It might be because of that incident three years back, or because Richard had been intrigued by the little mystery when she met him outside Waltham and rescued Cob, or because he thought special notice of her would annoy his enemies - one never knew with Richard. In any case, he had sent word that Katherine was to dine at the bishop's palace on the morrow when the royal party would be there.

The three women in Katherine's Hall were all thinking of the royal visit. "Oh - doux Jesu - Katherine," Philippa sighed, lifting her thin, vein-corded hand and letting it fall despondently. "If only he would present you to the Queen. Then, then, your position might be better here."

Katherine put down her needle and looked at her sister with deep sorrow. Philippa faded daily. Sometimes she suffered much pain from the canker lump in her breast. Her rosy face was shrunken, her eyelids purple, feebleness had blunted her decisive nature. "But the King would not do that, you know, Pica cherie," said Katherine gently. "I don't mind, and I shall as least see her. I'll tell you all about her."

Philippa sighed again. "Anne, Anne, Queen Anne," she said fretfully. "They say she's ugly, with her fat German cheeks, her thick neck. Yet they say he adores her. 'Tis strange - and no heir either - five years - Richard, of course - one always doubted he could - -" Her voice trailed off.

Joan, who had been quiet with her kitten, suddenly looked up at Katherine with big-eyed earnestness. "Mama, why does Sir Thomas hate the King?"

Katherine laughed as mothers do when their children say something precocious, a little embarrassing. "Why, I'm sure he doesn't. What an idea!" She bent down quickly and tied a wisp of blue velvet around the kitten's neck. "There, look at Mimi, isn't she pretty!"

But Joan was not a baby, to be so easily distracted. She was eight, intelligent and practical. A dark pansy-eyed child, round and red-cheeked, she looked much as her Aunt Philippa had, years ago, though she was prettier and had her mother's wide full mouth. "Thomas hates the King," she insisted. "I heard him say so, last year when he was here. He said the King was womanish, soft-bellied and double-tongued as an adder."

"Joan!" cried mother and aunt sharply. The child paid no attention to her aunt, who was usually cross, but she had no wish to provoke her mother's rare displeasure. She hung her head and picked up the kitten.

Katherine, who was always just, stroked the dark curls. "What ever you heard, mouse, forget it. You're old enough to understand that it's dangerous - and discourteous - to say such things about our King. Come, here's a needle for you, let me see what nice stitches you can make."

She gave the delighted child a corner of the velvet mantle and some gold thread. She resumed her own stitching and thought resignedly that the remark sounded like Tom, though she scarcely saw her eldest son, and knew little of what he thought.

Thomas Swynford was almost nineteen now, and a knight. He still served Henry of Bolingbroke, and what emotions he felt seemed to be for his lord. Tom had made two visits to Kettlethorpe since Katherine had come home, had approved, on the whole, her management of his inheritance, loftily ignored his bastard brothers and sisters, and been off again. Katherine knew that he had a dutiful fondness for her, and was also much ashamed of her reputation. He was teller than Hugh had been, but he had the same dusty ram's-wool hair, the same secretiveness. They had one clash. Tom had been angry when he arrived at Kettlethorpe and found that Katherine had been freeing her serfs. She knew better than to argue with him or put forth idealistic reasons, had given him proof instead that a manor worked by free, and devoted, tenants produced more efficiently than one run on the old servile system. Tom had grudgingly scanned the accounts, and ultimately agreed.

Yes, she thought, Tom is a good enough lad. None of her children had given her real anxiety - except - The years had passed without word. All reason demanded acceptance of Blanchette's death in the Savoy - and yet the ache, the void and the question were still there.

The minster bell began to clang for vespers. "The boys will soon be here," said Katherine gladly.

"Ay." Hawise stuck her head around the screen. "And I'd best be hiding me marchpane, them lads'd steal sweeties off the plate o' God himself. Lady," she said severely to Katherine, "put by your sewing, ye mustn't redden your eyes, when ye very well know who's coming to see ye - -"

"Oh Hawise," protested Katherine, with a laugh that mingled affection and exasperation, "you make pothers over nothing."

Hawise snorted rebelliously. Stouter, redder, and nearly toothless, none the less, Hawise was an unchanging rock. Stubborn as a rock too, at times.

"Ye'll not keep him dangling, I should hope!" she cried, wiping her hands on her apron, and stalking up to Katherine.

"By the Virgin, even Katherine couldn't be such a fool!" said Philippa with sudden energy. "Not if she really gets this chance." Philippa and Hawise were at one on this issue. Since the former had come to live with her sister two years ago, these determined women had learned to respect each other.

"Why you both should think he calls here for - for any special reason, I'm sure I don't know," said Katherine, defensively, and as they both opened their mouths for argument, she indicated Joan and shook her head. "Please - -"

Hawise shrugged gathering, up the mantle. "I'll do the last stitches - sweeting, ye're not going to wear that coif! It hides your hair. I'll bring ye the silver fillet."

"Thank God, Hawise has sense," sighed Philippa, lying back on the pillows. "It comforts me to know you'll have her, after I'm gone."

"Don't, dear - that's foolish," said Katherine quickly. "You'll be better when you've taken that betony wine the leech left."

Philippa shook her head and closed her eyes.

Katherine sighed deeply. I shall have to summon Geoffrey soon, she thought. He was living in Kent and dabbling in politics. He and Philippa were happier apart, but the separation was amicable as always, and he would be deeply shocked when he heard of his wife's condition.

Katherine picked up a distaff and began to spin abstractedly while she faced another more immediate worry. What shall I do about Robert Sutton, what is best? She had no real doubt as to the purpose of the wool merchant's announced visit this afternoon. The last time she had seen him he would have declared himself had she not managed to put him off, speaking - as though casually - about his wife, who was then but two months dead. God had helped her through these years. After an embarrassing time with Robert at the beginning, when she had thoroughly dashed all of his amorous hopes, they had settled into a friendly business relationship. Not truly friendly on his part, for Katherine knew he had fallen as deeply in love with her as his cautious, pompous nature would allow.

Katherine twirled the spindle and tried to think coolly. Marriage, honourable marriage with one of Lincoln's foremost citizens. The slandering tongues would be silenced, in public anyway. The lonely struggle would be over, she would be rich, secure. And the children - would it help them? Hawise and Philippa said "Of course." Katherine was not so sure. Robert was a possessive man, her anxious eye had seen indications that he resented the children. Still, she thought, it might be that she imagined his resentment. All her inmost self constantly sought arguments against this practical decision.

Her heart cried out that she did not love him, that the thought of lying in his arms sickened her. Reason answered that at thirty-six she should be finished with youthful passions and love-longings, that stubborn fidelity to a dream long past was stupid.

By day, it was only when she saw his traits in his children that she thought of the Duke. Young John looked most like him, the tawny gold hair, the arrogant grace of movement. But Harry had his voice, deep, sometimes sarcastic, sometimes so caressing, that it turned her heart over. They all had his intense blue eyes, except Joan.

But by night, sometimes she was with him in dreams. In these dreams there was love between them, tenderness greater than there had really been. She awoke from these with her body throbbing and a sense of agonising loss.

She had had no direct communication with him in these years, but he had been just, as she had known he would. There had been legal documents: severance papers sent through the chancery, which allowed her to keep the properties he had previously given her, and made her a further grant of two hundred marks a year for life "in recognition of her good services towards my daughters, Philippa of Lancaster and Elizabeth, Countess of Pembroke." No mention of his Beaufort children, but Katherine understood very well that this generous sum was to be expended for their benefit, and scrupulously did so.

Finally there had been a fearsomely legal quit-claim in Latin which the Duke's receiver in Lincoln translated for her. Its purport was a repudiation of all claims past, present and future which might be made on Katherine by the Duke or his heirs, or that she might make on him. Merely a matter of form and mutual protection, explained the receiver coldly, and added that His Grace with his usual beneficence had ordered that two tuns of the finest Gascon wine be delivered at Kettlethorpe as a final present.

So that was how it ended, those ten years of passionate love. A discarded mistress and her bastards, well enough provided for; a repentant adulterer who had returned to his wife. A common tale, one old as scripture. The Bishop of Lincoln had not failed to point this out in a sermon, with a reference to Adam and Lilith, and a long diatribe about shameless, scheming magdalenes. This sermon was preached at Katherine during the first hullabaloo after her return.

Later the bishop's sensibilities had not been so delicate when Katherine leased the house on Pottergate from the Dean and chapter for a sum double its worth; but she no longer attended Mass in the cathedral, she went instead to the tiny parish church of St. Margaret across the street.

She could not have endured the cruel humiliation that continually assailed her without the memory of Lady Julian, and the golden days in Norfolk. "This is the remedy, that we be aware of our wretchedness and flee to our Lord: for ever the more needy that we be, the more speedful it is to draw nigh to Him." These words always helped, yet on this problem of Robert Sutton she had received no answer. The serene certainty which she had come to rely on after prayer failed her in this.

That afternoon, in anticipation of the wool merchant's visit, Katherine kept her three boys with her. Though they were wild to get out on the exciting streets to watch the preparations for the King's procession, she had asked them to stay awhile, partly because they gave her protection, partly to observe closely how Robert would treat them.

John understood at once. The moment she mentioned her expected visitor, he drew his mother away from the younger boys and putting his hands on her shoulders looked steadily into her face. "Are you going to consent, my mother?" he asked. He was almost fifteen, taller than she was now, broad-shouldered and manly in his school uniform of grey cloth. But she knew how he longed to change it for armour, how he longed for knighthood and deeds of valour, for the life he saw his legitimate half-brothers lead, Henry of Bolingbroke and Tom Swynford.

"Johnny - I don't know," she said sighing. "What shall I do?"

" 'Twould make it easier for you!" he said slowly. Under the new golden fuzz his fair cheeks flushed. "I can't protect you as I would." He gulped and flushed redder, began to twiddle with the flap of his quill case. "But I will! Wait, you'll see! I'll earn my knighthood some way. Mother, I can best all the lads tilting at the quintain. Mother, let me enter the Saint George Day's tournament at Windsor, let me wear plain armour - no one shall guess that I'm - I'm-" Baseborn. He did not say it, it hovered in the air between them.

"We'll see, dear," she said, trying to smile. John's dreams were impractical, but he should at least be attached to some good knight as squire, someone who would honour his royal blood and not take advantage of his friendless position.

And the two other boys. She looked at Harry, sprawled on his stomach by the fire, reading as usual. He had ink on his duckling-yellow forelock, ink stains and penknife cuts on his grimy hands. A true scholar was Harry, with a keen shrewd mind beyond his years. He gulped knowledge insatiably, and yet retained it. He was determined to go to Cambridge, to Peterhouse, and train for minor orders at least; any further advancement in the clergy would take great influence - and money. A bastard could not advance in the Church without them. Bastardy. How often had she tried to console the elder boys as they had grown into realisation of the barrier that held them back from their ambitions, pointing out that they were not nameless, that their father had endowed them with a special badge, the Beaufort portcullis, and a coat of arms, three royal leopards on a bar. She reminded them that William of Normandy, England's conqueror, was not true-born. These arguments seemed to comfort the boys. At least they had both ceased to distress her with laments. But they were thoughtful of her always. In their different ways, they loved her dearly.

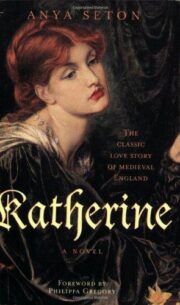

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.