A very great surprise, since he had heard that the Duke had bundled her off abroad, sealed her away in some French convent. He had spent the last ten minutes, not with the woolmongers, but alone, wondering if he should receive her.

Katherine drew a deep breath and laced her hands together. The last time she had seen him, he had been deferential, charming, his eyes moist with covert desire. Now his full handsome face was wary, and he tapped his scarlet shoe impatiently. Ay, it will be like this, she thought. From now on.

"Master Robert, I shall not take much of your time. There are only a few questions I'd like to ask you. I've been a long while on pilgrimage, and know nothing of what has happened in the world."

He flushed again and hawked in his throat.

She saw that he wondered if she even knew of the Duke's renouncement and spoke quickly. "The Duke and I have parted, it was our mutual wish and decision."

He did not believe the latter, but he grunted uneasily. Her low voice softened him, and her dignity. As she spoke, he began to see glimpses of the beauty he had so enviously admired. But she must be thirty now, he told himself sharply, and a discarded mistress - and if it were money that she wanted-

"Master Robert," she said quietly, "have you heard aught of my children?"

"The bastards?" he said startled.

"The Beauforts," she answered.

He swallowed. "Why, I believe they're well - at Kenilworth." His wife, in fact, had been buzzing, since the juicy news about the Duke and Lady Swynford had filtered to Lincoln. Delighted with Lady Swynford's downfall, she had triumphantly garnered every titbit that travellers could tell them.

"How does my manor of Kettlethorpe?" said Katherine. "I know our wool goes through your warehouse."

"The manor does fairly, I think," he said frowning. "At least the clips are up to standard. By God's nails, lady," his jaw dropped, "you don't mean to come back and live at Kettlethorpe!"

"Ah, but I do," said Katherine, smiling faintly. "Where else should I go but my own manor, where my people have need of me? Where else should I bring my children, who have no honest claim on anyone else in the world?"

The wool merchant was dumbfounded. "Surely you mean to sell?" And then take the veil, he thought, far away where no one knows her.

"I will not sell the Swynford holdings," said Katherine, "that were my husband's and belong to my Swynford children - children," she repeated on a lower wavering note.

Sutton looked at her. "I heard the little maid Blanchette was betrothed to some great knight, and already she had a dowry from the Duke. She'll not need Kettlethorpe."

Katherine could not answer. She could not force herself to say, "I don't know where Blanchette is, no one knows but God. But the home she loved and that I took her from will be always waiting."

"Nevertheless," she said, "I shall live at Kettlethorpe. And now, Master Robert, I do humbly beg one thing of you."

He stiffened, crossed his velvet arms over his great barrel chest. "What is it, Lady Swynford?"

"That you will write in my name to the Duke. He has respect for you. He would not accept a letter from me. But I know that he listens to justice. Will you tell him what I propose to do, and will you request in my name that he send me my Beaufort children? Tell him that, when this is done, he shall never be troubled with me again."

Robert Sutton demurred for some time. He pointed out the practicality of her scheme. Her steward was in the Duke's pay, and would undoubtedly be withdrawn. It was folly to think she could run the manor herself, especially since her serfs were known to be unruly - why even here there had been a taint of the iniquitous revolt. Only the most violent suppressive measures had kept the villeins in their places. No doubt she understood nothing of this, having been on pilgrimage so long, but he assured her it was so. Katherine made no reply, except to say that none-the-less she would try to run Kettlethorpe herself.

Then Sutton with increasing embarrassment hinted at the discomfort of her position here; she would be ostracized. The goodwives of Lincoln would be outraged at the reappearance of so notorious a woman, and with her bastards too. Moreover, the bishop was a narrow, strait-laced man with a horror of scandal.

Katherine grew paler as he talked, her grey eyes darkened. But she remarked only that Kettlethorpe was isolated enough, and she would try to trouble no one.

Sutton ended by doing as she wished. He summoned a clerk and dictated the letter to the Duke. When he had finished, a much warmer feeling towards Katherine came over him He could not help but admire her courage, and too, a woman in her position would be grateful for a friend, for a discreet protector. Ay, it was true and unfortunate that Kettlethorpe was isolated, but not so far away that a trip might not be made occasionally. He looked sideways at the slender bare ankles, the faint outline of high firm breasts beneath the hideous black robe, at the cleft chin, the wide voluptuous mouth.

When the clerk had gone, Sutton glanced back into the Hall, saw no one there but servants laying the table. He put his damp hot hand on her bare arm and squeezed. His beard brushed her cheek as he whispered, "You can count on Robert de Sutton, sweet heart, I'll see that you get along."

"Thank you for all your kindness," she said, moving away. "I must go, Master Robert, go home."

Blessed Mary, it would be hard, she thought, as she rode Absalom across the Witham bridge and turned west along the Fossdyke for Kettlethorpe. She needed the Sutton goodwill, for business reasons, as well as for mediation with the Duke. And on the whole she had always liked Master Robert. Yet would it be possible to keep his goodwill, and still deny all the reward which she saw that he would expect?

Hard. The radiance of those revelations had inevitably receded. It shone still, but behind a veil of outer life with its niggling annoyances, worries, hurts. She was no longer simply "Katherine," she must adjust again to the various labels that the world would give her, and the demands fair and unfair that it would make.

She turned north at Drinsey Nook and saw the black forest ahead. The forest where Hugh had hunted, the forest at which she had gazed from the dank solar for so many unhappy years. Soon in the winter the wolves would howl again. She rode through the iron gates that marked the manor road. The mile-long avenue of wych-elms was unchanged; she noted the flocks grazing on her demesne lands, heard a shepherd's shout and the barking of a.dog.

Ahead on the right stood the tithe barn and the little church where lay Nichola, Gibbon - and Hugh. To the left, the shabby manor house where Blanchette had been born, where John had come that morning and saved the baby from Lady Nichola.

The bridge was up, the manor dark. When had it ever welcomed her? She pulled the mule over to the old mounting block, and stepped out of the stirrups. She stood there with her hand on a corner of the gatehouse, looking at the church, at the huddled row of cots that were the village.

You've but to call out to the gate-ward, she thought. But she did not call. She stood there until a small boy came trudging down the lane with an enormous load of faggots on his back. He started and crossed himself when he saw a black figure standing on the mounting block, and Katherine said, "Don't be afraid, lad, I'm Lady Katherine Swynford, this is my home."

The boy gave a sort of snuffling cry, dropped his faggots, and pelted towards the vill, shouting out something Katherine could not hear. That load is too heavy for a child like that, she thought, staring at the faggots. The rain changed to mist. Raw white fog curls floated up from the Trent. Her fingers gripped tight on the rough cold stone beneath her hand. She descended from the block and walked around beneath the gatehouse window. She called, "Gate-ward! Ho, gate-ward!"

There was some movement in the gate loft, a man's voice answered, but it was lost in the pound of running footsteps from the vill. A little man with flying light hair ran towards her and others followed him. "Welcome, dearest lady. Welcome. For sure I told 'em ye'd be coming back some day, would they be patient."

"Cob," she whispered. "Ay, I've come back - -"

"They've been praying for it every day." He jerked his head towards the group behind him. She could not see their separate faces, but she felt their quivering expectancy.

"When I told 'em what ye did for me, what ye'd been through in Lunnon, I told 'em ye went on pilgrimage - oh lady, they've been waiting for ye. 'Tis bad here now - not for me that am a freeman," Cob interjected proudly, "but the unfree - steward's mostly drunk. 'Tis cruel - -"

Katherine lifted her head and looked past Cob to the crowd of her silent, watchful people. "I shall try to make you all glad that I am home," she said.

Part Six (1387-1396)

"And after winter, followeth green May."

(Troilus and Criseyde).

CHAPTER XXX

On Lincoln town's high hill the raw March wind flew incessantly. It chilled bones, reddened noses, afflicted with snuffles and coughs the venerable bishop and the worshipful Mayor John Sutton as well as the ragged beggars who whined for alms in the minster's magnificent Galilee porch.

Wind or no wind - and the citizens were used to it - folk were all out in the streets, frantically nailing banners, greens and coloured streamers to the fronts of houses. It was the twenty-sixth of March, 1387, and King Richard and his Queen Anne were coming to Lincoln that night, the first time that Lincoln had ever been so honoured in the ten years of Richard's reign. The excitement was tremendous. The ostensible reason for this visit was that he and the Queen were to be admitted into the Fraternity of Lincoln Cathedral on the morrow. The actual reason, as many knew, was that Richard had set out on a goodwill tour through all his land. He had felt his popularity slipping, he had been having trouble with commons and lords alike, and with his Uncle Thomas of Woodstock, now Duke of Gloucester - particularly since his Uncle John, the Duke of Lancaster, was at long last in Castile, had been there for a year with Duchess Costanza and their daughter, and his two girls by the Duchess Blanche.

Richard's arrival affected Katherine too. During the six years since her return, she had seldom left Kettlethorpe, nor would have cared to do so now, but the King had commanded it.

On this bleak, windy afternoon, Katherine was sewing by the fire in the pleasant Hall of her town house on Pottergate, just inside the cathedral close. Her lap was filled with a sapphire velvet pool while she put the finishing gold stitches on the mantle she would wear to greet the King. Her sister Philippa sat in an arm-chair, propped with pillows, listlessly pleating a fine gauze veil. Hawise stood behind the kitchen screen pounding almonds into honey for a marchpane while keeping a watchful eye on the housemaids. Little Joan played on the hearth with her kitten. For some time there had been silence, except for Hawise's pounding and the crackle of the fire. The wind howled outside but there was no draught. A good snug house, Katherine thought contentedly.

This was the same house that the Duke had taken for her fifteen years ago when their John Beaufort had been born here, secretly. Three years ago she had decided that the elder boys, John and Harry, would benefit by spending the winter months in Lincoln, where the priests at the newly established Cantilupe Chantry took day scholars. So she had leased this house again. Whereupon the outraged citizenry had shown their displeasure by breaking into her walled close looting and beating the servants.

This was the culmination of many unpleasant incidents, which Katherine had borne with patience. In truth her burdens during these years had been even heavier than she had anticipated. Though her parting from the Duke was known to everyone, she continued to be reviled. Not only moral indignation motivated the folk of Lincoln, but resentment because of city quarrels between the Duke's constable at the castle and the town.

Katherine held herself apart, tried to administer her properties wisely and do the best thing for her little Beauforts. But the vandalism to her Pottergate house was another matter, since it had endangered the boys. She appealed by letter to the King. Richard responded promptly and gallantly, had sent a commission to investigate the charges, and fine the offenders. After that, she had been let alone. Entirely alone. Lincoln folk looked through her when they saw her on the street.

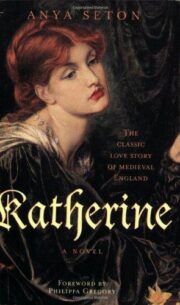

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.