He turned his back on Katherine and said to Blanche, "I'll see you later, lady." He touched his little daughters' curls and strode out of the room, banging the heavy oak door behind him.

"My lord is hasty sometimes," said Blanche, noting the girl's dismay. "And he has grave matters to worry him." She was well used to John's impulsive acts, as to his occasional dark moods, and knew how to temper them, or bide her time until they passed. She hastened now to minister to the unhappy maiden he had brought her and motioned to Audrey to bring the basin and a towel Then she lifted the torn strip of violet cloth and the strands of hair from Katherine's shoulder and found rows of tiny bleeding cuts on the breast beneath. "Tell me about it, my dear," she said quietly, bathing the cuts and salving them with marigold balm.

Hugh sat in his tent on the field near the lists while Ellis his squire removed his armour, but Hugh was unaware of Ellis or his surroundings. His blood ran thick as hot lead in his veins and he suffered desire, shame, and confused torment that nothing in his life had prepared him for.

Hugh Swynford was of pure Saxon blood except for one Danish ancestor, the fierce invading Ketel who sailed up the Trent in 870, pillaging and ravishing as he went. A Swynford girl was amongst those ravished, but she must have inspired some affection in her Dane since she lured him from his thorpe in Lincolnshire to her own home at the swine's ford in southern Leicestershire, where he settled for some years and adopted her family's name.

The Swynfords were all fighters. Hugh's forefathers had resisted the Norman invasion until the grown males of their clan had been exterminated and even now, three hundred years later, Hugh stubbornly rejected any tinge of Norman graces or romanticism. He went to Mass occasionally as a matter of course, but at heart he was pagan as the savages who had once danced around Beltane's fire on May Night, who worshipped the ancient oaks and painted themselves with blue woad - a plant indeed which still grew on Hugh's manor in Lincolnshire.

He was an ungraceful knight, impatient of chivalric rules, but in real battle he was a shrewd and terrifying fighter.

Hugh's branch of the Swynford family had long ago left Leicestershire and returned to Lincolnshire beside the river Trent south of Gainsborough; and when Hugh was a child, his father, Sir Thomas, had fulfilled a long-time ambition and bought the manor of Kettlethorpe where Ketel the Dane had first settled. For this purchase he used proceeds from the sale of his second wife Nichola's estates in Bedfordshire, at which the poor lady wept and lamented woefully, for she was afraid of the towering forests around Kettlethorpe, and of the marshes and the great river Trent with its stealthy death-dealing floods. The Lady Nichola was also afraid of the dark stone manor house, which was said to be haunted by a demon dog, the pooka hound. Most of all she was afraid of her husband who beat her cruelly and constantly reproached her for her barrenness. So her wailings and laments were done in secret.

Hugh thought little about Kettlethorpe one way or the other, beyond accepting it as his home and heritage, and he was a restless youth. At fifteen he struck out into the world. He joined the army under the King, when Edward invaded Scotland, and there met John of Gaunt, who was then only the Earl of Richmond. The two boys were of the same age and Hugh conceived for the young Prince, whose charm and elegance of manner were so unlike his own, a grudging admiration.

At sixteen, Hugh, thirsting for more battle, had fought under the Prince of Wales at Poitiers. Hugh had killed four Frenchmen with his battle-axe, and shared later in the hysterical rejoicing at the capture of King Jean of France.

Hugh won his spurs after that and returned to Kettlethorpe to find that his father had suffered an apoplectic stroke in his absence. Hugh stayed home until Sir Thomas finally died and Hugh became lord of the manor. But as soon as his father had been laid in a granite tomb near the altar of the little Church of SS. Peter and Paul at Kettlethorpe, Hugh made new plans for departure.

He detested his stepmother the Lady Nichola, whom he considered a whining rag of a woman overgiven to fits and the seeing of melancholy visions, so he left her and his lands in charge of a bailiff. He fitted himself out with his father's best armour and favourite stallion, then engaged as squire young Ellis de Thoresby, the son of a neighbouring knight from Nottinghamshire across the Trent.

Thus properly accoutred, Hugh rode down to London, to the Savoy Palace. He owed knight's service to the Duke of Lancaster by reason of Hugh's manor at Coleby, which belonged to the Duke's honour of Richmond, but he had not the money for the fee, and in any case much preferred to become the Duke's retainer, well pleased that his feudal lord should also be the youth he had campaigned with in Scotland.

Though the intervening years had made many changes in John of Gaunt's personal life, for he had married the Lady Blanche and thereby become the wealthiest man in the land, Hugh's own interests remained unchanged. He fought when there was war, and when there was not he pursued various private quarrels, and hunted. Hawking bored him with its elaborate ritual of falconry, for he liked direct combat and a dangerous opponent. The wild stag and the wild boar were the quarries he liked best to pursue through the dense forests. He was skilled at throwing the spear and could handle the longbow as well as any of the King's yeomen, but in close fighting he was supreme.

It was said of him that he had strangled a wolf with his bare hands in the wilds of Yorkshire, and that it was the wolf's fangs which had laid open his cheek and puckered it into the jagged scar, but nobody knew for certain. The Duke's retinue now numbered over two hundred barons, knights and squires, and a man so morose and uncourtly as Hugh excited little curiosity amongst his fellows. They disliked him and let him alone.

But when his extraordinary wish to marry the little de Roet became known, he inspired universal interest at last.

Katherine's frantic protests and tears were of no avail against Hugh's determination and everyone else's insistence that she had stumbled into unbelievable luck.

The Queen's ladies said it, even Alice Perrers said it, and Philippa scolded morning, noon and night.

"God's nails, you little dolt," Philippa cried, "you should be down on your knees thanking the Blessed Virgin and Saint Catherine, instead of mewling and cowering like a frightened rabbit. My God, you'll be Lady Katherine with your own manor and serfs, and a husband who seems to dote on you as well!"

"I can't, I can't. I loathe him," Katherine wailed.

"Fiddle-faddle!" snapped Philippa, whose natural envy increased her anger. "You'll get over it. Besides he won't be around to bother you much. He'll soon be off with the Duke fighting in Castile."

This was pale comfort but there was little Katherine could do except plead illness, hide in the solar and avoid seeing Hugh.

The Lady Blanche on hearing of the girl's aversion to the marriage had broached the matter to her husband and found him unexpectedly obdurate and impatient. "Of course Swynford's a fool to take her. I believe he could have had that Torksey heiress whose lands adjoin his, but I think he is bewitched. Since he lusts so for her, let him have the silly burde."

"You dislike her?" Blanche was puzzled by his vehemence. "I find her quite charming. I remember her father, a gallant soldier. When I was a child he once brought me a little carved box from Bruges."

"I don't dislike the girl. Why should I? I dislike wasting time or thought on such a trivial matter when we're going to war. And the sooner they marry the better, since Swynford will sail for Aquitaine this summer. He might as well beget an heir before he goes."

Blanche nodded. She was no more sentimental about marriage than anyone else, but she was sorry for Katherine and sent a page over with a generous present to help alleviate the girl's unhappiness.

Katherine was alone now because it was the day of the final tournament, and everyone in the castle except the sick Queen and the scullions had gone down to the lists. Though the ladies had urged her and Philippa had commanded, Katherine, who three days ago had so joyously looked forward to this spectacle, would not go.

She was fifteen and incapable of self-analysis. She knew only that this gorgeous new world, at first so entrancing, had resolved itself into a chaotic mass of helplessness and fears, against which she struggled blindly, finding no weapon but evasion. She was much frightened of meeting Hugh again, but vaguely she knew too that this unhappiness was reinforced by a more subtle one. She longed to see the Duke, and this longing upset her as much as Hugh's obsession, for the Duke had not been her champion after all; he had seemed to show her sympathy and as suddenly withdrawn it, and during that moment in his wife's bower he had looked at her with cold distaste, with, in fact, an undoubted and inexplicable repulsion.

Katherine went to the slitted window and gazed down to the plain far below, by the river, where she could see the lists and the forked pennants of the contending knights as their identifying flags fluttered from the pavilions. It was high noon now and the hot sun flashed off the silvery armour; great clouds of dust obscured the actual field, but she could hear the roars of excitement from a thousand throats, and the periodic blare of the heralds' trumpets.

She turned into the room and throwing herself across the bed, hit her bruised breast. She winced and though the tiny cuts were healing the pain seemed to strike through to her heart. If I pray to the Blessed Virgin, she thought, perhaps she'll help me, and the forlorn hope brought guilt, for she had missed Mass these two days of hiding in the solar. True, some of the courtiers did not go every day to Mass, Philippa often skipped herself, but the convent habit was strong.

Katherine slipped to her knees on the prie-dieu and began, "Ave Maria gratia plena," but the whispered words echoed bleakly in the empty solar. Then she heard a heavy knock on the oak door.

Katherine, clad only in her linen shift, threw the woollen cloak around her and nervously called, "Come in."

The door opened and Hugh Swynford stood on the threshold looking at her sombrely. He was dressed in full armour, for he was to be an afternoon contender in the lists. His chain-mail hauberk was covered by the ceremonial white silk jupon embroidered with three golden boars' heads on a black chevron, his coat of arms. He looked formidable, and cleaner than she had yet seen him, his crinkled hair as light as straw, his square beard close-trimmed.

He advanced into the room and Katherine stifled a moan and then hot anger rose in her. Holy Blessed Mother, she thought, I pray to you and this is how you reward me!

She wrapped the cloak around her and stood tall and stiff against the wall, her face hardened like the carved stone corbel. "Yes, Sir Hugh," she said. "I'm quite alone and helpless. Have you come to ravish me?"

Hugh's eyes dropped. Dull red crept up from his mailed gorget. "Katherine - I had to see you - I - I bring you this."

He opened his clenched hand, holding it out stiffly, his eyes on the rush-strewn floor. On his calloused palm there lay a massive gold ring, carved claws around a sea-green beryl.

"Take it," he said hoarsely, as she did not move. "The betrothal ring."

"I don't want it," she said. "I don't want it!" She folded her arms tight against her chest. "I don't want to marry you."

His hand closed again over the ring; she saw the muscles of his neck quiver, and the scar on his cheek go white, but he spoke with control.

"It is arranged, damoiselle. Your sister consents, the Duke of Lancaster consents - and the Queen."

"The Queen?" repeated Katherine faintly. "You've seen the Queen?"

"I sent her a message through Lady Agnes. The Queen is pleased."

It was then that Katherine gave up hope. The Queen, the concept of the Queen, had always ruled her destiny as it had her father's. She owed her life to the Queen, and all her loyalty. Of what use was rebellion anyway, for, as Philippa kept asserting, no woman followed her own inclination in marriage. She knew better than to doubt Hugh's word. Brutal and stupid as he might be, he would also be bluntly honest. And now at her continued silence his ready anger flared.

"The Queen thinks me lack-wit to take you, no doubt! They all do. I see them sniggering behind their hands - that scurvy fop de Cheyne -" He scowled towards the window and the noises of the jousting. "His pretty womanish face. Pthaw!" And he spat on the floor.

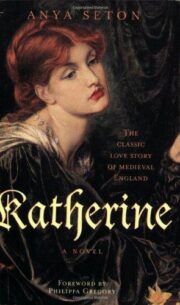

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.