“And they are pleased with you … up at the chateau. That is obvious.

Monsieur Ie Comte looked this afternoon as though he approved of. of you. “

“Yes, I think he is pleased. I flatter myself that I have done good work on his pictures.”

He nodded.

“You must not leave us, Dallas,” he said.

“You must stay with us. We could not be happy if you went away … none of us.

Myself especially. “

“You are so kind….”

“I will always be kind to you … for the rest of our lives. I could never be happy again if you went away. I am asking you to stay here always … with me.”

“Jean Pierre!”

“I want you to marry me. I want you to assure me that you will never leave me … never leave us. This is where you belong. Don’t you know it, Dallas?”

I had stopped short and he slipped his arm through mine and drew me into the shelter of one of the trees.

“This could not be,” I said.

“Why not? Tell me why not?”

“I am fond of you … I shall never forget your kindness to me when I first came here …”

“But, you are telling me, you do not love me?”

“I’m telling you that although I am fond of you I don’t think I should make you a good wife.”

“But you do like me, Dallas?”

“Of course.”

“I knew it. And I will not ask you to say yes or no now. Because it may be that you are not ready.”

“Jean Pierre, you must understand that I…”

“I understand, my dearest.”

“I don’t think you do.”

“I shall not press the matter but you will not leave us. And you will stay as my wife… because you could not bear to leave us … and in time … in time, my Dallas … you will see.”

He took my hand and kissed it quickly.

“Do not protest,” he said.

“You belong with us. And there can be no one else for you but me.”

Genevieve’s voice broke in on my disturbed thoughts.

“Oh, there you are, miss. I was looking for you. Oh, Jean Pierre, you must dance with me. You promised you would.”

He smiled at me; I saw the lift. of the eyebrows as expressive as that of the shoulders.

As I watched him dance away with Genevieve, I was vaguely apprehensive. For the first time in my life I had received a proposal of marriage. I was bewildered. I could never marry Jean Pierre. How could I when. Was it because I had betrayed my feelings? Could it be that as he stood at my stall that afternoon the Comte had betrayed his?

The joy had gone out of the day. I was glad when the dancing was over, when the “Marseillaise’ had been played and the revellers went home and I to my room in the chateau to think of the past and grope blindly towards the future.

I found it difficult to work the next day and I was afraid that I should damage the wall-painting if I continued in this absentminded mood. So I accomplished little that morning, but my thoughts were busy. It seemed incredible that I who since my abortive affair with Charles had never had a lover should now be attractive to two men, one of whom had actually asked me to marry him. But it was the Comte’s intentions that occupied my thoughts. He had looked younger, almost gay, when he had stood by the stall yesterday. I was certain in that moment that he could be happy; and I believed that I was the one to make him so. What presumption! The most he could be thinking of was one of those light love affairs in which it seemed he indulged from time to time. No, I was sure it was not true.

After I had taken breakfast in my room Genevieve burst in on me. She looked at least four years older because she had pinned her long hair into a coil on the top of her head which made her taller and more graceful.

“Genevieve, what have you done?” I cried.

She burst into loud laughter.

“Do you like it?”

“You look … older.”

“That’s what I want. I’m tired of being treated like a child.”

“Who does treat you so?”

“Everybody. You, Nounou, Papa … Uncle Philippe and his hateful Claude … Just everybody. You haven’t said whether you like it.”

“I don’t think it… suitable.”

That made her laugh.

“Well, I think it is, miss, and that is how I shall wear it in future. I’m not a child any more. My grandmother married when she was only a year older.”

I looked at her in astonishment. Her eyes were gleaming with excitement. She looked wild; and I felt very uneasy, but I could see it would be useless to talk to her.

I went along to see Nounou, and asked after her headaches. She said they had troubled her less during the last few days.

“I’m a little anxious about Genevieve,” I told her. The startled look came into her eyes.

“She’s put her hair up. And she no longer looks like the child she is.”

“She is growing up. Her mother was so different… always so gentle.

She seemed a child after Genevieve’s birth. “

“She said that her grandmother was married when she was sixteen … almost as though she were planning to do the same.”

“It’s her way,” said Nounou.

But two days later Nounou came to me in some distress and told me that Genevieve who had gone out riding alone that afternoon had not come home. It was then about five o’clock.

I said: “But surely one of the grooms was with her. She never goes riding alone.”

“She did today.”

“You saw her?”

“Yes, from my window. I could see she was in one of her moods so I watched. She was galloping across the meadow and there was no one with her.”

“But she knows she’s not allowed …”

I looked at Nounou helplessly.

“She has been in this mood since the kermes se sighed Nounou.

“And I was so happy to see how interested she was. Then … she seemed to change.”

“Oh, I expect she’ll be back soon. I believe she just wants to prove to us that she’s grown up.”

I left her then and in our separate rooms we waited for Genevieve’s return. I guessed that Nounou, like myself, was wondering what steps we should have to take if the girl had not returned within the next hour.

We were spared that, for half an hour or so after I had left Nounou, from my window I saw Genevieve coming into the castle.

I went to the schoolroom through which she would have to pass to her own bedroom, and as I entered Nounou came out of her room.

“She’s back,” I said.

Nounou nodded.

“I saw her.”

Shortly afterwards Genevieve came up.

She looked flushed and almost beautiful with her dark eyes brilliant.

When she saw us waiting there she smiled mischievously at us and taking off her hard riding-hat threw it on the schoolroom table.

Nounou was trembling and I said: “We were anxious. You know you are not supposed to go riding alone.”

“Really, miss, that was long ago. I’m past that now.”

“I didn’t know it.”

“You don’t know everything although you think you do.”

I was deeply depressed, because the girl who stood before us defying us, jeering at us, was no different from the one who had been so rude to me on my arrival. I had thought that we had made some progress but I realized there had been no miracle. Although she could be interested and pleasant, she was wild as ever when the desire to be so took possession of her.

“I am sure your father would be most displeased.”

She turned to me angrily.

“Then tell him. Tell him. You and he are such friends.”

I said angrily: “You are being absurd. It is very unwise for you to ride alone.”

She stood still smiling secretly and I wondered in that moment whether she had been alone. The thought was even more alarming.

Suddenly she swung round and faced us.

“Listen,” she said, ‘both of you. I shall do as I like. Nobody . just nobody . is going to stop me. “

Then she picked up her hat from the table and went into her room slamming the door behind her.

Those were uneasy days. I had no wish to go to the Bastides’, for I feared to meet Jean Pierre and I felt that the pleasant friendly relationship which I had always enjoyed would be spoilt. The Comte had gone up to Paris for a few days after the kermes se Genevieve avoided me. I tried to throw myself even more wholeheartedly into work and now that more of the wall-painting was emerging this helped my troubled mind.

I was working one morning when I looked up suddenly and found that I was not alone. This was an unpleasant habit of Claude’s. She would come into a room noiselessly and one would be startled to find her there.

She looked very pretty that morning in a blue morning gown, piped with burgundy-coloured ribbon. I smelt the faint musk-rose scent she used.

“I hope I didn’t startle you, Mademoiselle Lawson?” she said pleasantly.

“Of course not.”

“I thought I would speak to you. I am growing more and more uneasy about Genevieve. She is becoming impossible. She was very rude to me and to my husband this morning. Her manners seem to have deteriorated lately.”

“She is a child of moods but she can be charming.”

“I find her extremely ill-mannered and gauche. I hardly think any school would want her if she behaved like this. I noticed her behaviour with the wine-grower at the kermes se In her present mood there could be trouble if she became too headstrong. She can no longer be called a child and I fear she might form associations which could be dangerous.”

I nodded, for I understood clearly what she meant. She was referring to Genevieve’s obsession with Jean Pierre.

She moved closer to me.

“If you could use your influence with her … If she knew we were concerned she would be all the more reckless. But I can see you realize the dangers.”

She was looking at me quizzically. I guessed she was thinking that if there should be trouble of the nature she was hinting at, I should in a way be to blame. Wasn’t I the one who had fostered this friendship?

Genevieve had scarcely been aware of Jean Pierre before my friendship with the family.

I felt uneasy and a little guilty.

She went on: “Have you thought any more of that proposition I put to you the other day?”

“I feel I must finish my work here before I consider anything else.”

“Don’t leave it too long. I heard a little more about it yesterday.

One of the party is thinking of starting an exclusive art school in Paris. I think there would be a very good opening there. “

“It sounds almost too good to be true.”

“It’s a chance in a lifetime, I should imagine. But, of course, the decision will have to be made fairly soon.”

She smiled at me almost apologetically and left.

I tried to work but I could not put my mind to it. She wanted me to go. That much was evident. Was she piqued because some of that attention which she felt should be hers was given to me by the Comte?

It might be. But was she also genuinely concerned for Genevieve? This would be, I was ready to admit, a very real problem. Had I misjudged her?

I soon became convinced that Claude was really concerned about Genevieve. That was when I heard her in deep conversation with Jean Pierre in the copse in which the Comte had had his accident. I had been to see Gabrielle and was on my way back to the chateau and had taken the short cut through the copse, when I heard their voices.

I did not know what was said and I wondered why they had chosen such a rendezvous. Then it occurred to me that the meeting might not have been arranged. They had met by chance and Claude had decided to take the opportunity of telling Jean Pierre that she did not approve of Genevieve’s friendship with him.

It was, after all, no concern of mine and I turned hastily away.

Skirting the copse, I rode back to the chateau. But the incident confirmed me in my opinion that Claude really was worried about Genevieve. And in my pride I had thought her main feeling was jealousy of the Comte’s interest in me!

I tried to put all these disturbing matters out of my mind by concentrating on my work. The picture was growing-and there she was before me the lady with the emeralds, for discoloured as they were I could see by the shape of the ornaments that they were identical to those which I had seen on the first picture I had cleaned. The same face. This was the woman who had been the mistress of Louis XV and had started the emerald collection. In fact the picture was very like the other except that in this her dress was of blue velvet and in the other red and in this one, of course, nestling against the blue velvet of her skirt was the spaniel. It was the inscription that puzzled me.

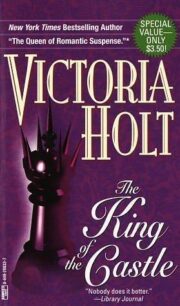

"King of the Castle" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "King of the Castle". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "King of the Castle" друзьям в соцсетях.