The man with the humped back paused by the market cross some way off, and watched Katherine with compassion.

The voices behind the hedge rose higher. They were shouting London gossip in answer to eager questions from provincial pilgrims. They were recounting with relish the horrors of the revolt in London two months ago, while a Norfolk man insisted that they had had a worse time of it up here than any Londoner could know.

"But 'tis over now for good, that's certain," cried the grocer called Andrew, "since John Ball was caught at Coventry."

"Ay," agreed a self-important voice, "and I was there. With my own two eyes I saw it when the King's men gelded him and gutted him, and he watched his own guts burn - afterwards they quartered him so cannily, he took a rare long time a-dying."

There was laughter until Andrew cried, "Stale news, that is, my friend - but have ye heard the latest of the Duke o' Lancaster?"

Katherine started and opened her eyes. She clenched her hands on the rim of the bench. "John o' Gaunt's renounced his paramour, that's what! Shipped her off to France, or some say to one of his northern dungeons. The King commanded it."

"Nay - but - -" said a woman giggling. " Tis well known he was tired of her anyway and has found someone else, the wicked lecher."

"He'll not dare flaunt his new harlot then, for a Benedictine told me the Duke made public confession of his sins, called his leman witch and whore, then crawled on hands and knees pleading with his poor Duchess to forgive him when they met up in Yorkshire."

Katherine rose from the bench and began to run. The hunchback hurried after her.

She ran north from the town towards the sea and along the banks of the river Stiffkey, until it widened at one place into a mill pond. Here on the grassy bank by a willow tree she stopped. The mill wheel turned sluggishly, as the falling waters pushed on it splashing downward, flowing towards the sea. Katherine advanced to the brink of the pond. She gazed down into the dark brown depths where long grasses bent in the rushing water. She clasped her hands against her breasts and stood swaying on the brink.

She felt a grip on her arm, a deep gentle voice said, "No, my sister. That is not the way."

Katherine turned her head and her wild dilated eyes stared down into the calm tender brown ones of the hunchback. "Jesu, let me be!" she cried on a choking sob. "Leave me alone."

His grip tightened on her arm. "You cry on Jesus' name?" he said softly. "But you do not know what He has promised. He said not that we should not be tempested, nor travailed nor afflicted, but He promised, Thou shalt not be overcome!"

A little wind rustled through the willow fronds, mingling with the sound of the river water as it splashed against the turning mill wheel. She stared at him, while a quiver ran down her back. She did not see him clearly, his brown eyes were part of the beckoning dark depths of the pond. "That was not said for me," she whispered. "God and His Mother have cast me out!"

"Not so. It is not so," he smiled at her. "Since He has said, I shall keep you securely. You're as dearworthy a child of His as anyone."

Katherine's gaze cleared and she recoiled. Now she saw what manner of man it was who was speaking to her. A hideous little man with a hump, whose head was twisted deep into his shoulders. A man with a great purple bulbous nose, scarred by pits, and a fringe of fire-red wisps around a tonsure. She crossed herself, while terror cut her breath. An evil demon - summoned by her from the hell depths of that deep beckoning water. "What are you?" she gasped.

He sighed a little, for he was well used to this, and patiently answered. "I am a simple parson from Norwich, my poor child, and called Father Clement."

Her terror faded. His voice was resonant as a church bell, and his unswerving look met hers with sustaining strength. He wore a much darned but cleanly priest's robe, a crucifix hung from his girdle.

She stepped uncertainly back from the pond, and began to shiver.

"I'll warrant," he said calmly, "you've not eaten in a long time." He opened his pouch, took out slices of buttered barley bread, and a slab of cheese done up in a clean white napkin. "Sit down there," he pointed to a flat stone by a golden clump of wild mustard. "The mustard will flavour the food." He chuckled. "Ah, I make foolish jokes that nobody laughs at but the Lady Julian."

Katherine stared at him dumbly; after a moment, she sat down and took the food.

He saw her wince as she tried to eat and brought her water from the pond in which to soften the bread. He briskly cut the cheese into tiny slivers. While she slowly ate, he pulled a willow whistle from his pouch and with it imitated so perfectly the twitterings of starlings that three of them landed at his feet and twittered answers.

Katherine's physical weakness passed as her stomach filled, but despair rushed back. She folded the white napkin and handed it to Father Clement. "Thank you," she said tonelessly.

"What will you do now?" he asked, putting the napkin and whistle in his pouch. From the bulbous-nosed, pitted face his eyes looked at her with an expression she had seen in no man's eyes before. Love without desire, a kind of gentle merriment.

"I don't know-" she said. "There's nothing for me - nay - -" she whispered, flushing as she saw his question, "I'll not go near - the pond again. But there was no answer for me here at Walsingham, no miracle was wrought." She went on speaking because something in him compelled her to, and it was like speaking to herself. "My fearful sins are yet unshriven - my love - he that was my love now despises me, and my child - -"

Father Clement held his peace. He cocked his massive head against his humped shoulders and waited.

"The cloisters," Katherine said after a while. "There's nothing else. A lifetime of prayer may yet avail to blunt His vengeance. I'll go to Sheppey, to the convent of my childhood. I've given them many gifts through the years. They will take me as a novice."

Father Clement nodded. It was much as he had guessed. "Before you enter this convent," he said, "come with me to the Lady Julian. Speak with her awhile."

"And who is the Lady Julian?"

"A blessed anchoress of Norwich."

"Why should I speak with her?"

"Because, through God's love, I think that she will help you - as she has many - as she once did me."

"God is made of wrath, not love," said Katherine dully. "But since you wish it, I will go. It matters naught what I do."

CHAPTER XXIX

At dusk of the next day when Katherine and the humpbacked parson, Father Clement, rode into Norwich on his mule, Katherine had learned a little about the Lady Julian, though she listened without hope or interest.

Of Julian's early life in the world the priest said nothing, though he knew of the pains and sorrows that had beset it. But he told Katherine of the fearful illness that had come to Julian when she was thirty, and how that when she had been dying in great torment, God had vouchsafed to her a vision in sixteen separate revelations. These "showings" had healed her illness and so filled her with mystic joy and fervour to help others with their message that she had received permission to dedicate her life to this. She had become an anchoress in a cell attached to the small parish church of St. Julian, where folk in need might come to her.

She had been enclosed now for eight years, nor had ever left her cell.

" 'Tis dismal," murmured Katherine, "yet by misery perhaps she best shares the misery of others." "Not dismal at all!" cried Father Clement, with his deep chuckle. "Julian is a most happy saint. God has made a pleasaunce in her soul. No one so ready to laugh as Dame Julian."

Katherine was puzzled, and distrustful. She had never heard of a saint who laughed, nor a recluse who did not dolefully agonise over the sins of the world. It seemed too that though Dame Julian followed the rules prescribed for anchorites, yet these allowed her to receive visitors at times, and that Father Clement had seen her often, when he wrote down her memories of her visions, and the further teachings that came to her through the spirit.

Visions, Katherine thought bitterly. Of what help could it be to listen to some woman's visions? The bleak empty years like a winter sea stretched out their limitless miles before Katherine, and she had no will to live through them. Though the frenzied impulse by the mill pond had passed.

She could not put upon her children the shameful horror of a mother who died by her own act, yet the small Beauforts would never have known. And it were better if everyone thought her dead. The Beauforts then would be less embarrassment to their father. Hawise would care for them, the great castle staffs would care for them, and the Duke, notwithstanding that he had reviled the mother, would provide for them. Tom Swynford was a nearly grown lad and safe-berthed with the young Lord Henry. There was but one child who needed her - and Blanchette was gone.

I will hide me away, thought Katherine, at Sheppey - until I die. Nor would it be long. She felt death near in the increasing pains her body suffered, in the blurring of her sight, and the dragging weakness.

Sometime before they rode through Norwich to the hillside above the river Wensum where Father Clement's little church stood, the priest had fallen into silence. He felt how grievous was the illness of body and soul that afflicted Katherine, and he knew that she was no longer accessible to him.

Guided by Father Clement, Katherine reluctantly entered the dark churchyard behind the flint church. The sky was overcast and an evening drizzle had set in. On the south side beyond the round Saxon church tower, she dimly saw the boxlike outline of the anchorage which clung to the church wall. Breast-high on its churchyard side there was a window, closed by a wooden shutter. The priest tapped on the shutter and called in his bell-toned voice, "Dame Julian, here is someone who has need."

At once the shutter opened. "Welcoom, who'er it be that seeks me."

Father Clement gently pushed Katherine towards the window, which was obscured by a thin black cloth. "Speak to her," he said.

Katherine had no wish to speak. It seemed to her that this was a crowning humiliation, that she should be standing in a tiny unfamiliar churchyard with a hunchback and commanded to reveal her suffering, to ask for help, from some unseen woman whose voice was homely and prosaic as Dame Emma's, and who spoke moreover with a thick East Anglian burr.

"My name is Katherine," she said. Through her weary pain resentment flashed. "There's nothing else to say."

"Coom closer, Kawtherine," The voice behind the curtain was soothing as to a child. "Gi' me your hand." A corner of the black cloth lifted; faintly white in the darkness a hand was held out. Unwillingly Katherine obeyed. At the instant of contact with a firm warm clasp, she was conscience of fragrance. A subtle perfume such as she had never smelled, like herbs, flowers, incense, spices, yet not quite like these. While the hand held hers, she smelled this fragrance and felt a warm tingle in her arm. Then her hand was loosed and the curtain dropped.

"Kawtherine," said the voice, "you are ill. Before you coom to me again, you must rest and drink fresh bullock's blood, tonight, at once - and for days - -"

"By the rood, lady!" Katherine cried angrily, "I've tasted no flesh food in months. 'Tis part of my penance."

"Did our moost Dearworthy Lord Jesus gi' you the penance, Kawtherine?" There was a hint of a smile in the voice, and Katherine's confused resentment increased. Everyone knew that the sinful flesh which had betrayed her must be mortified.

Suddenly the voice changed its tone, became lower, humble and yet imbued with power. Katherine was not conscious of the provincial accent as Julian said, "It was shown to me that Christ ministers to us His gifts of grace, our soul with our body, and our body with our soul, either of them taking help with the other. God has no disdain to serve the body."

For a startled moment Katherine felt a touch of awe. "That is strange to me, lady," she said to the black curtain. "I cannot believe that the foul body is of any worth to God."

"And shall not try tonight," said the voice gently. "Father Clement?"

The priest, who had drawn away, came up to the window. Julian spoke to him at some length.

Katherine was given a chamber reserved for travellers in the rectory across the alley from the church. She was put to bed and cared for by Father Clement's old servant, a bright-eyed woman of sixty, who adored him.

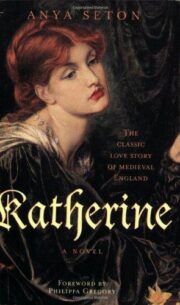

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.