I am the ground of thy beseeching. How shouldest thou not then have thy beseeching? Ay, she believed that. Many times comfort had been given her, and a glimpse of grace. Yet there were arid spaces like now when the light dwindled into greyness and she fell into the sloth and doubt which Lady Julian considered the only true sins.

The door to the outside staircase flew open with a bang. Hawise came in on a stinging blast of cold air. "Cock's bones, but 'tis fine weather for friars!" She slammed the door shut and blew on her fingers. "No matter, sweeting, 'tis your saint's day, and I've laced your ale wi' cinnamon special as ye like it. Bless ye!" She leaned over the bed and gave Katherine a kiss. "Peter, what a long face! What's a matter?"

"I don't know - I've got the dumps." Katherine tried to smile. "Hawise, do you know how old I am?"

"I ought to." Hawise poured steaming ale into a cup and poked at the fire embers. "I've not lost me memory yet, let alone that all the kitchen folk're busy painting red ribbons 'round forty-five candles for your feast tonight."

"Forty-five," said Katherine flatly. "Jesu, what an age!"

Hawise came bade to the bed holding out a rabbit-lined chamber robe. "Well, ye've not gone off much, if that's any comfort. Cob was boasting only yestere'en that the Lady o' Kettlethorpe is the fairest woman in Lincolnshire."

"Cob is partial, bless him," said Katherine with a rueful laugh. She looked down at her long braids, thick as ever but lightly frosted with silver, while at her temples she knew well that there were two white patches springing up with startling effect against the dark bronze.

"Ye're still firm as an apple," said Hawise casting a critical look as she enfolded Katherine in the chamber robe. " 'Tis all the work ye do, Saint Mary, I'd never've believed it in the old days - brewing, baking, distilling, churning along wi' the maids - running here, running there, tending to the cotters - gardening, even shearing. Lord what busyness!"

"Well, I've had to," said Katherine bleakly. There had been a bad couple of years after Sutton withdrew his advice and support. She had run the manor entirely alone, but they struggled through to modest profit again. Sutton's outraged feelings had eventually been soothed by marriage with the daughter of a wealthy knight. And it all seemed very long ago.

She went mechanically through the process of washing and dressing, allowed Hawise to bedeck her in the gala robe of deep crimson velvet edged with squirrel and fasten the bodice with the Queen's brooch.

"Seems strange too," said Hawise, adjusting the clasp, "what coffers full o' jewels I used to rummage in afore we'd find one to your liking - and now there's naught to wear but this thing."

Katherine sighed and sat down by the fire. "So much has changed," she said sadly. "Hawise - I think of my poor sister this morning, God rest her soul. So many deaths - -"

"Christ-a-mercy - lady-" cried Hawise crossing herself.

"What a way to talk on your saint's day!"

"What better day?" said Katherine. "Since I am thinking of them - -" She fell silent, staring into the fire.

Ay, o' one death especial, thought Hawise as she shook her head and started to straighten the bedsheets. The Duchess. Last year had come a strange smiting on the highest ladies of the land, the Lollard preachers had seen God's vengeance in it, and folk had been afraid. Between Lent and Lammastide, they died, the three noblest ladies in England. Queen Anne, she died of plague at Sheen Castle, and the King had gone out of his mind with grief. Mary de Bohun, Lord Henry of Bolingbroke's countess, had died in childbirth, Christ have mercy on her, thought Hawise, remembering the frightened twelve-year-old bride at Leicester Castle the winter before the revolt.

And the Duchess Costanza had died, here in England, of some sickness in her belly, they said. When the news got to Kettlethorpe, Lady Katherine had been very quiet for many days, her beautiful grey eyes had taken on a strained, waiting look, but nothing had happened at all, except that the Beaufort children had all been sent fresh grants through the chancery. In truth, through the last years, the Duke seemed to have taken a concealed interest in them; at least he had not interfered with the marked favour and help that his heir Henry had occasionally shown them.

But, thought Hawise, tugging viciously at a blanket, wouldn't you think the scurvy ribaud might have sent my Lady some kindly word, at last? Instead he had gone off to Aquitaine again as ruler. And was still there, God blast him, and why hadn't she taken that Sutton when she had the chance, though to be sure he might not have made her happy. Men, men, men, thought Hawise angrily, then seeing that Katherine still sat in dismal abstraction, she went up to her coaxingly. "Read some o' those merry tales in the book Master Geoffrey sent ye, now do. They always cheer ye."

Katherine blinked and sighed. "Oh Hawise - I fear 'twould take more than the tales of junketing to Canterbury to cheer me today - poor Geoffrey - -" He was having a hard time, she knew, though his letters were philosophical as always, yet he was in financial difficulties, his health not good, and he was lonely in the Somerset backwater where he had been consigned as Royal Forester. I wish I could help him, she thought. Perhaps when the accounts are all toted up, there may be a shilling or so to spare here - -

"Hark!" said Hawise suddenly, pulling a wry mouth. "There's my Lady Janet with the twins." They both listened to the familiar clatter of hooves in the courtyard, and heard the peevish howling of babies.

"Yes," said Katherine rising and reaching for her mantle. "The day's festivities most merrily commence."

That's not like her, Hawise thought gloomily, while she continued to straighten the solar, that dry bitter inflexion from one who had shown of late years a nearly constant sweetness and courage. Hawise paused by the prie-dieu and picking up her mistress' beads said a rosary for her. Still dissatisfied, she hunted through Katherine's dressing coffer until she found a little brass pin which she threw into the fire with a wish, and felt better. "Cry before breakfast, sing before supper," she quoted from Dame Emma's collection of comforting lore.

Hawise's prayer and wish were granted, though not before supper and by nothing as simple as cheerful song.

The villagers had finished their feasting, the boards had been cleared, and stacked with the trestles in the corner of the Hall. Cob had made his speech. He had sent hot colour to Katherine's cheeks, mist to her eyes with his eulogies, and her tenants had cheered her exuberantly. Two ne'er-do-wells from Laughterton had even brought her some back rent that she had despaired of getting, and there had been copious donations of apples, and little cakes baked by the village wives.

Now Katherine sat on in the hour before bed strumming her lute, while Joan sang and Janet listened vaguely. The twins were asleep in their cradle by the hearth. Hawise sat by the kitchen screen mending sheets. The house carls had all gone off to the village tavern to wind up the day. The forty-five big candles still burned, and shed unusual brilliance in the old Hall.

"I wonder where my brothers all are tonight?" said Joan in a pause between songs. "Lord, I wish I was a man."

Her mother's heart tightened. So dreary for the child here in this middle-aged woman's household, such tame distractions to offset the cankering hidden love.

"Well," said Katherine lightly, "we know Harry's studying in Germany and Tamkin is supposed to be at Oxford, though I wouldn't count on it." She smiled. Tamkin was no scholar like Harry, who had already risen further in the Church than had ever seemed possible. There could be no doubt that their father's secret influence had helped them all. This had often comforted her. Young John had achieved at last his great ambition and been knighted, after he travelled with Lord Henry to the Barbary Coast. A lovable fellow Johnnie was and had made his way as a soldier of fortune, despite the hindrance of his birth. Even Richard liked him - so far anyway - and had taken him with the army to Ireland last year.

"I don't know where Thomas is," said Janet suddenly in her plaintive whine. "I hope he gets home for Christmas; he never lets me know anything."

"Poor Janet." Katherine put down the lute and sighed. "Waiting is woman's lot. I don't suppose I'll see my Johnnie for many a long day, either."

Janet's small pale eyes sent her mother-in-law a resentful look. A blind mole could see that Lady Katherine preferred her baseborn sons to her legitimate one, and Janet considered this shameful. Her discontented gaze roamed around the Hall, which was larger and better furnished than Coleby's. She indulged in a familiar calculation as to how long it would be before Tom inherited. But Lady Katherine seemed healthy enough and looked, most infuriatingly, ten years younger than she was, a manifestly unfair reward for a wicked life.

"I think I'll go to bed," said Joan yawning. "With you, I suppose, Mother?"

Katherine nodded. The arrival of guests always meant switch of sleeping quarters. Janet, nurse and twins would occupy Joan's usual tower chamber - that had once been Nichola's.

Hawise put down her mending and began to blow out the candles. There were still twenty to go when the dogs started to bark outside. The blooded hound, Erro, that Sutton had given young John over eight years ago had been lying by the fire with his head on his paws. A dignified aristocrat, Erro, who did not consider himself a watchdog, and usually ignored the noisy antics of his inferiors. It was therefore astonishing to have him raise his head and whine, then leap up with one powerful bound and precipitate himself uproariously against the door.

"Strange," said Katherine running to hold his collar. "There's only one - Sainte Marie, could it be?" she added joyously.

And it was. Young John Beaufort came into the Hall on a swirl of soft snow. He caught his mother in his arms, kissed her heartily. "God's greeting, my lady! Sure your saint might have sent better weather to a son who's been hurrying to you these many days!"

He kissed his sister, Hawise, and, less enthusiastically, Janet, before quieting the ecstatic Erro, who barked fit to raise the dead in the churchyard across the road. John stood by the fire while the women fluttered around him removing his mantle, brushing snow from his curling yellow hair, unfastening his sword, and the gold knight's spurs of which he was so proud, heating ale for him in the long-handled iron pot over the fire.

"Oh dearling," Katherine cried, quivering with pride - surely there was no comelier young man in England - ''and you remembered your old mother's feast day! Johnnie, this is the pleasantest surprise, the goodliest thing that's happened to me in an age. I thought you abroad!"

"Well, I was." He sank into a chair with a grunt, held his steaming red-leather shoes towards the fire. "Until three weeks ago. In Bordeaux. Mother-" He turned and looked directly into her face. "I was not the only one there who remembered your saint's day."

Katherine's look of contented pride slowly dissolved, to be replaced by tenseness. She said slowly, "What were you doing at Bordeaux, Johnnie?"

Hawise's hands, which had been rubbing lard into John's wet shoe-leather, suddenly stilled. Janet ceased jiggling the twin's cradle and raised her head, not understanding the odd tone in her mother-in-law's voice. Joan looked from her mother to her brother and began to breathe fast.

"I was summoned by my father!"cried John triumphantly. "I spent a week with him and have brought you a letter from him. He wanted it to reach you today."

In Katherine's head there was a rumble like far-off thunder, while she felt a peculiar coolness as though the snow outside were melting through her veins.

"So you have met the Duke again," she said speaking from the depths of the coolness. "How does he seem?"

John's surprise that she did not at once ask for her letter was shared by Joan and Janet, but Hawise understood. She returned grimly to the shoe-leather and thought, Now what does that accursed Duke want?

"He's very tired, I think," said John, "and lean as - as Erro here, anxious to be back. His work is finished in Aquitaine, and Richard has summoned him home, much to Gloucester's fury, I believe."

"Ah - -" said Katherine.

"By God," said John eagerly, "of course, that stinking Thomas of Woodstock wants our father's grace kept out of the country, so he can have free hand with Richard and the foul plottings and warmongerings that Father holds in check. Richard's fed up for the time and is pro-Lancaster now."

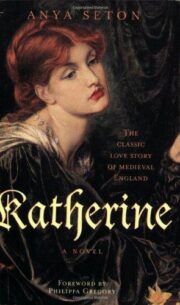

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.