“Trit-Trot?” While he took the place beside her, Eve took off her bonnet and set it aside, then smoothed her hand over her hair.

When that little delaying tactic was at an end, she grimaced. “Louisa finds these appellations and applies them indiscriminately to the poor gentlemen who come to call. She’s gotten worse since she married. Tridelphius Trottenham, ergo Trit-Trot, and it suits him.”

“Dear Trit-Trot has a gambling problem.”

One did not share such a thing with the ladies, generally, but if the idiot was thinking to offer for a Windham daughter, somebody needed to sound a warning.

And as to that, the idea of Trit-Trot—the man was now doomed to wear the unfortunate moniker forevermore in Deene’s mind—kissing any of Moreland’s young ladies, much less kissing Eve, made Deene’s sanguine mood… sink a trifle.

“He also clicks his heels in the most aggravating manner,” Eve said, her gaze fixed on a bed of cheery yellow tulips. “And he doesn’t hold a conversation, he chirps. He licks his fingers when he’s eaten tea cakes, though he’s a passable dancer and has a kind heart.”

Bright yellow tulips meant something in the language of flowers: I am hopelessly in love. In his idiot youth, Deene had sent a few such bouquets to some opera dancers and merry widows.

Rather than ponder those follies, Deene considered the woman beside him. “I never gave a great deal of thought to how much you ladies must simply endure the company of your callers. Is it so very bad?”

She shifted her focus up, to where a stately oak was sporting a reddish cast to its branches in anticipation of leafing out. “It’s worse now that Sophie, Maggie, and Louisa are married. One heard of the infantry squares at Waterloo, closing ranks again and again as the French cavalry charged them. I expect we two youngest sisters share a little of that same sense.”

Oak leaves for bravery.

He spoke slowly, the words dragged past his pride by the mental plough horse of practicality. “I might be able to help, Eve, and you could do me a considerable service in return.”

Now she studied a lilac bush about a week away from blooming. First emotions of love.

“You already rendered me a considerable service, Lucas.” She spoke very quietly, and hunched in on herself, bracing her hands on the bench beneath them.

She’d called him Lucas. He’d been Lucas to the entire Windham family as a youth, and now he was Lucas to no one save Georgie. He wasn’t sure if he liked this presumption on Eve’s part, or resented it.

“I can have a word with Trit-Trot if you want me to run him off.”

She waved a hand. “I’ll mention the fact that I have only two dozen pairs of shoes, and the Season is soon upon us. In the alternative, I can suggest I’m never up before noon because I must have my drops every night without fail just to sleep. The tittering has slowed him down some, and if that doesn’t serve, I’ll turn up pious.”

So casual, and yet as she sat there on the bench, scuffing one slipper over the gravel, she was a battle-weary woman.

On impulse, he reached over and plucked her a yellow daffodil.

“What’s this?” She accepted the flower in a gloved hand, bringing it to her nose for a whiff.

Yellow daffodils for chivalry.

“You look in need of cheering up, but I see my offer was arrogant.”

“What offer was that?”

“I was going to assist you to assess the prospects of the various swains orbiting around you, and you were going to keep me informed regarding the ladies circling me.”

Now that he put the scheme into words, it sounded ungentlemanly, but Eve was not taking offense. She sat straighter and put the flower carefully to the side on the bench.

“You’ve been traveling off and on for the past few years,” she said. “This can put a man behindhand when in Polite Society.”

Egypt, the Americas, anywhere to escape his father and the man’s scathing tirades.

“I’ll be keeping to home territory for the foreseeable future, and you’re right: I have no idea who is overusing her laudanum, who owes far too much to the modistes, and whose mama plays too deep in unmentionable places.”

Now that he enumerated a few of them, the pitfalls for an unwary suitor seemed numerous and fraught.

Eve regarded her slippered toes. “Before the boys married, we used to gossip among ourselves terribly. They never told us everything, I’m sure, but they told us enough. We did the same for them, my sisters and I.”

And this was likely part of the reason no Windham son had been caught in any publicly compromising position, nor had any Windham daughters. And now the Windham infantry had been deserted by both cavalry and cannon.

While he had ever marched alone, which was a dangerous approach to any battle. “What do you know of the Staines ladies? They’re very determined, almost too determined.”

He asked the question because he genuinely wanted to know and had no one to ask whom he could trust. He also asked because he sensed—hoped, maybe—that Eve missed providing this sort of intelligence to her brothers.

“Lady Staines has a sister,” she said, dragging one toe through the gravel. “She chronically rusticates in Northumbria, but it’s said she’s quite high-strung.”

“Ah. And the daughter?”

Eve bit her lip then picked up her daffodil. “She did not make a come out until she was nineteen. Nobody knows precisely why, and Lady Staines does not permit the girl to socialize at all without her mama hovering almost literally at her elbow. We tend to feel sorry for Mildred, but she ignores all friendly overtures unless her mother approves them.”

And here he’d been half-considering offering for the girl just to trade the misery of the unknown for the misery of the known. He spent another half hour on that bench, listening to Eve Windham delicately indicate which young ladies might hold up well in a highly visible marriage, and which would not.

“Your recitation is unnerving, my lady.” In fact, what she’d had to say, and the fact that she was privy to so much unflattering information, left him daunted.

“Unnerved you in what regard?”

“I would never have suspected these polite, graceful young darlings of society are coping with everything from violent papas, to brothers who leave bastards all over the shire, to high-strung aunts. It puts a rather bleak face on what I thought was an empty social whirl.”

She did not argue. She sniffed her little daffodil. “Has this been helpful?”

She was entitled to extract her pound of flesh, so he was honest, up to a point. “You have been extremely helpful, and to show my gratitude, will you come with me to Surrey next week to make King William’s acquaintance?”

He put it purposely in the posture of compensation for services rendered, as if that particular exchange was the only one they managed civilly.

Her brows rose while she batted her lips with the flower.

They were pretty lips, finely curved, a luscious pink that put him in mind of a ripe—

The spring air was obviously affecting his male humors.

“I will come with you, provided you’re willing to take Jenny and Louisa as well, if Kesmore can spare her. They’d enjoy such an outing, and I’m sure King William would enjoy the company.”

“We have an appointment, then.”

He rose and bowed over her gloved hand, feeling a vague discontent with their exchange. As he made his way back out to the street, he turned and gave her a wave. She waved back, but the sight of her there on the bench, clutching her lone flower, left a queer ache in his chest.

Thank God, she wasn’t his type. He liked women with dramatic coloring and dramatic passions. Women with whom a man always knew exactly where he stood, and how much the trinket would cost that would allow him to stand a great deal closer.

But Eve Windham could talk horses, she was proving a sensible ally, and he did like to kiss her. She also drove a team like she was born to hold the reins.

What an odd combination of attributes.

“What did Deene say to Miss Georgina?”

Dolan kept his voice even when he wanted to thunder the question to the rafters. Miss Amy Ingraham was not a timid soul, but neither did she deserve bullying. She stood before him on the other side of his massive desk, back straight as a pike, expression that particular cross between blank and deferential only a lady fallen on hard times could evidence to her employer.

“His lordship said very little, sir. He played catch with the child and introduced her to Lady Eve Windham.”

Windham?

“One of Moreland’s girls?” The duchess herself would have been “Her Grace”—never “lady” this or that. Dolan knew that much, though the entire order of precedence with its rules of address left an Irish stonemason’s son ready to kick something repeatedly.

“I believe Lady Eve is the youngest, sir.”

This was the value of employing a genteel sort of English governess, granddaughter of a viscount, no less. She’d stay up late on summer nights and pore over Debrett’s by the meager light of her oil lamp, and she’d recall exactly which family whelped which titled pups.

“How young is this Lady Eve?”

“She’s been out several years, sir, from what I understand.”

“Did she say anything to Georgina?”

Miss Ingraham took a substantial breath, which drew attention to her feminine attributes. The day he’d hired her, Dolan had noted the woman had a good figure to go with her pretty face and pale blond hair. He knew of no rule that said governesses couldn’t be lovely for their employers to behold, though knowing the English, such a rule no doubt existed.

“Her ladyship complimented Miss Georgina on her curtsy, praised the dog, chided his lordship for throwing the ball too high, and thanked Miss Georgina for giving the horses a chance to rest.”

Lady Eve had chided his lordship. Dolan gave the lady a grudging mental nod, duke’s daughter or not. Deene was in need of a good deal of chiding, though he was no worse than the rest of his arrogant, presuming…

“Was there something more, Miss Ingraham?”

If anything, her spine got straighter.

“Speak plainly, woman. I don’t punish my employees for being honest, though I take a dim view of dishonesty.”

“Miss Georgina seemed to enjoy her uncle’s company very much, as well as that of Lady Eve.”

He peered at Miss Ingraham a little more closely. She had fine gray eyes that were aimed directly at him, and a wide, generous mouth held in a flat, disapproving line.

“How much do I pay you, Miss Ingraham?”

She named a figure that would have kept Dolan’s entire family of twelve in potatoes for a year, which was more a measure of their poverty than the generosity of her salary.

“Effective today, your salary is doubled. Start taking Miss Georgina to St. James’s Park for her outings. That will be all.”

“Are you attending one of Papa’s political meetings, or did Anna shoo you out from underfoot?”

Gayle Windham, the Earl of Westhaven, smiled at his sister’s blunt question.

“Hello to you as well, Louisa.” He passed the reins of his horse off to a groom and glanced from Jenny to Louisa. “You two are up to something.”

Standing there arm in arm, the flower of genteel English womanhood, they exchanged a sororal look. That look spoke volumes, about who would say what to whom, in what order, and how the other sister would respond. Westhaven’s sisters had been exchanging such looks as long as he could recall, and he still had no insight into their specific meanings.

His only consolation was that Maggie had once admitted there were fraternal looks that caused the same degree of consternation among the distaff.

“Walk with us.” Jenny slipped an arm through his, while Louisa strode along on his other side, a two-sister press gang intent on dragooning him into the mansion’s back gardens.

“Don’t mind if I do. I trust all is well with both of you?”

Jenny smiled at him, her usual gentle smile, which did not fool Westhaven for one moment. Genevieve Windham got away with a great deal on the strength of her unassuming demeanor, almost as much as Louisa got away with on the basis of sheer brass. He kept his peace, though. They’d reveal whatever mischief they were up to when they jolly well pleased to—and wheedling never worked anyway.

“What do we know of Lucas Denning’s marital prospects?” Louisa fired her broadside without warning.

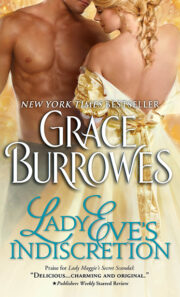

"Lady Eve’s Indiscretion" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady Eve’s Indiscretion". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady Eve’s Indiscretion" друзьям в соцсетях.