some pretty youth like Robin Beyvill maybe to while the time away. 'Tis because of him she can turn me off so lightly!"

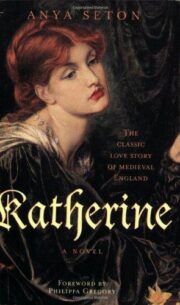

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.