Surely I was beyond that sort of behaviour.

He had not been to see how the wall-painting was progressing, which surprised me. At times I wondered whether Claude talked of me to him and they smiled together at my innocence. If it were true that she was to have his child then they would be very intimate, I couldn’t believe it but that was the romantic woman in me. Looking at the situation from a practical point of view it seemed logical enough and weren’t the French noted for their logic? What to my my English reasoning would seem an immoral situation, to their French logic would seem satisfactory. The Comte, having no desire for marriage yet wishing to see his son inherit the name, fortune, estates and everything that was important to him; Philippe as his reward would inherit before the boy if the Comte should die, and the chateau was his home; Claude could enjoy her relationship with her lover without suffering any loss of dignity. Of course it was reasonable; of course it was logical.

But to me it was horrible and I hated it, and I did not try to see him for I feared I should betray my feelings. In the meantime I was watchful.

One afternoon I walked over to see Gabrielle, now very obviously pregnant and contented. I enjoyed my visit, for we talked of the Comte and Gabrielle was one of the people who had a high regard for him.

When I left her I took the short cut through the woods and it was while I was there that the feeling of being followed came upon me more strongly than before. On this occasion I was truly alarmed. Here was I alone in the woods those very woods in which the Comte had received his injury. The fear had come suddenly upon me, with the crackle of undergrowth, the snapping of a twig.

I stopped and listened. All was silent; and yet I was conscious of danger.

An impulse came to me to run and I did so. Such panic possessed me that I almost screamed aloud when my skirt was caught by a bramble. I snatched it away leaving a little of the stuff behind, but I did not stop.

I was certain I heard the sound of hurrying steps behind me, and when the trees thinned out I looked behind me, but there was no one.

I came out of the copse. There was no sign of anyone emerging from the woods, but I did not pause long. I started the long walk back to the chateau.

Near the vineyards I met Philippe on horseback.

He rode up to me and as soon as he saw me exclaimed:

“Why Mademoiselle Lawson, is anything wrong?”

I guessed I still looked a little distraught so there was no point in hiding it.

“I had rather an unpleasant experience in the woods. I thought I was being followed.”

“You shouldn’t go into the woods alone, you know.”

“No, I suppose not. But I didn’t think of it.”

“Fancy, I dare say, but I can understand it. Perhaps you were remembering how you found my cousin there when he was shot, and that made you imagine someone was following you. It might have been someone after a hare.”

“Probably.”

He dismounted and stood still to look at the vineyards.

“We’re going to have a record harvest,” he said.

“Have you ever seen the gathering of the grapes?”

“No.”

“You’ll enjoy it. It won’t be long now. They’re almost ready. Would you care to take a look into the sheds? You’ll see them preparing the baskets. The excitement is growing.”

“Should we disturb them?”

“Indeed not. They like to think that everyone is as excited as they are.”

He led me along a path towards the sheds and talked to me about the grapes. He admitted that he had not attended a harvest for years. I felt embarrassed in his company. I saw him now as the weak third party in a distasteful compact. But I could not gracefully make my escape.

“In the past,” he was saying, “I used to stay at the chateau for long periods in the summer, and I always remembered the grape harvest. It seemed to go on far into the night and I would get out of bed and listen to them singing as they trod the grapes. It was a most fascinating sight.”

“It must have been.”

“Oh, yes, Mademoiselle Lawson. I never forgot the sight of men and women stepping into the trough and dancing on the grapes. And there were musicians who played the songs they knew and they danced and sang. I remembered watching them sink lower and lower into the purple juice.”

“So you are looking forward to this harvest.”

“Yes, but perhaps everything seems more colourful when we are young.

But I think it was the grape harvest which decided me that I’d rather live at Chateau Gaillard than anywhere else on earth. “

“Well, now you have that wish.”

He was silent and I noticed the grim Jines about his mouth. I wondered what he felt about the relationship between the Comte and his wife.

There was an air of effeminacy about him which made more plausible Claude’s account, and the fact that his features did in some way resemble those of his cousin made this complete difference in their characters the more apparent. I could believe that he wanted more than anything to live at the chateau, to own the chateau, to be known as the Comte de la Talle, and for all this he had bartered his honour, and married the Comte’s mistress and would accept the Comte’s illegitimate son as his . all for the sake of one day, if the Comte should die, being King of the Castle, for I was sure that if he had refused to accept the terms laid down by the Comte, he would not have been allowed to inherit.

We talked of the grapes and the harvests he remembered from his childhood and when we came to the sheds I was shown the baskets which were being prepared and I listened while Philippe talked to the workers.

He walked his horse back to the chateau and I thought him friendly, reserved, a little deprecating, and found myself making excuses for him.

I went up to my room and as soon as I entered it I was aware that someone had been there during my absence.

I looked about me; then I saw what it was. The book I had left on my bedside table was on the dressing-table. I knew I had not left it there.

I hurried to it and picked it up. I opened the drawer. Everything appeared to be in order. I opened another and another. Everything was tidy.

But I was sure that the book had been moved.

Perhaps, I thought, one of the servants had been in. Why? No one usually came in during that time of day.

And then on the air I caught the faint smell of scent. A musk-rose scent which I had smelt before. It was feminine and pleasant. I had smelt it when Claude was near.

I was certain then that while I was out Claude had been in my room.

Why? Could it be that she knew I had the key and had she come to see if I had hidden it somewhere in my room?

I stood still and my hands touched the pocket of my petticoat through my skirt. There was the key safe on my person. The scent had gone.

Then again there it was faint, elusive, but significant.

It was the next day when the maid brought a letter to my room from Jean Pierre, who said he must see me without delay. He wanted to speak to me alone so would I come to the vineyards as soon as possible where we could talk without being interrupted. He begged me to come.

I went out into the hot sunshine, across the drawbridge and towards the vineyards. The whole countryside seemed to be sleeping in the hot afternoon; and as I walked along the path through the vines now laden with their rich ripe fruit Jean Pierre came to meet me.

“It’s difficult to talk here,” he said.

“Let’s go inside.” He took me into the building and to the first of the cellars.

It was cool there and seemed dark after the glare of the sun; here the light came through small apertures and I remembered hearing how it was necessary to regulate the temperature by the shutters.

And there among the casks Jean Pierre said: “I am to go away.”

“Go away,” I repeated stupidly. And then: “But when?”

“Immediately after the harvest.”

He took me by the shoulders.

“You know why, Dallas.”

I shook my head.

“Because Monsieur Ie Comte wants me out of the way.”

“Why?”

He laughed bitterly.

“He does not give his reasons. He merely gives his orders. It no longer pleases him that I should be here so, although I have been here all my life, I am now to move on.”

“But surely if you explain …”

“Explain what? That this is my home … as the chateau is his? We, my dear Dallas, are not supposed to have such absurd sentiments. We are serfs … born to obey. Did you not know that?”

“This is absurd, Jean Pierre.”

“But no. I have my orders.”

“Go to him … tell him … I am sure he will listen.”

He smiled at me.

“Do you know why he wants me to go away? Can you guess? It is because he knows of my friendship with you. He does not like that.”

“What should it mean to him?” I hoped Jean Pierre did not notice the excited note in my voice.

“It means that he is interested in you … in his way.”

“But this is ridiculous.”

“You know it is not. There have always been women … and you are different from any he has ever known. He wants your undivided attention … for a time.”

“How can you know?”

“How can I know? Because I know him. I have lived here all my life and although he is frequently away, this is his home too. Here he lives as he can’t live in Paris. Here he is lord of us all. Here we have stood still in time and he wants to keep it like that.”

“You hate him, Jean Pierre.”

“Once the people of France rose against such as he is.”

“You’ve forgotten how he helped Gabrielle and Jacques.”

He laughed bitterly.

“Gabrielle like all women has a fondness for him.”

“What are you suggesting?”

“That I don’t believe in this goodness of his. There’s always a motive behind it. To him we are not people with lives of our own. We are his slaves, I tell you. If he wants a woman then anyone who stands in his way is removed and when she is no longer required, well… You know what happened to the Comtesse.”

“Don’t dare say such things.”

“Dallas! What’s happened to you?”

“I want to know what you were doing in the gun-room at the chateau.”

“I?”

“Yes, I found your grape scissors there. Your mother said you had missed them and that they were yours.”

He was taken aback a little. Then he said: “I had to go to the chateau to see the Comte on business . that was just before he went away. “

“And he took you to the gun-room?”

“No.”

“But that’s where I found them.”

“The Comte wasn’t at home so I thought I’d have a look round the chateau. You’re surprised. It’s a very interesting place. I couldn’t resist looking round. That was the room, you know, where an ancestor of mine last saw the light of day.”

“Jean Pierre,” I said, ‘you shouldn’t hate anyone so much. “

“Why should it all be his? Do you know that he and I are blood relations? A great-great-grandfather of mine was half-brother to a Comte the only difference was that his mother was not a Comtesse.”

“Please don’t talk like this.” A terrible thought struck me and I said: “I believe you would kill him.”

Jean Pierre did not answer and I went on: “That day in the woods…”

“I didn’t fire that shot. Do you imagine I’m the only one who hates him?”

“You have no reason to hate him. He has never harmed you. You hate him because he is what he is and you want what he has.”

“It’s a good reason for hating.” He laughed suddenly.

“It’s just that I’m furious with him now because he wants to send me away. Wouldn’t you hate anyone who wanted to send you away from your home and the one you loved? I did not come here to talk of hating the Comte but of loving you. I shall go to Mermoz when the harvest is over and I want you to come with me, Dallas. You belong here among us. After all we are your mother’s people. Let us be married and we will laugh at him then. He has no power over you.”

No power over me! I thought: but you are wrong, Jean Pierre. No one has ever before had this power to regulate my happiness, to excite and depress me.

Jean Pierre had seized my hands; he drew me towards him, his eyes shining.

“Dallas, marry me. Think how happy that you will make us all-you, me, my family. You are fond of us, aren’t you?”

“Yes,” I said, “I am fond of you all.”

“And do you want to go away… back to England? What will you do there, Dallas, my darling? Have you friends there? Then why have you been content to leave them so long? You want to be here, don’t you?

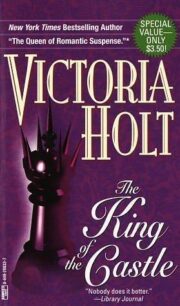

"King of the Castle" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "King of the Castle". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "King of the Castle" друзьям в соцсетях.